Zine Workshop

By Sean Hamilton + Ashley Stone

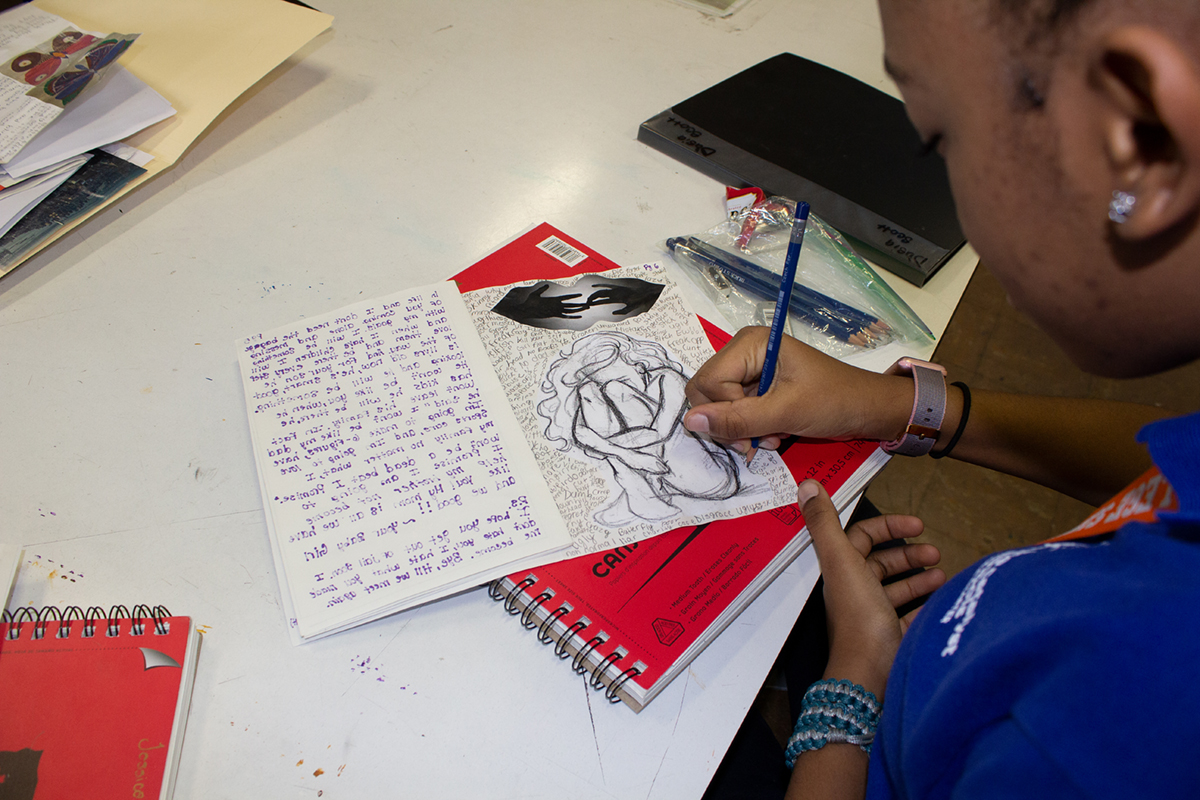

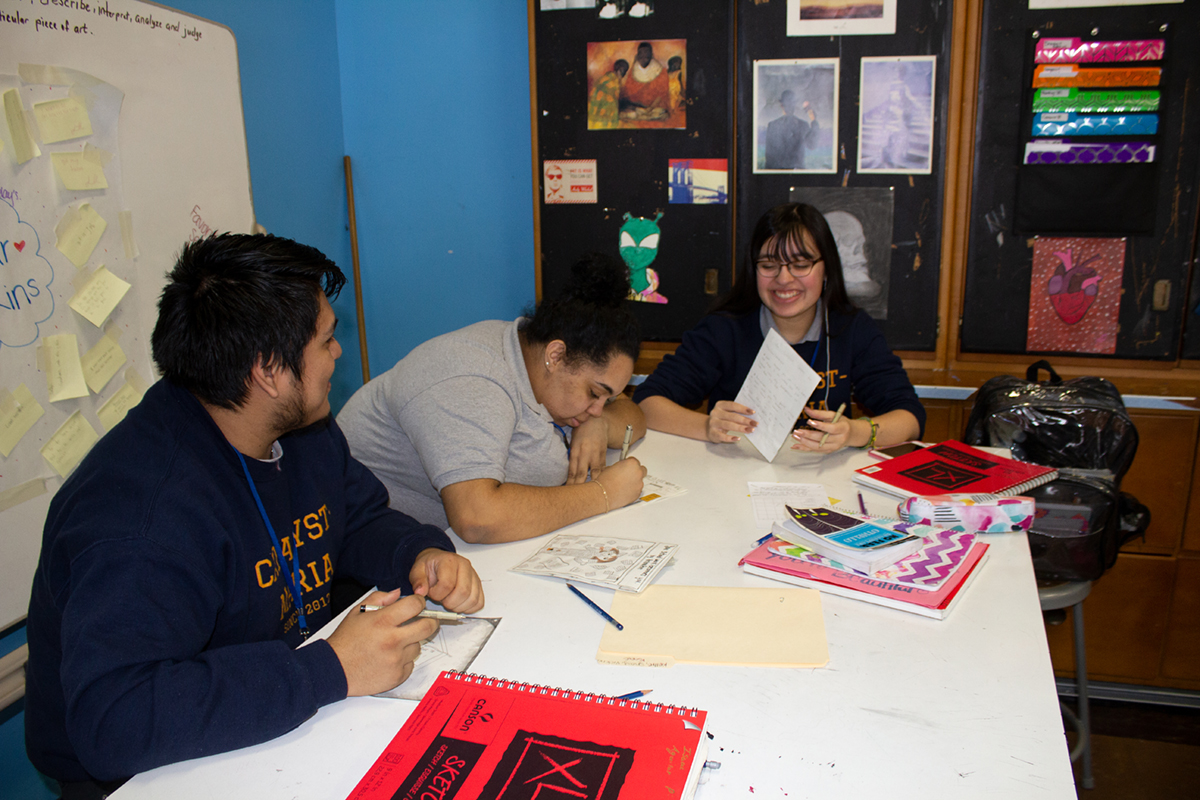

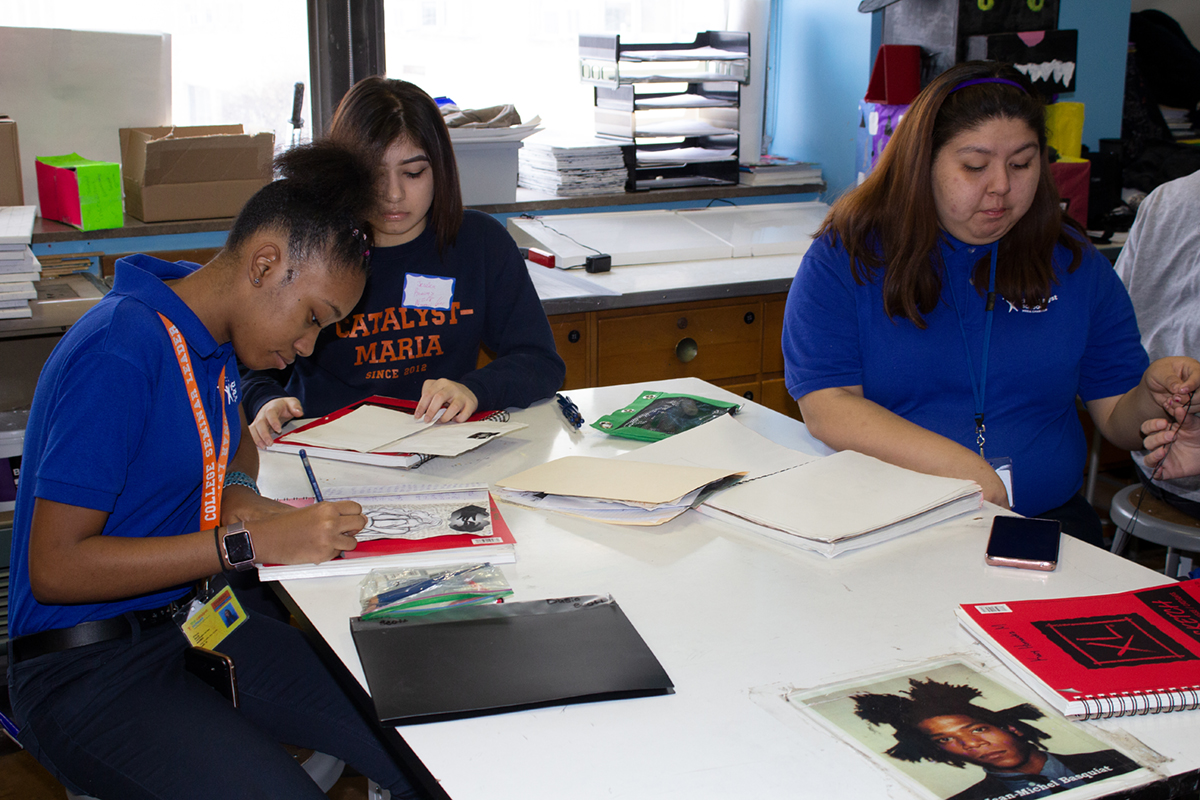

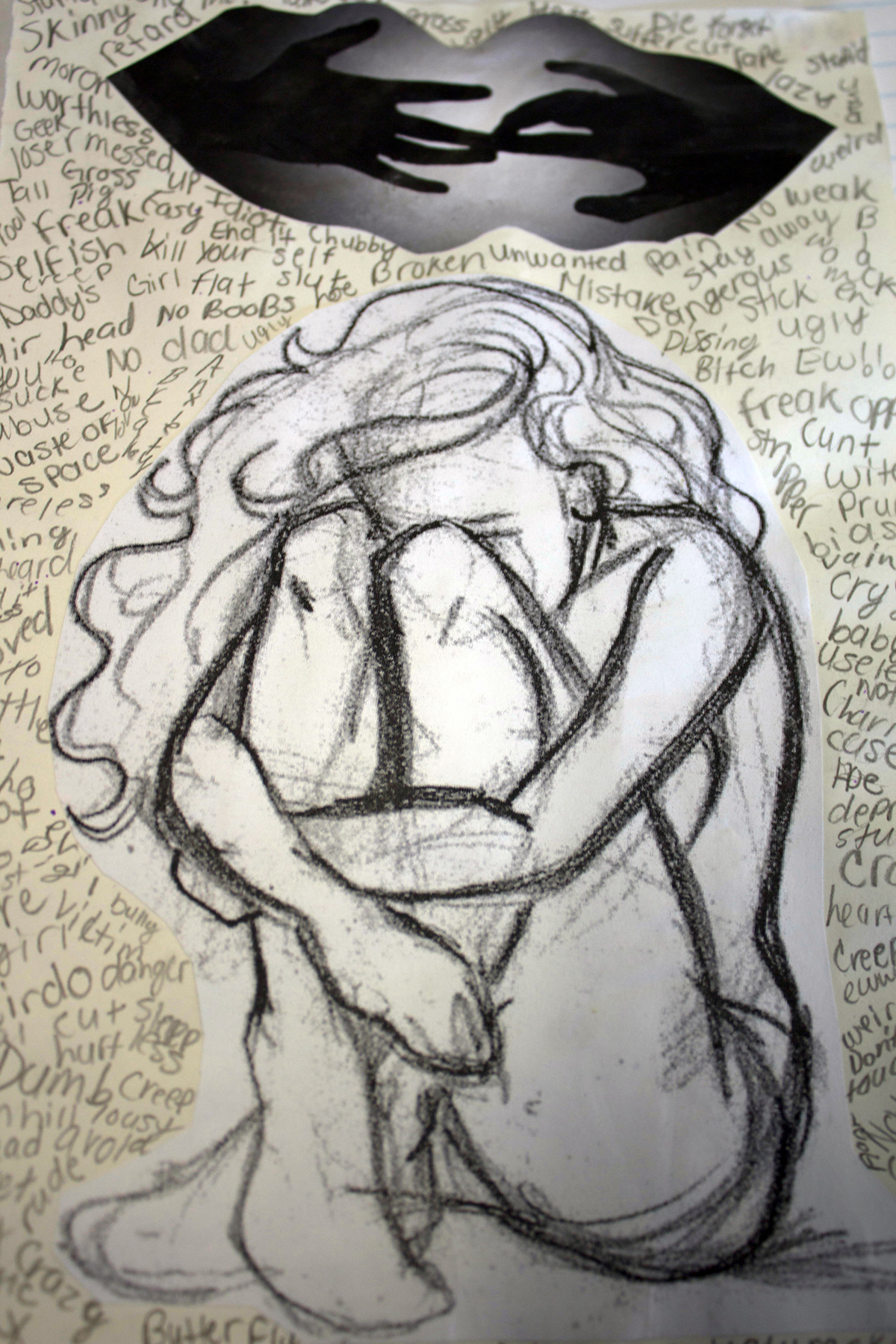

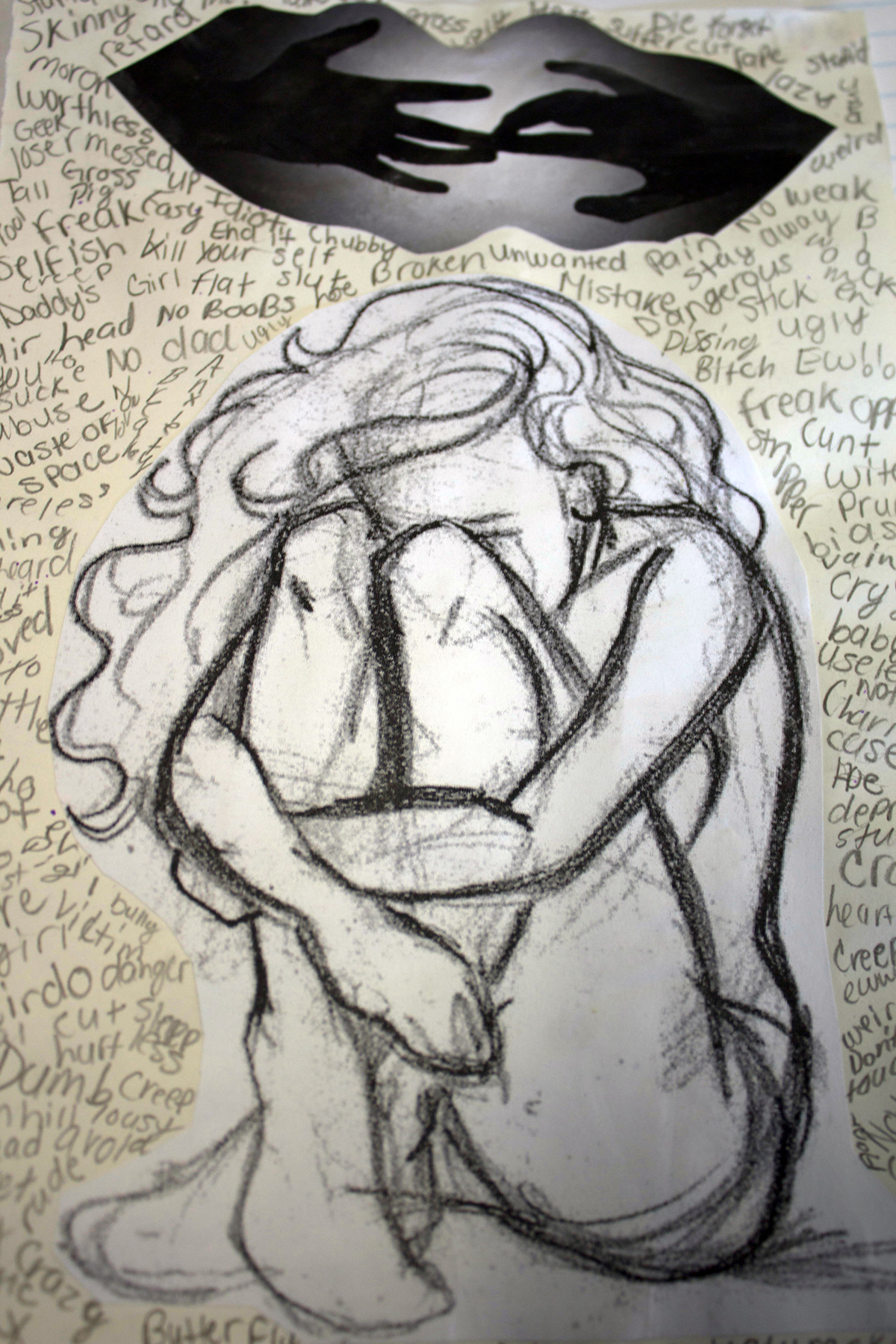

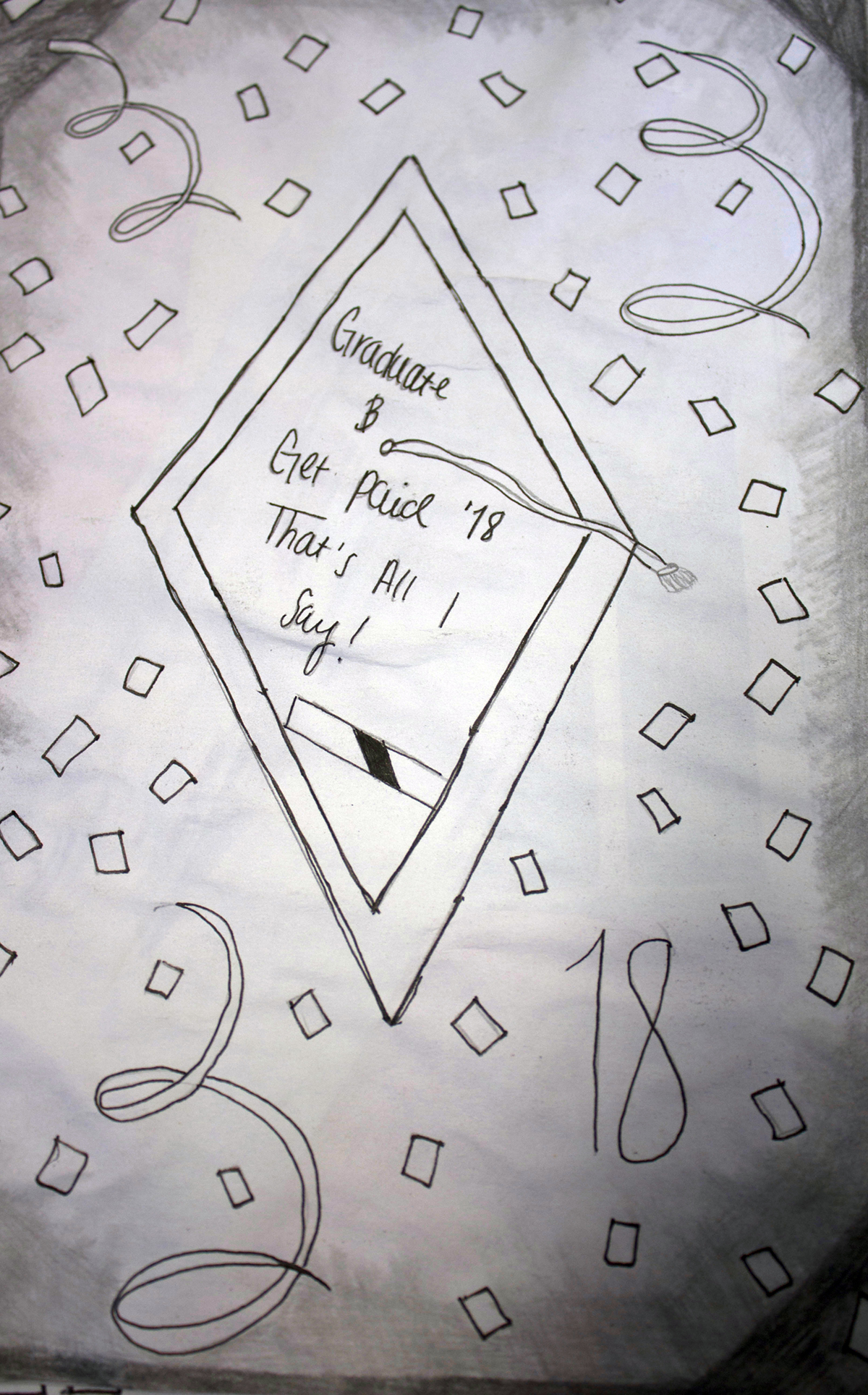

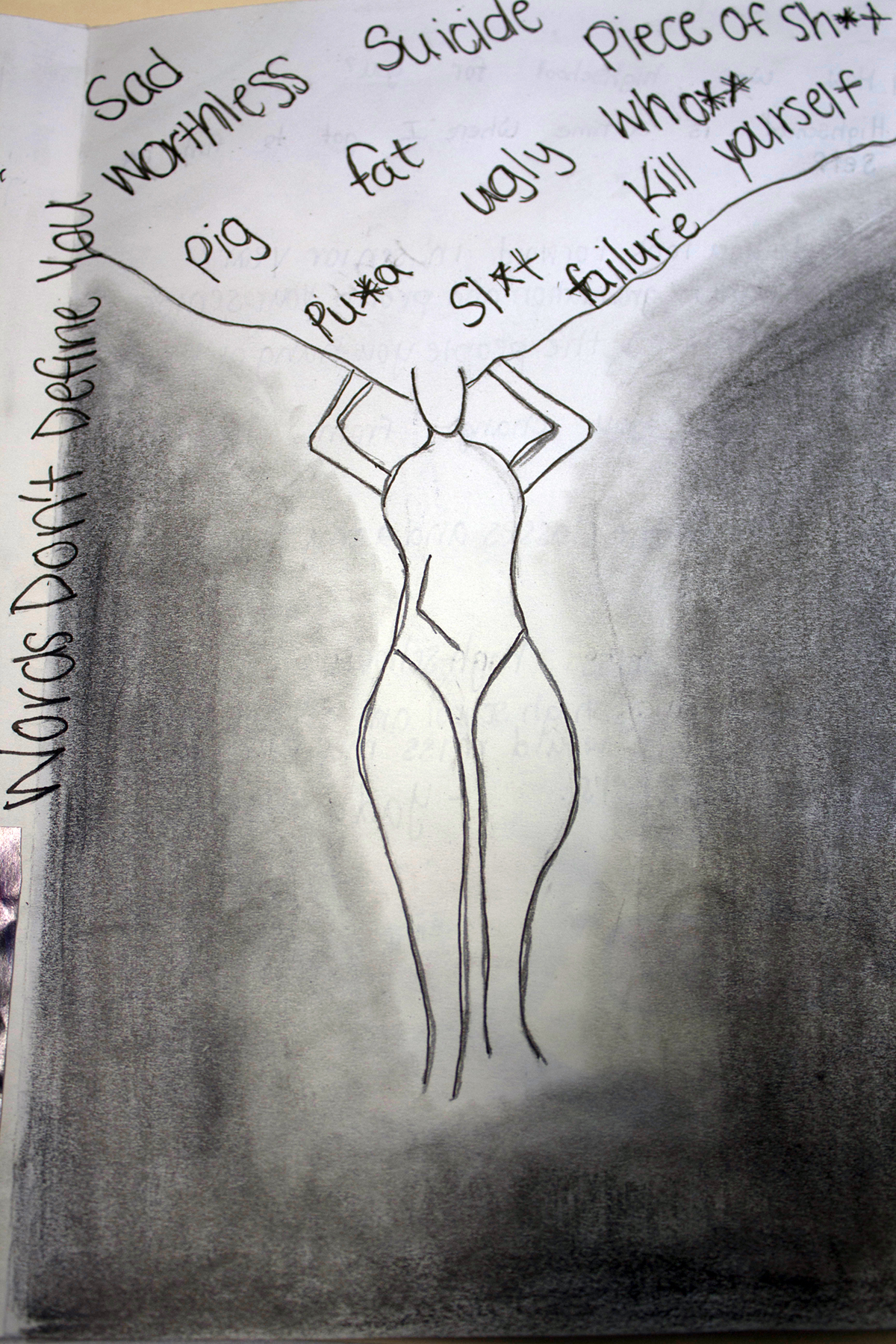

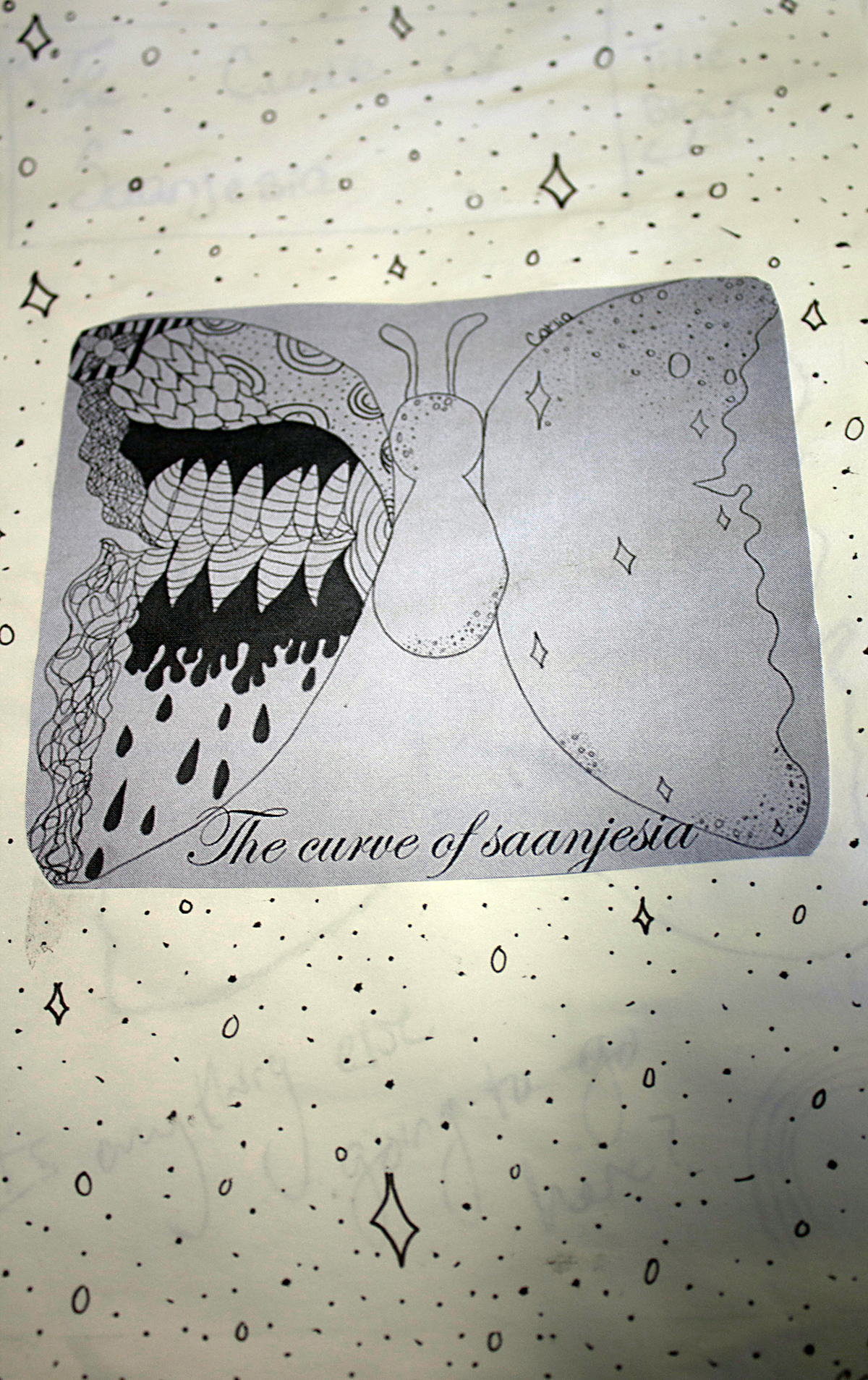

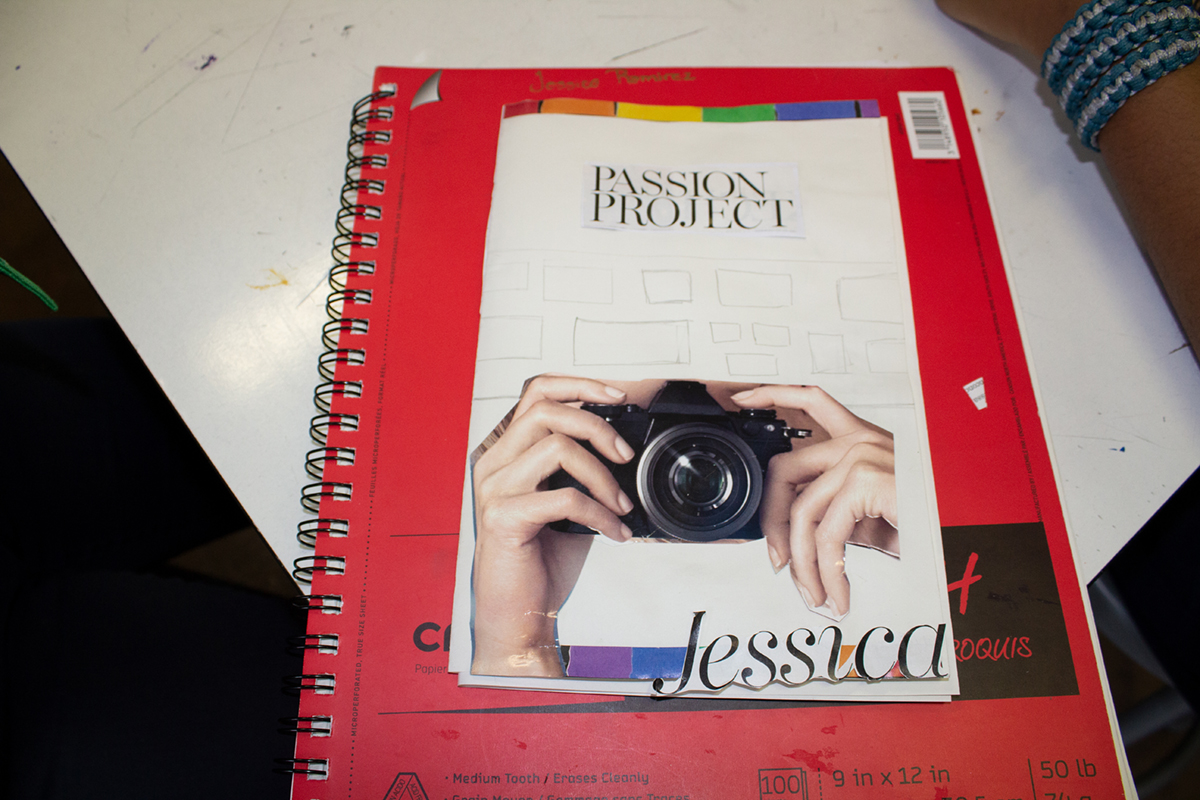

Students in a Drawing & Painting I course, in 10th–12th grades, collaboratively explored different facets and understandings of community through art-making. Our diverse school is located on the southwest side of Chicago, and for many of our students this is the first and last art course of their K–12 schooling. Students collaborated in small groups to create zines about specific communities in Chicago. Some of the most compelling successes of this process include a zine in which a student writes a letter to her absent father, a queer culture zine, and an African American hair care and history zine. During the process, students included additional contributions to the zines from other students outside of their classes and applied ideas and art-making methods they had learned prior, like zentangles, in order to fill their zine with visual content. The project culminated in the distribution of students’ completed zines within the school and into surrounding community businesses and organizations. The project challenges participants, students, viewers, and stakeholders to question the nature of community, its makeup, and the role of values and differences among various communities.

Goals

- Students will explore and critique previously published and independently made zines.

- Students will work with a group to create a zine that conveys ideas about community and values.

- Students will engage in research of various local communities.

- Students will participate in assembling an aesthetically engaging and informative zine for diverse audiences.

Questions

- How can we, as artists, express our values and those things we hold dear within communities both alike and unlike our own?

- What influences the construction of values within demographics, zip codes, and individuals, and how can these values be communicated to others within and outside of our communities?

- Is it possible to spread ‘values’ to others? Is it ethical to do so?

- What potential obstacles might be present in sharing personal values with diverse communities?

Documentation + Assessment Strategies

Students used writing, photography, and the construction of their own visuals to document and reflect on their ideas throughout the project.

The project itself serves as a form of collective documentation for each group of students. As a class, we also kept an organized folder of elements of the process that did not make it into students’ final zines, such as their brainstorming drafts, sketches, design proposals, and discussion notes.

The success of the project was assessed in a variety of ways. Students had to meet certain criteria on a checklist, including a set number of pages, enticing cover page, aesthetic appeal, inclusion of other voices, aim and scope of addressing the topic, and community research. Students were also assessed on the presentations and critiques of their zines.

Learning Activities

Timeframe

Students worked within their small groups twice a week for the duration of the construction of their zines. It took our classes about four weeks to complete their zines.

SETTING THE STAGE

Our original project was designed to integrate the arts into a general education course within our school. During this implementation, we experienced several obstacles, including administrative shifts and staffing dilemmas, that significantly altered, and in some cases completely changed, our project. After evaluating our options, the availability in our teaching schedules, and the present needs of our student community, we collaboratively created a Zine Workshop with a group of diverse students already enrolled in art. However, this process has implications for cross-curricular connections that can be implemented and explored in interdisciplinary teaching situations.

STEP 1

Visit the MCA

Artist Guides lead students in inquiry-based dialogue about Amanda Williams’s socially-engaged artwork. Throughout the project, students and teachers reference Williams’s work extensively as an access point into thinking about creation, working as a team, communicating ideas, and considering aspects of community and value.

STEP 2

Selection of and Orientation to Groupings

Organize students into groups for discussions designed to allow them to get to know more about each other’s understandings of community. Students share potential themes, ideas, and concepts they find personally interesting, relevant, and meaningful.

STEP 3

What is a Zine?

Introduce students to the purpose, rationale, and methodology of zines (small, portable, handmade books). Through discussion and videos, expose students to the idea and process of zine-making. Lead students in dialogue about issues that are significant in their lives and communities, in an effort to determine broad yet personal ideas worth exploring through the creation of a zine. Collaboratively determine clear guidelines for the project, in terms of format and content. Each group will create a sixteen-page zine, 8.5x5.5 inches in size (a total of four 8.5x11 sheets front and back). The zine requires each student’s contribution, and students will also include two additional contributions from students or other individuals outside of our classroom.

STEP 4

Zine Discovery

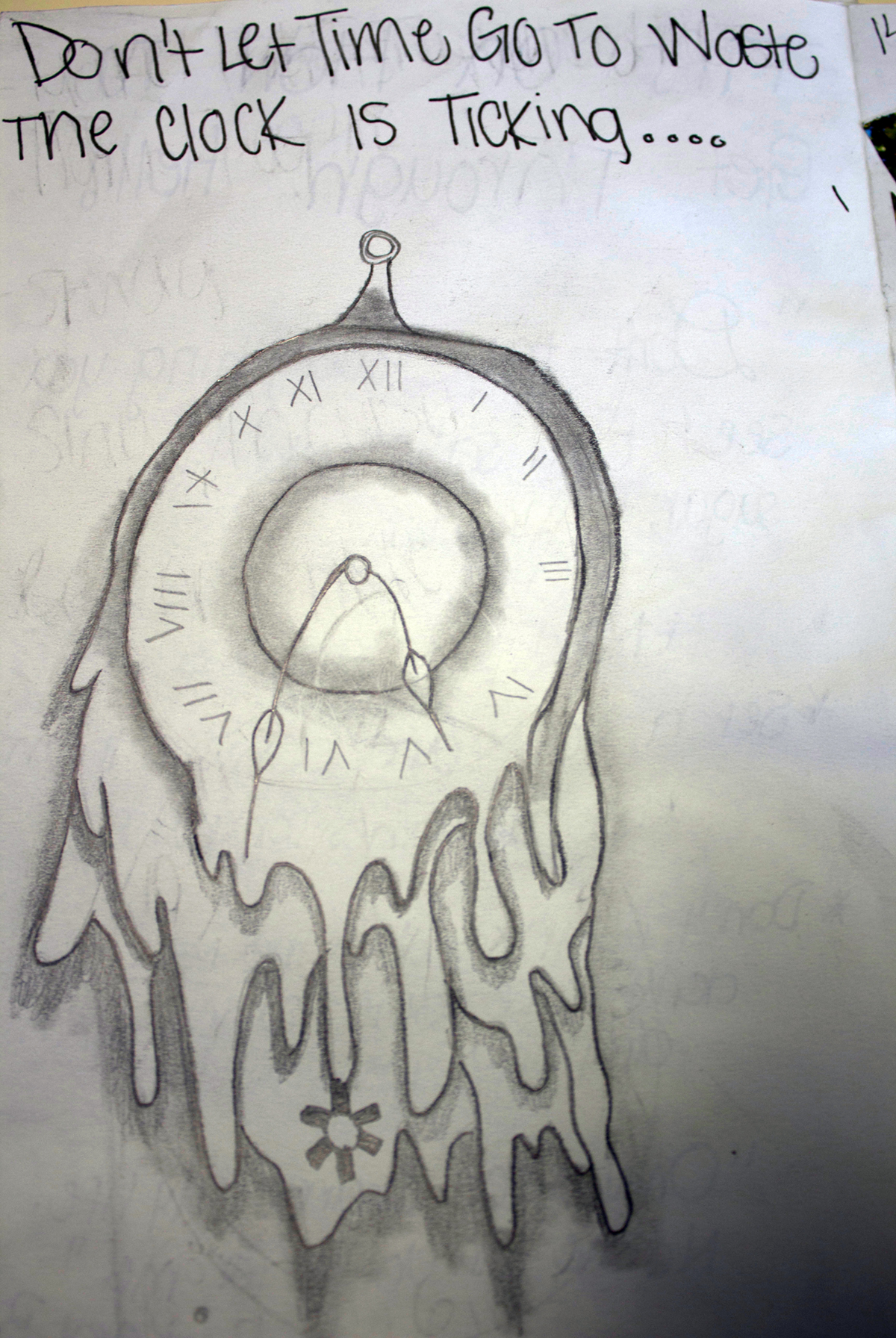

For many students, the concept of zines is foreign. Students spend time reviewing zines from various eras and authors/artists that represent different viewpoints and methodologies of creating zines. Some zines are graphic or visual in nature, some are text-based, and others demonstrate collaboration across disciplines and modalities—assemblage. Students complete a graphic organizer documenting themes and choices found in the zines.

STEP 5

Zine Critique

Students, who are already well-versed in critique, complete a short critique on zines in the form of a questionnaire to help guide their thinking about this format of conveying a message. Students use the critique questionnaire to review, interpret, and judge a zine created by their teacher.

STEP 6

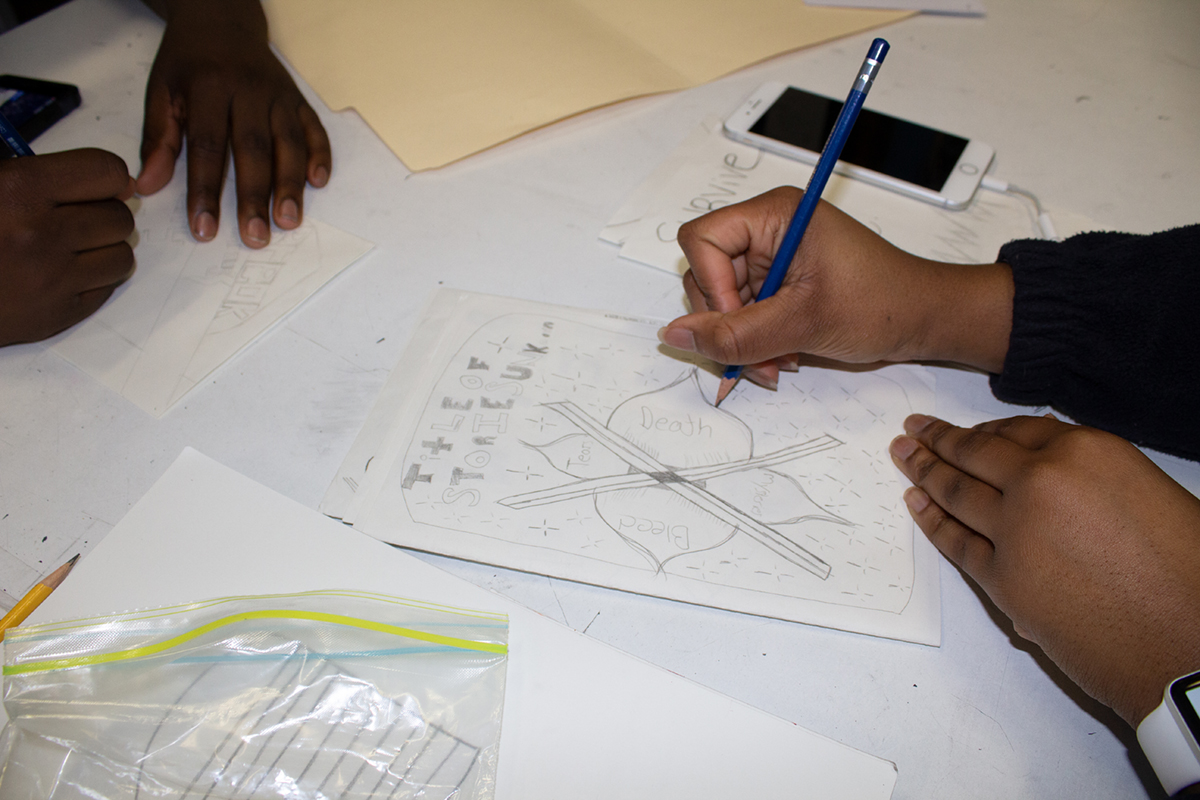

Zine Construction and Conferencing

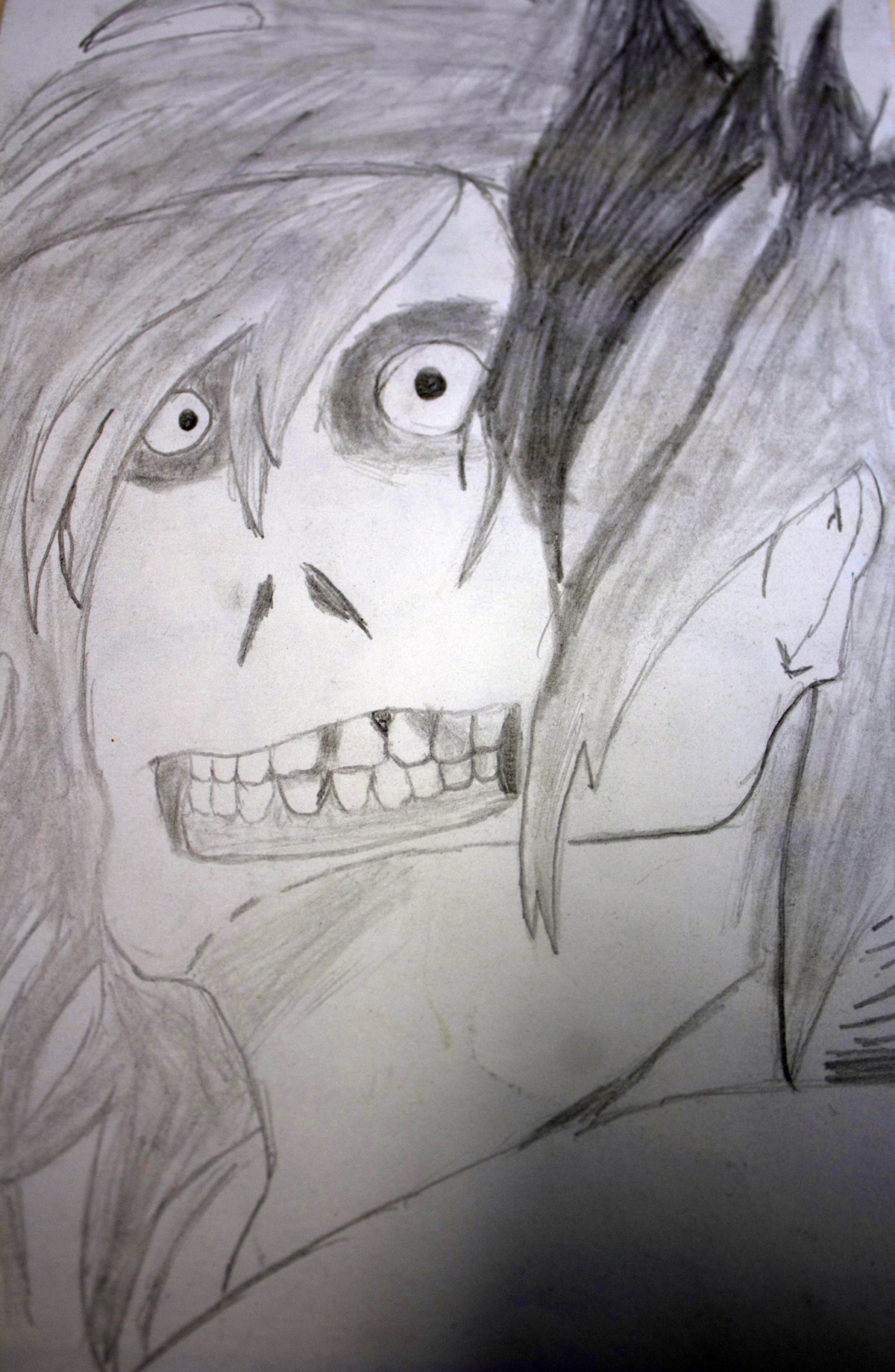

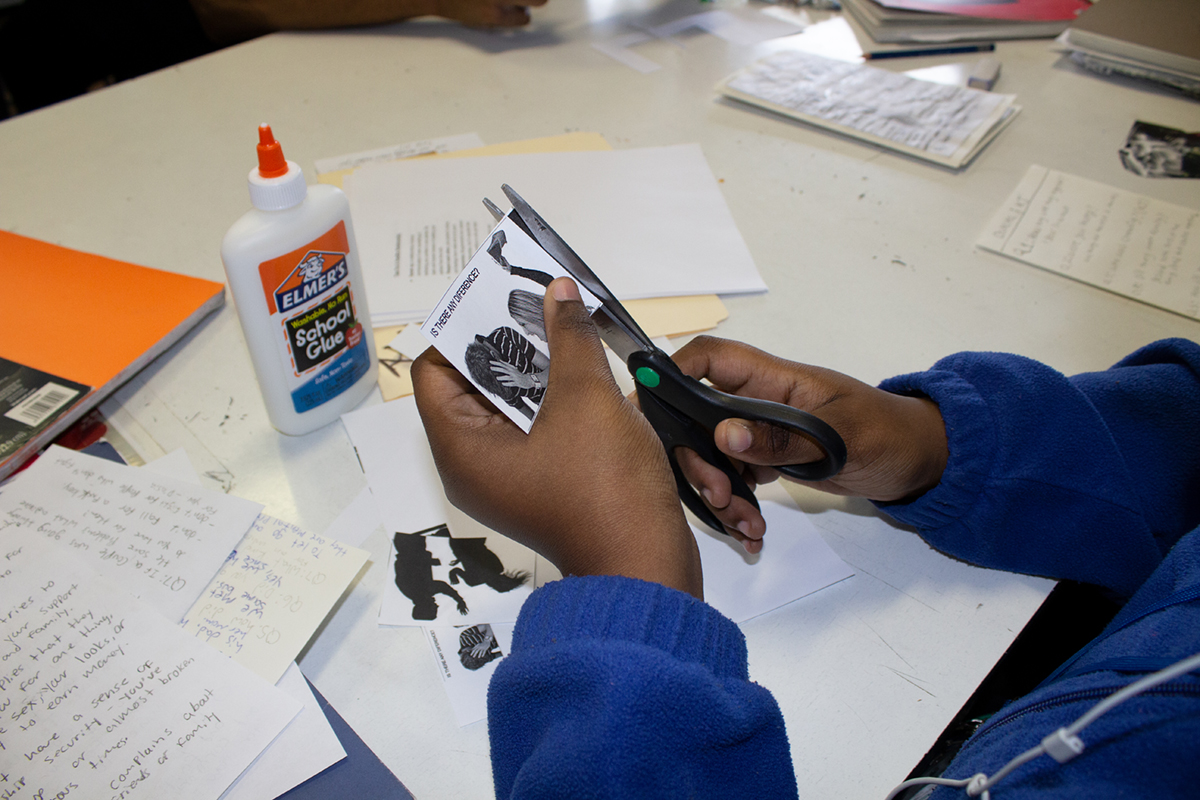

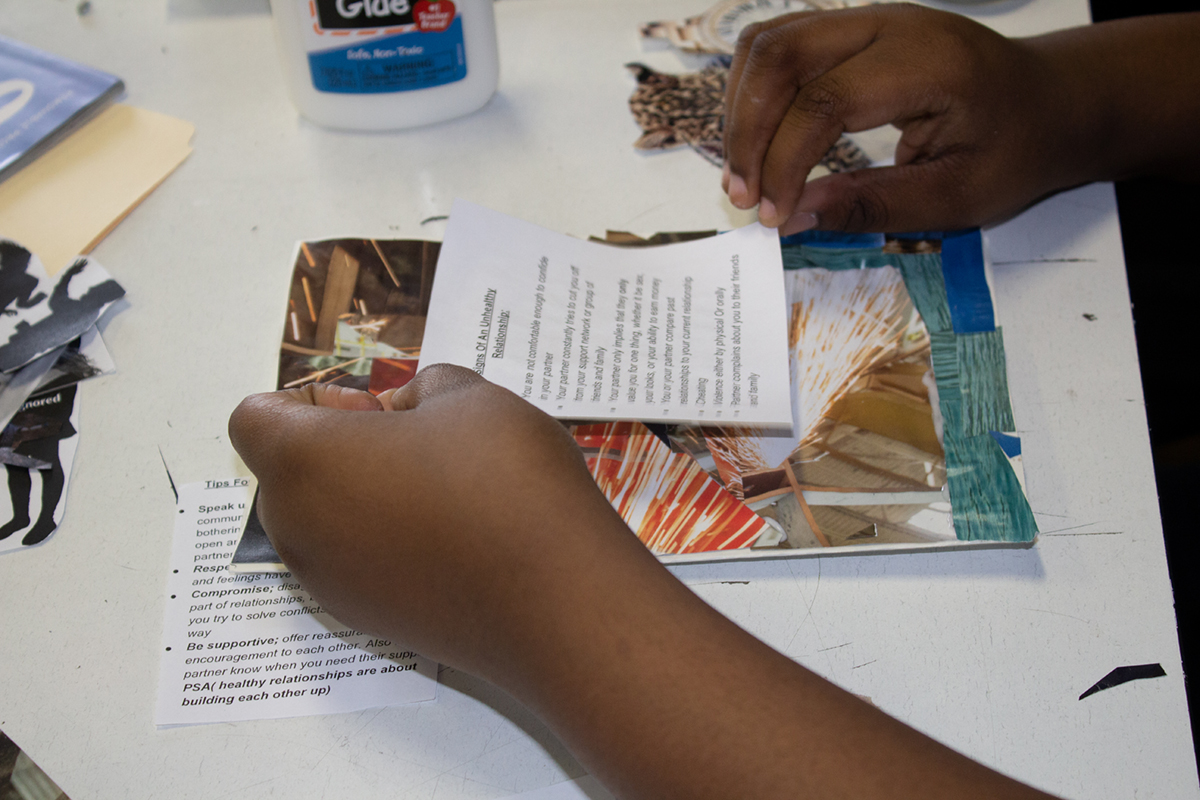

Students engage in cooperative mini-lessons on topics that can enhance their zine creation, including layout and spacing, copyright laws, fair-use policies, and bookbinding techniques. Students convey specific ideas about value and community, using a variety of the creative methods of making zines they learned about in Steps 3 and 4, including the use of collage, computer graphics, drawing, poetry, essays, surveys, and photographs. Students work in six small groups to create their zines in any format, utilizing any of the tools and materials within the room.

Teachers conduct regular conferences with each group throughout the construction phase, pushing conceptual thinking and encouraging students to expand on their creations through question-posing and peer dialogue. Students are tasked with finding two additions to their zine from sources outside of school—such as a drawings, photographs, quotes, interviews, etc. Teachers work with students to develop a vision for the zines designed for particular community audiences.

In this project, one student identified video games as his passion and was able to create a portion of his zine that reviewed recently released video games. Another group of graduating seniors created a zine that served as a guide for younger students to navigate high school.

STEP 7

Community Research

Students research various locations in specific communities that potentially align with the values and ideals set forth in their zines (or communities that may oppose those values). Students create proposals and write a rationale for why these locations are appropriate for the distribution of their zines, present this to the class for approval, and vote accordingly.

Most students choose the community they know best—their own. For many, their target audience is their peer group and friends, as students are excited to give copies of their zines to those they care about. Other students choose communities aligned specifically with their zine topic that might not be present in their local or current community. For example, one student in this project identified Boystown as a place to drop off her LGBTQ zine, and another group of students chose to drop off their illustrated zine to a local comic book store.

STEP 8

Photocopying!

Senior student interns provide the students instructions on photocopying and help them to mass produce their zines.

STEP 9

Distribution

This step includes two distributions. Students first distribute their zines internally, among the school community. Students then participate in a traveling distribution day in which they visit the locations they selected for distribution and make ‘drops’ at these locations. During this trip, students interact and engage with members of the communities they selected, documenting these interactions for a final presentation and celebration.

STEP 10

Final Presentation and Celebration

Students present their zines to their class peers and share their experiences during the creation, construction, and distribution of the zines, and during their interactions with the members of the communities they visited.

In this project, peers of the zine makers were generally most interested in the graphics presented within each zine. Zines that provided more text information were not as valued as those with more intricate visuals. The “Letter to my father” zine was the exception. This short letter written by a student to the father that left her family was read by the class and received positive critique.

Materials

- Glue

- Scissors

- Magazines

- Drawing and writing tools

- Paint

- Staplers

- Photography supplies

- Computers

- Paper

Students were permitted to use anything in our art space and bring items from home as well.

MCA Connections

During our trip to the MCA, students were able to view a wide variety of contemporary artworks and learn about the contexts of the artworks. The field trip served as a kickstarter for the project. Many of our students have not had the opportunity to interact with art, let alone contemporary art. The experience allowed students to consider their role in making art, how contemporary artworks convey specific messages, and how to discuss art and the artistic process. We used the field trip to position students as adventurers, asking them to document their own journey through the museum. Students were tasked with finding ‘out of bounds’ pieces that inspired them.

The discussions held at the museum exposed students to new ways of thinking about art and art-making. Amanda Williams’ exhibition was particularly inspiring as students were able to see the beauty and values of their community in accessible ways. Students also engaged with Michael Rakowitz’s work. In class, students were also able to critique and consider the work of Lee Bontecou in her assembly projects.

Sean Hamilton + Ashley Stone

Catalyst Maria High School

About Sean Hamilton

Originally from Philadelphia, Sean has been working with youth since early high school. Prior to relocating to Chicago in 2014 as a Teach for America Corps Member, Sean was the Art Education director at a local YMCA. Since then, Sean has worked teaching both high school American History and a variety of visual art courses in the Chicago Lawn neighborhood on Chicago’s southwest side. Sean focuses his teaching on creating unique and impactful art experiences that utilize the enrichment of guest speakers, college and museum visits, and using a variety of materials and approaches. At the end of the 2016–2017 school year, Sean spearheaded the school’s first STEAM Expo showcasing student work in the arts and sciences. In May 2016, Sean earned his Master of Education degree from Johns Hopkins. Sean is currently completing his first year in the Masters of Art Education at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

About Ashley Stone

As a Chicago native from the Morgan Park community, Ashley is an alumnus of Morgan Park High School. As a first-generation college student, Ashley attended the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. After graduating, Ashley began her teaching career as a 2011 Teach for America Corps Member, where she taught inclusion and sub-separate English at Chelsea High School in Chelsea, Massachusetts. While teaching in Chelsea, Ashley received the prestigious Sontag Prize in Urban Education Award and attended Boston University to pursue her Master of Education in Curriculum and Teaching. After teaching in Chelsea for two years, Ashley returned home to the Southside of Chicago to empower and inspire younger generations of color to achieve academic excellence.

Sean + Ashley Reflect on the Project

We encountered a number of setbacks during the implementation of this project. Originally planned as an art integration pilot, the project did not fit into the cooperating teachers’ curriculum, and we paused our originally intended project. We quickly went back to the drawing board and created a Zine Workshop, different from the typical Drawing curriculum, that allowed a group of diverse learners to engage with concepts of community, identity, and communication. Along the way we had shifts in staff, student enrollment, and administration that made completing the project more of a challenge. Additionally, we did not realize the level of support necessary to help our students succeed in the creation of their zines. After some reflection we were able to adequately accommodate all students.

Nonetheless, the project was completed with some adjustments. We were unable to take a class field trip to various locations for the zine drop due to finances, student interest, and time. We had hoped this would have been the culmination of the project. Working with students, we were able to orchestrate zine drops throughout our school and plan to have zine copies available at our STEAM Expo in May. Additionally, students who attend optional field trips hosted by our school have been able to drop their zines off at various locations along their route. Some students, for example the student who created the LGBTQ zine, traveled to specific neighborhoods to drop off their zines.

When students began participating in daily conferences with a teacher, we could see their vision and passion coming to life. It was clear that with some direction, support, and encouragement, our students were capable of making incredibly interesting and unique products. Over time, students were able to focus on a specific topic and/or community that they hoped to include in their zine-making. Some of the content students created posed ethical concerns, like the use of profanity, but were ultimately approved for use. We continued to work with students throughout the project, ensuring they were on track with regular conferencing and critiques of their work.