Creating Researchers, Writers, + Activists Through Art

By Abi Wilberding

Sixty students at CICS Northtown Academy in an 11th–12th grade writing course titled “Humanities: Art into Action,” used writing and art to become active researchers and potential activists. Using journals as tools for developing and adjusting their own primary resources throughout the semester, students engaged in a variety of activities. Students first developed a broad but personal research question by examining their passions and the passions of others. Students were then exposed to a diverse array of artists, artworks, and field trip experiences that helped them to answer their question. At the end of the semester, students used their journals, now full of visual and written material, as evidence to support a persuasive paper and serve as the basis for an art project pitch in response their individual research question.

Goals

Through the creation of a journal, develop a primary source document for analysis, reflection, and research.

- Develop confidence and aptitude as an activist, researcher, and writer.

- Use art as a means of research exploration and evidence collection.

- Engage in meaningful out-of-class experiences in order to connect research to broader life contexts.

Guiding Questions

How can the development and collection of research become personal and powerful?

- How can we, as a class and as individuals, better identify ourselves as researchers and writers?

- What questions might artists be answering through their work?

- How can we use the world and our experiences outside the classroom as a text for our research?

- How do artists address issues of value in their communities through research and creating artworks?

Documentation + Assessment Strategies

Students used journals to document this entire experience. Each student had a hardbound journal documenting their journey through research, exploring their passion, and creating art. Students used their journals to analyze their own lives and what matters to them over the course of this project.

Photographs to document the semester-long experience were taken during key activities, including the concentric circle analysis, the Amanda Williams-inspired “Museum of Value,” and the visit to the MCA.

Throughout the semester, student-created rubrics were used on formative and summative research assessments. At the end of the semester, students collectively decided how to assess the socially engaged project proposals through a class discussion and consensus.

Learning Activities

Timeframe

This project took one semester to complete; however, it could be adjusted depending on time constraints. For instance, one aspect of this project (i.e. the “Museum of Value” inspired by Amanda Williams) could be used as an activity separately from the entire project, or journals could be used as research tools independently. View this project as a portfolio: Pick the activities and tools that work best for your classroom.

SETTING THE STAGE

How can the development and collection of research become personal and powerful?

The crux of this entire project is the tool used by all students: the journal. It is incredibly important to show excitement and even reverence for the journals before students use them. There are a few ways to do this.

Modeling: Teacher as Journaler (and Human)

Reflect: How have you used journals in the past? Why are journals important to you personally?

Modeling the importance of journaling requires vulnerability. Collect and share the journals you have created over time. If you do not have journals, what have you used to develop your craft? Share that and explain how you would adjust it for journaling. Place bookmarks in the portions of the journal that best model what you expect from student work. If comfortable, pass your journals around the room for student exploration while presenting your history of journaling/art-making.

The Handing Out of Journals: Graduation (to Becoming a Researcher)

Reflect: How can you create an event that activates student ownership and respect of journals?

Before class, write the name of each student on the side of the journals. At the front of the classroom, call students’ names one by one and hand their journal to them as if it is a diploma (handshake optional).

Giving Power: The First Entry

Reflect: How can students take ownership of their journal and find voice?

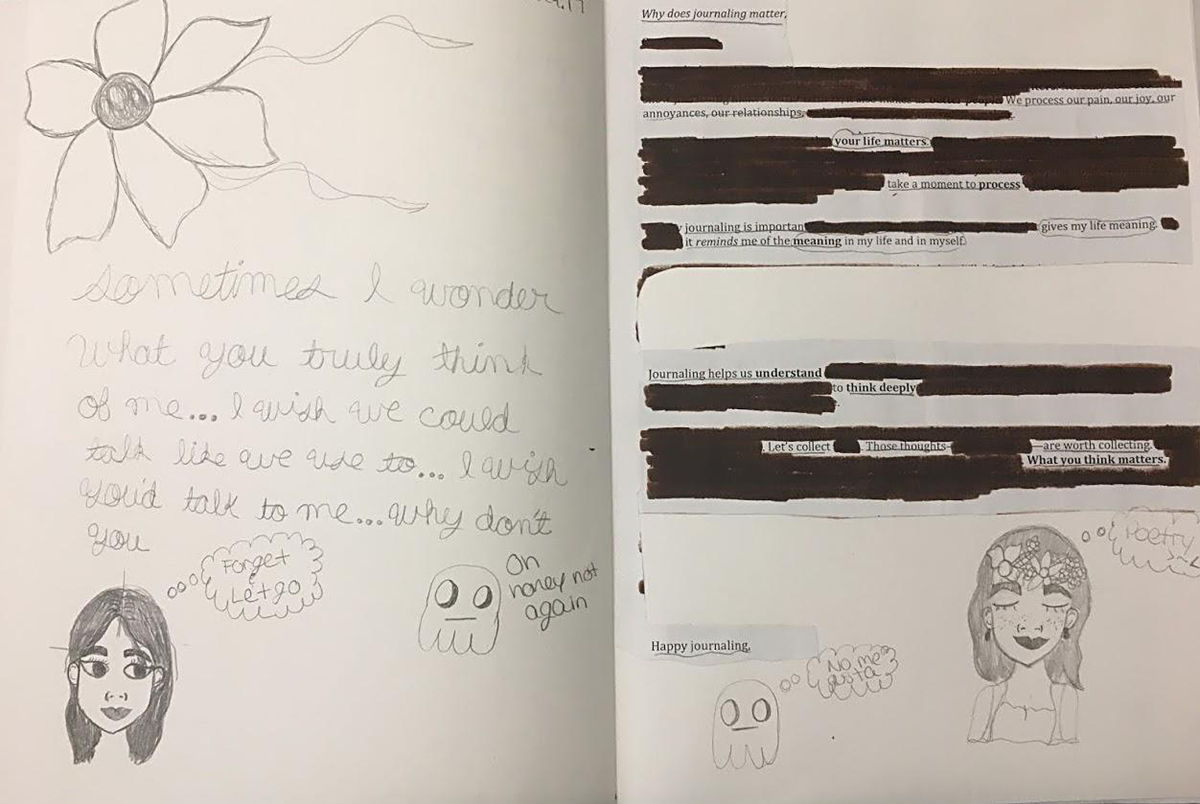

Before class, write a letter to the class about the importance of journaling and your hopes for them for the semester. Read this letter to the entire class. Explain the practice of blackout poetry (creating your own work from someone else’s by blacking out select words). Have students create their own personal blackout poems with your letter. Students should glue this blackout poem into their journal as the first entry.

Routine: Journals Everyday

Reflect: How can routines create a culture of professionalism and importance?

Consider having a place in the classroom where students keep their journals. Have a routine for how students access their journals everyday. Make sure students are using them consistently.

PART 1: PASSION DISCOVERY

How can we, as a class and as individuals, better identify ourselves as researchers and writers?

In order to become engaged in research, students must develop questions based on their own curiosity and previous life experience. Although students come to class with a wealth of interests, many students have difficulty accessing personal knowledge for academic purposes. Supporting students in rediscovering their passions as a means of researching and writing promotes students’ commitment to the semester research and connects their interests to a larger context.

Interviewing and Presenting the Passions of Community Members

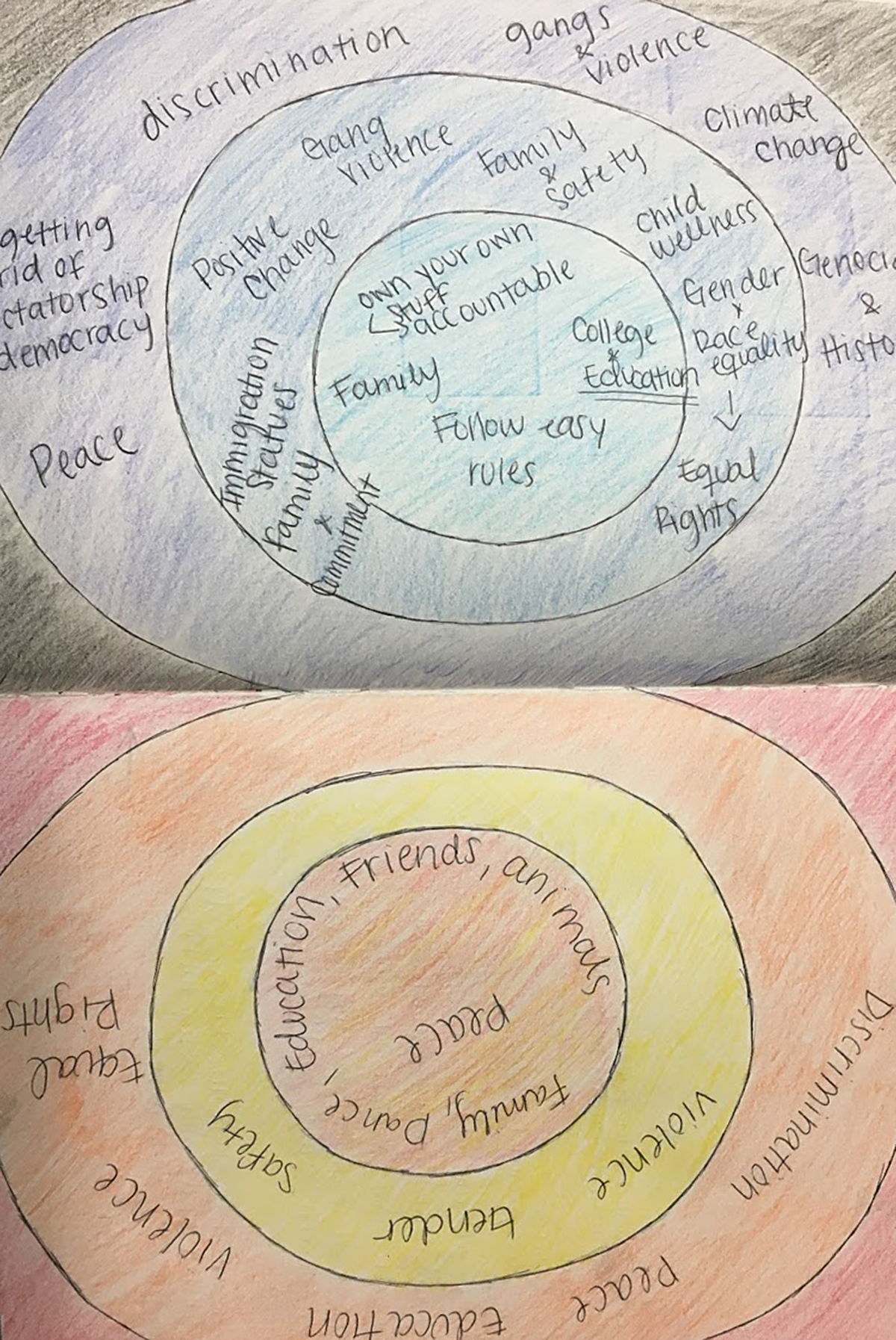

- Students choose a person to interview about their personal, local, and global passions.

- Students individually record their chosen person’s passions on a concentric circle map.

- Students present their findings and record the passions on a class concentric circle projected at the front of the room.

Developing a Semester Focus Research Question

Students choose a passion that interests them and develop a research question at the front of their journal.Teacher gives critique of research question and students revise research questions.

Sample Research Questions:

- Why does society consider a woman’s silence a norm and fear her voice?

- How can art inspire us to change?

- How can safe spaces be created to support diversity and identity?

- How can art be used to build empathy in others?

PART 2: ART EXPOSURE AND EVIDENCE COLLECTION

What questions might artists be answering through their work? How can we use the world and our experiences outside the classroom as texts for our research?

After identifying their passion, students collect evidence for answering their question through three means of experiencing art: art openers, analysis projects, and exploration with field trips. Students begin to build answers to their questions while also investigating models of socially-engaged art.

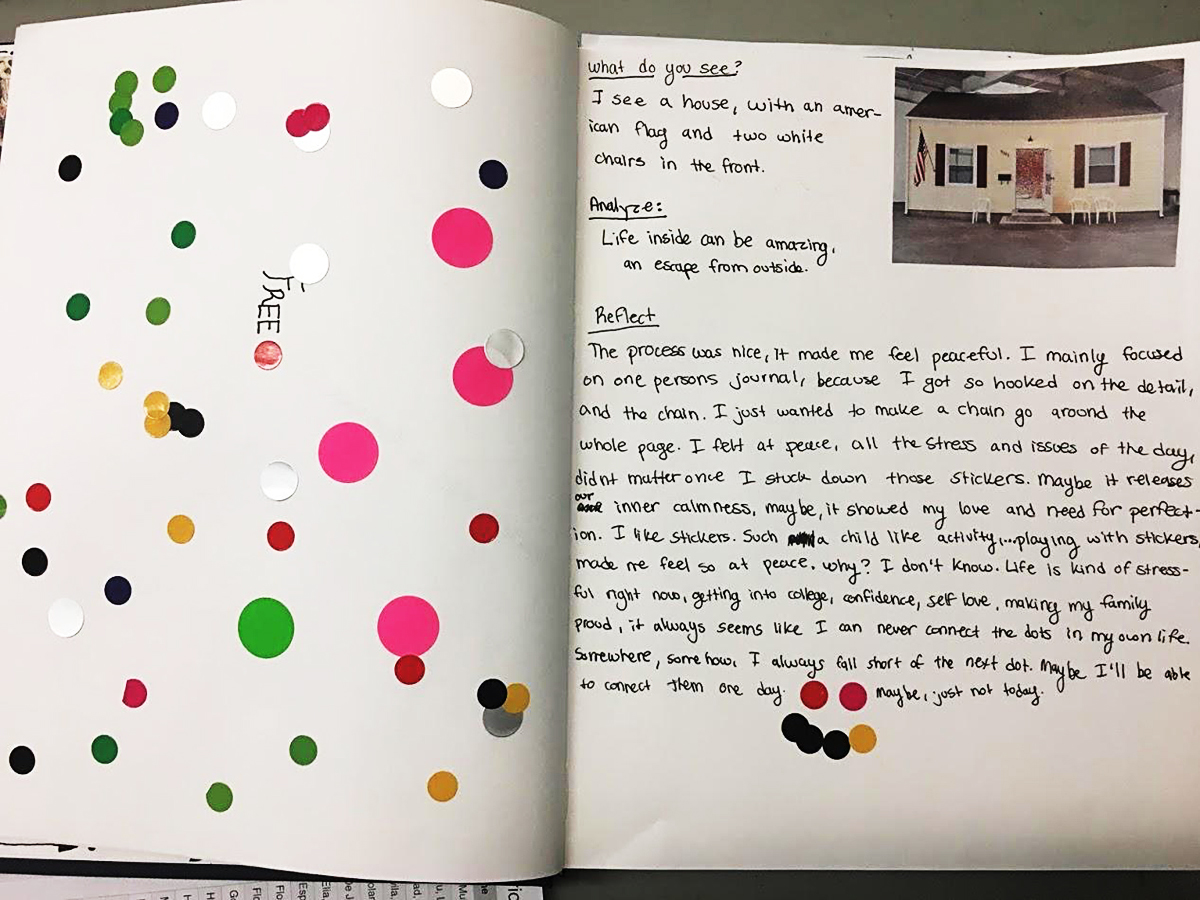

Art Openers: Everyday Visuals with See, Think, Wonder

Every day, as students enter the classroom, give them an image of an artwork to glue into their journal and analyze independently.

As a class, guide students through the image by asking:

- What do you see?

- What do you think?

- What do you wonder?

Students discuss each question in their small groups and then come back together to share and ask further questions.

Possible student prompts: What parts of this artwork connect to a theme or key term in your research question? How might this artist answer your research question? How can you connect previous experiences or other texts to this artwork and your research question?

PART 3: ANALYSIS PROJECTS

Art as Activism and Response to Social Issues

How do artists address issues of value in their communities through research and creating artworks?

Project 1: Murakami’s Arhats and the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami

- Visual Analysis: Students glue images into their journals and then use See, Think, Wonder as a tool to analyze Murakami’s 500 Arhats.

- Students individually brainstorm reasons Murakami might have created his arhats and share these reasons with the class.

- Artist Background: Students watch the video on Murakami’s background and his process for creating the 500 Arhats.

- Issue Background: Students watch The Phone of the Wind and collect quotes that connect to Murakami’s arhats.

- Class Discussion, Analysis & Journal Reflection: Students analyze and discuss how Murakami’s arhats respond to tragedy.

- Extension Questions: What would a Phone of the Wind look like at your school? How does Murakami’s art relate to your research question?

Project 2: Amanda Williams and Issues of Value

- Think/Pair/Share/Write: Students use the think, pair, share, write process in order to define value and determine what is most valuable in their lives.

- Visual Analysis: Students glue an image of Be the Girl with the Turned on Hair into their journals and then analyze the artwork using the See, Think, Wonder strategy.

- Caption Creation: After reading Williams’s caption for Be the Girl with the Turned on Hair, students discuss the difference between their personal understanding of value versus what society determines to be valuable.

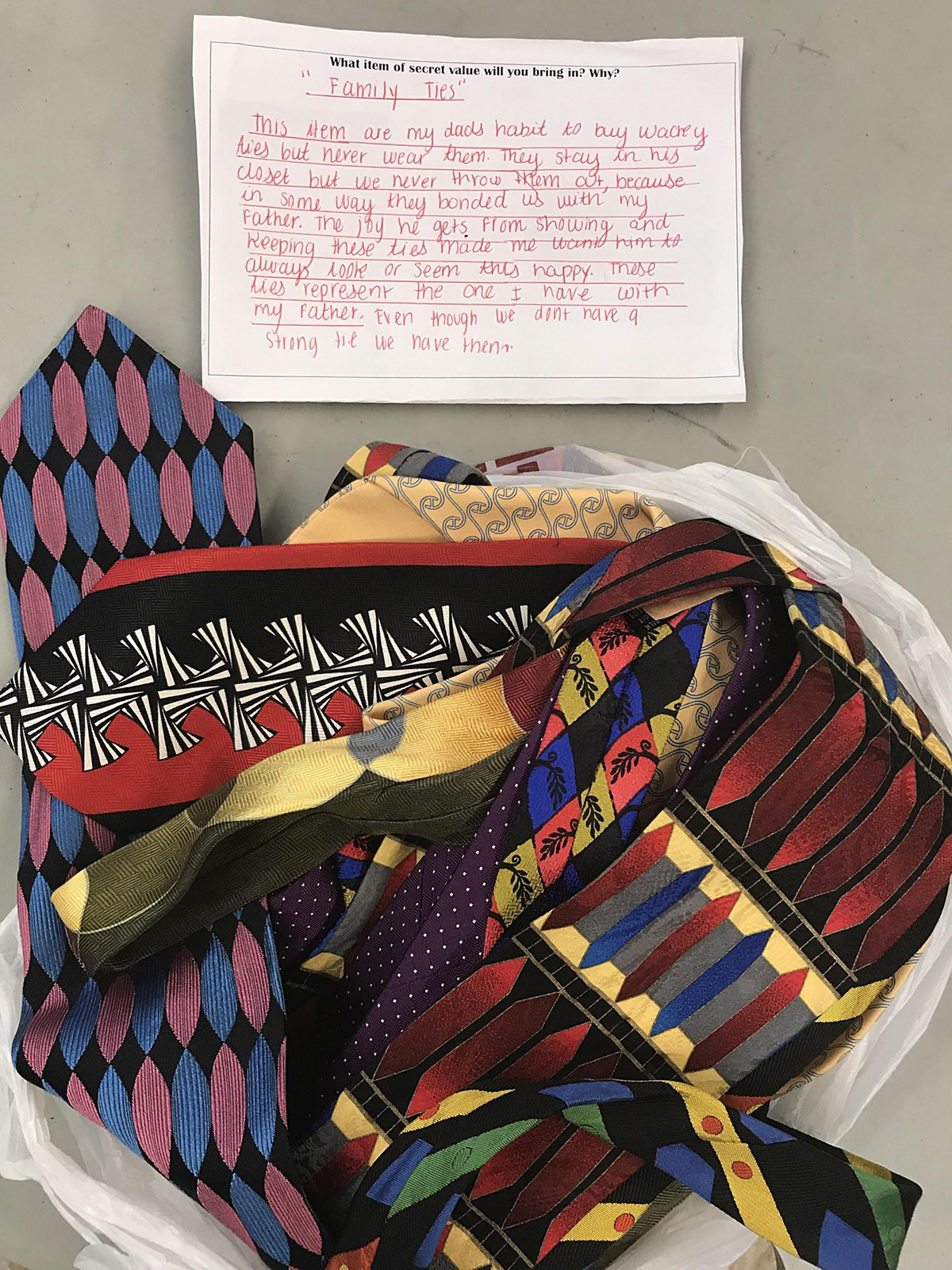

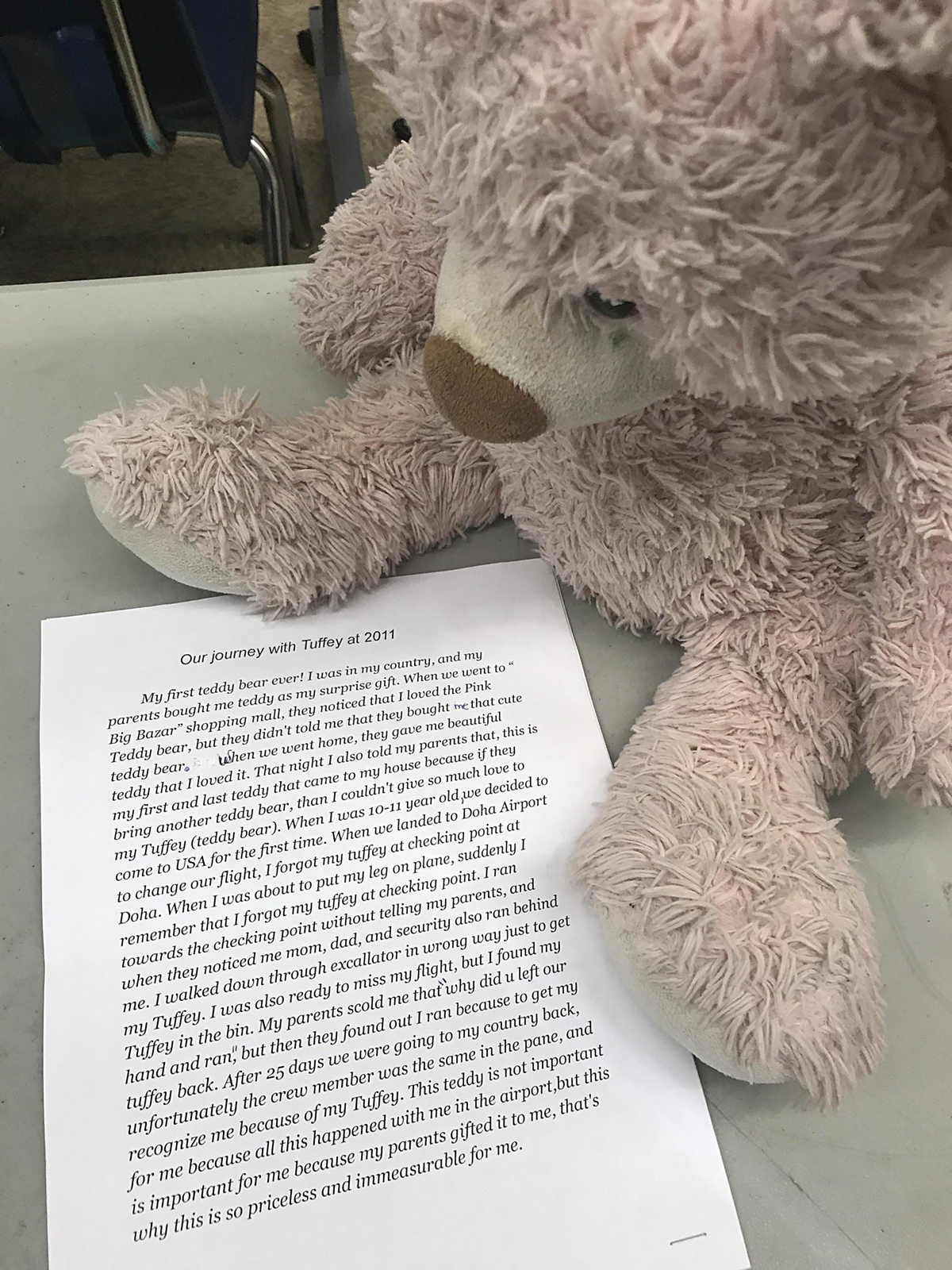

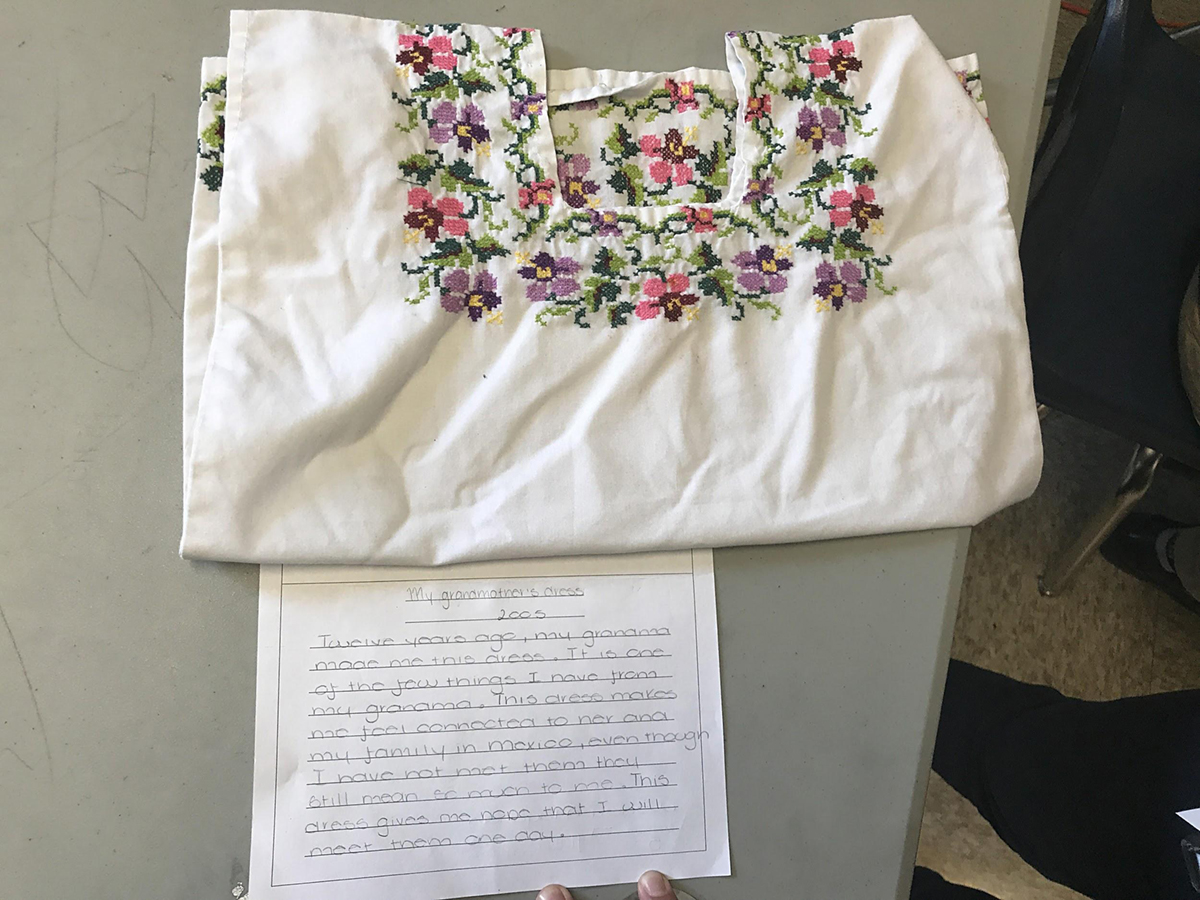

- Collecting Personal Objects of Value: Students choose an object that is personally valuable to them but might not be considered valuable to others. Students create a placard for their object with a title, year, and description.

- Museum of Value Curation: Students bring their objects into class and place them around the room with their placard face-down.

--> Round 1: Students walk around analyzing the objects based solely on physical appearance. Students collectively determine the five most valuable objects in the room.

--> Round 2: Students flip the placard face-up to tell the stories of the objects. Students read the placards for each class object and determine the five most valuable objects based on the descriptions. - Class Discussion, Analysis & Journal Reflection: After exploring their object museum, students analyze and discuss how Williams’s art changes our perspective on value.

- Extension Questions: How did our ideas of value change during the rounds? How does this change our understanding and definition of value? How does Williams’s work relate to your research question?

Project 3: Jan Tichy and the Poisoning of Flint Water

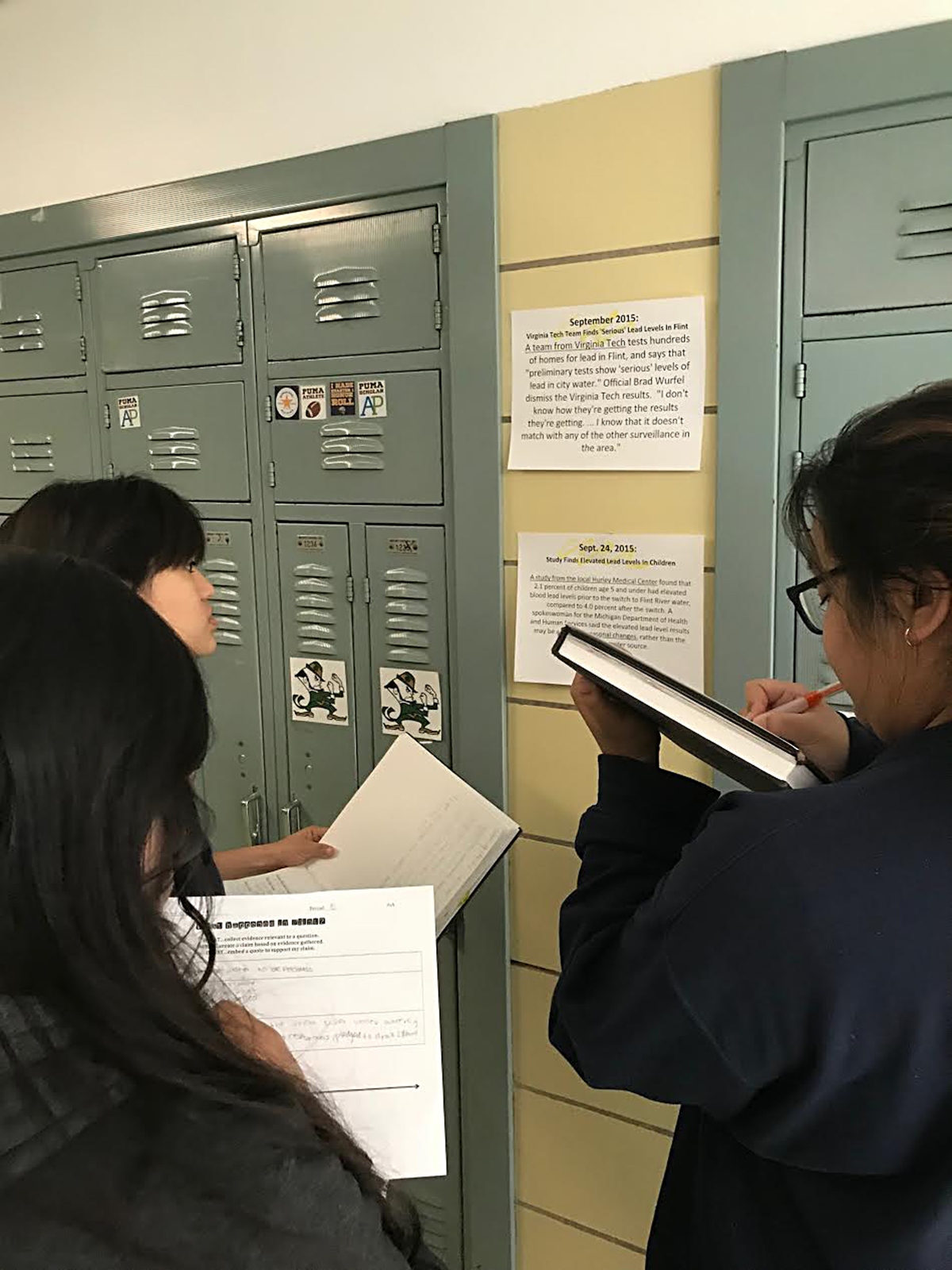

- Issue Background: Students analyze a video on the water crisis in Flint, Michigan: “Failing Flint: Who Knew What and When?”

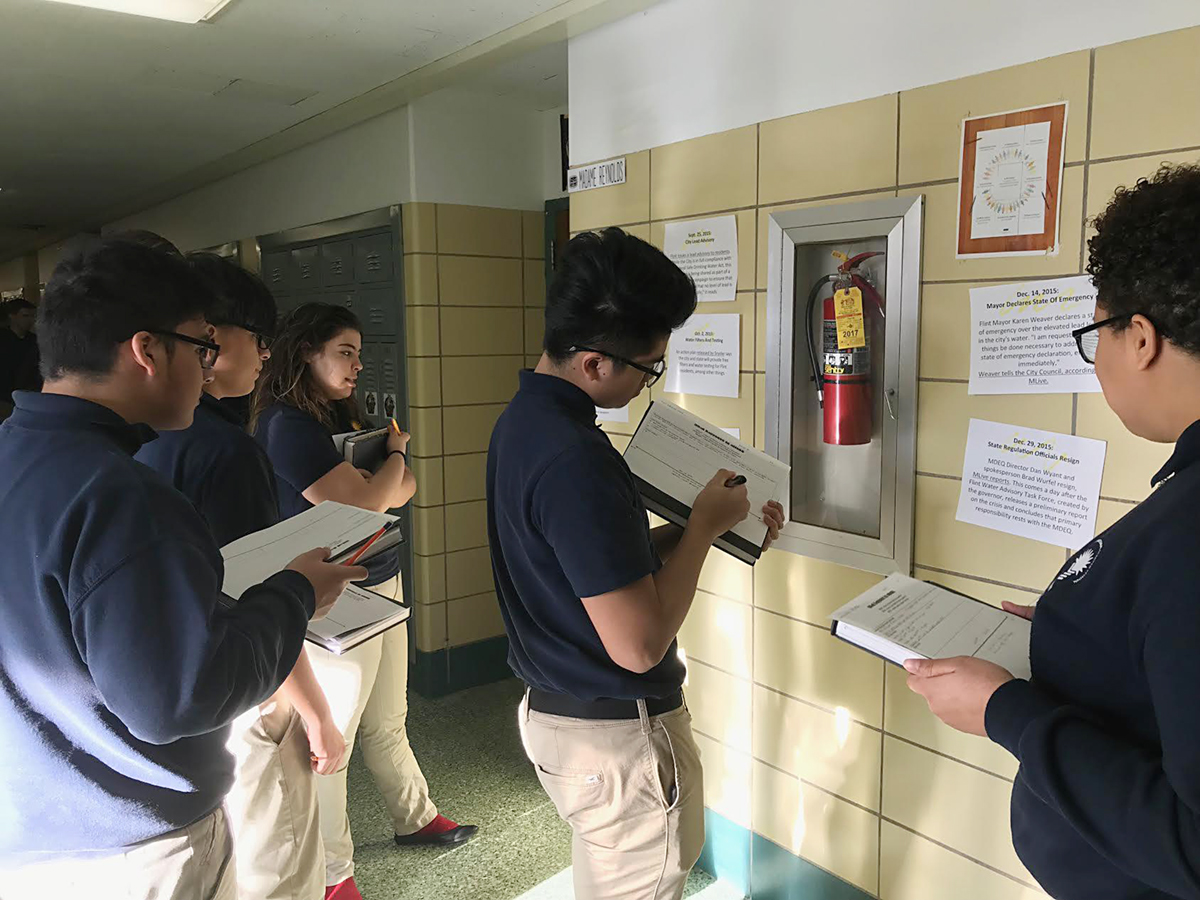

- Gallery Walk: Teacher selects and posts the most important dates of the Flint water crisis on the wall. Students walk through and determine essential trends and themes in the timeline, documenting their findings in their journals.

- Visual Analysis: Students glue images of Jan Tichy’s Beyond Streaming: A Sound Mural for Flint into their journals and use See, Think, Wonder to analyze the images. Students then analyze the participating students’ responses to Tichy’s project in order to understand how the artist and students collaborated to address the Flint water crisis.

- Class Discussion, Analysis & Journal Reflection: Students analyze and discuss how Beyond Streaming impacted change in Flint.

- Extension Questions: How can high school students be change agents? How does Tichy’s art respond to Flint’s water crisis? How does Tichy’s project relate to your research question?

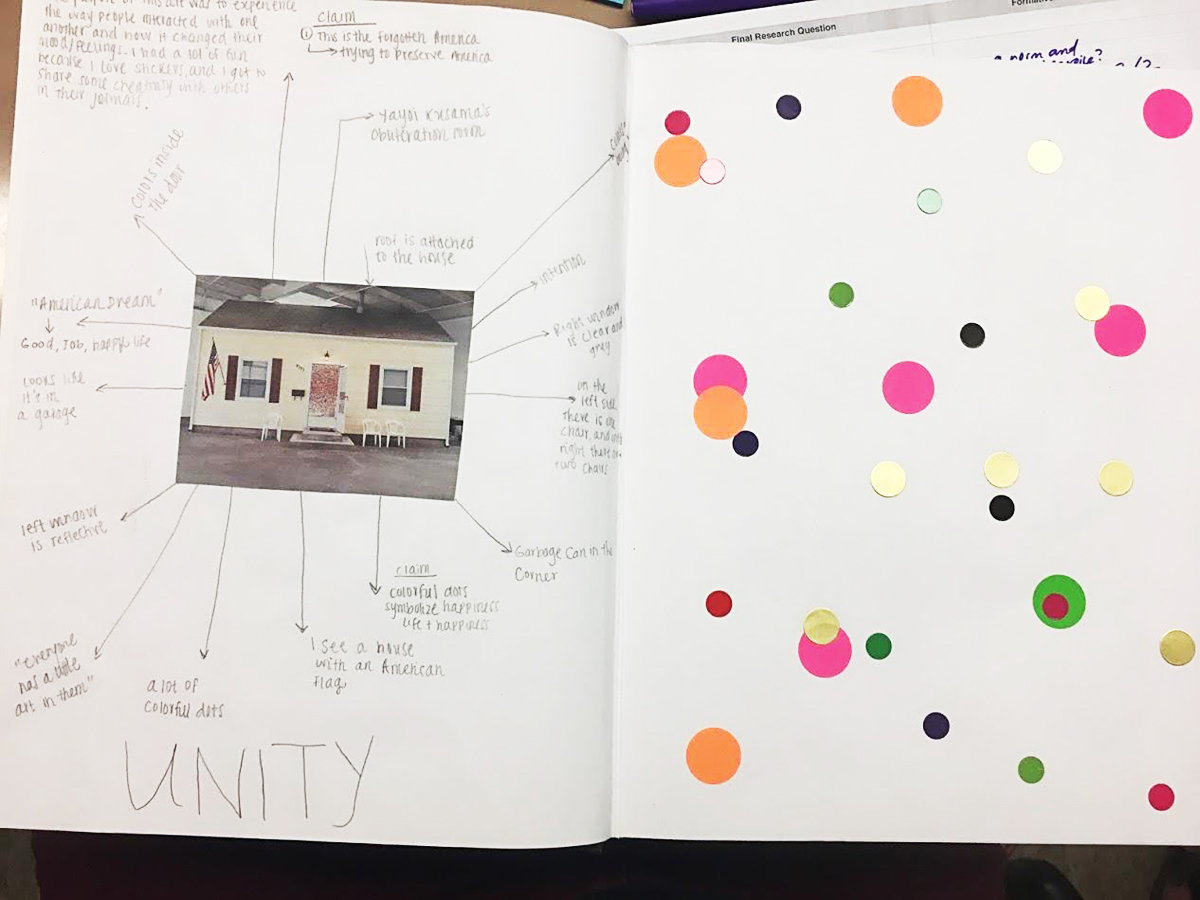

Project 4: Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room and Community Connection

- Visual Analysis: Students view and analyze Kusama’s Obliteration Room, writing one word that summarizes the purpose of the project.

- Obliteration Activity: Give students a sheet of stickers with instructions on how to perform a similar act of transforming the white surface of a journal page using colored dots. Review expectations for interacting with student journals. Students place stickers in one another’s journals around their previously chosen words.

- Class Discussion, Analysis & Journal Reflection: What is the purpose of Kusama’s Obliteration Room based on our experience and re-enactment?

PART 4: EXPLORATION WITH FIELD TRIPS — ART AS EXPERIENCE

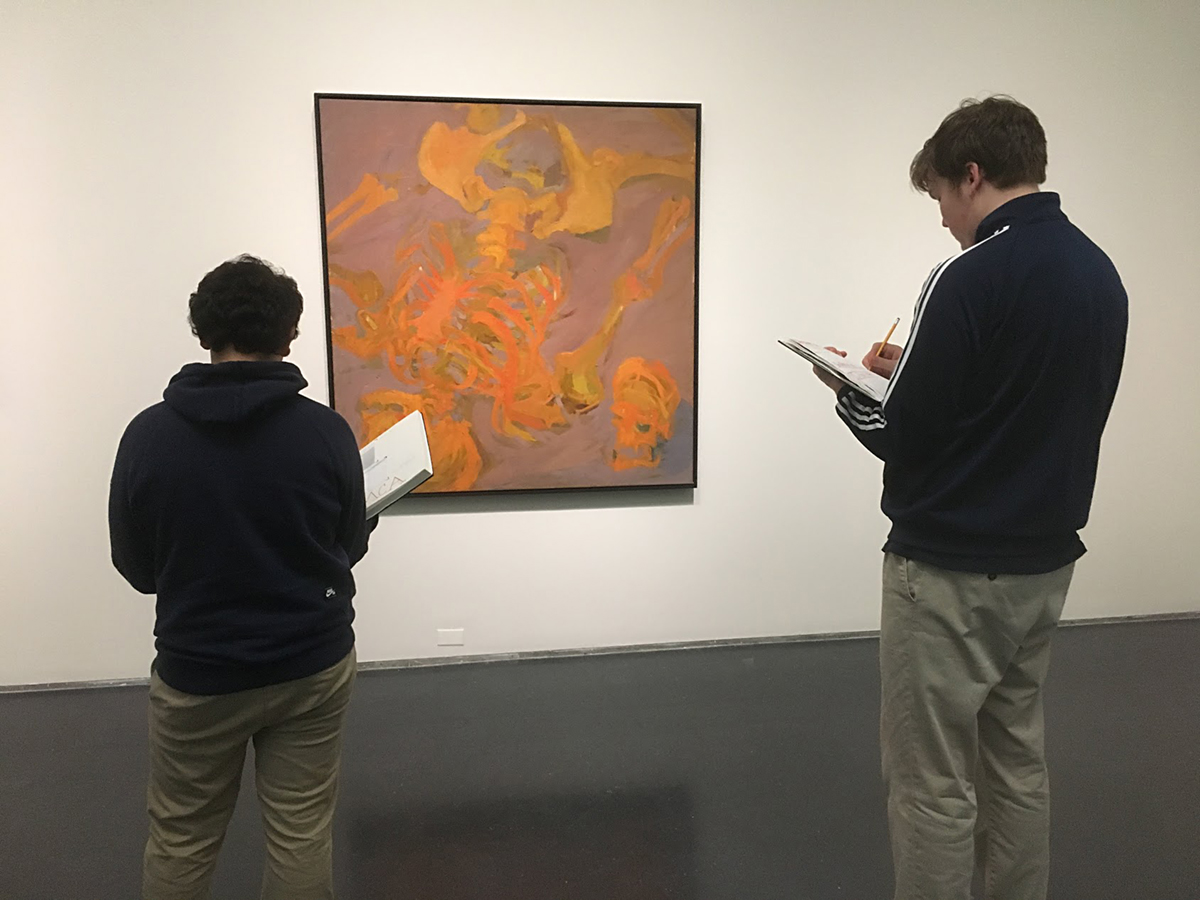

MCA Visit

Students create their own graphic organizers focusing on their research questions in their journals. Students collect evidence from art objects, placards, and artist guides to answer and reflect on their research questions. The visit reinforces students’ understanding of how contemporary artists use research to inform and create artworks.

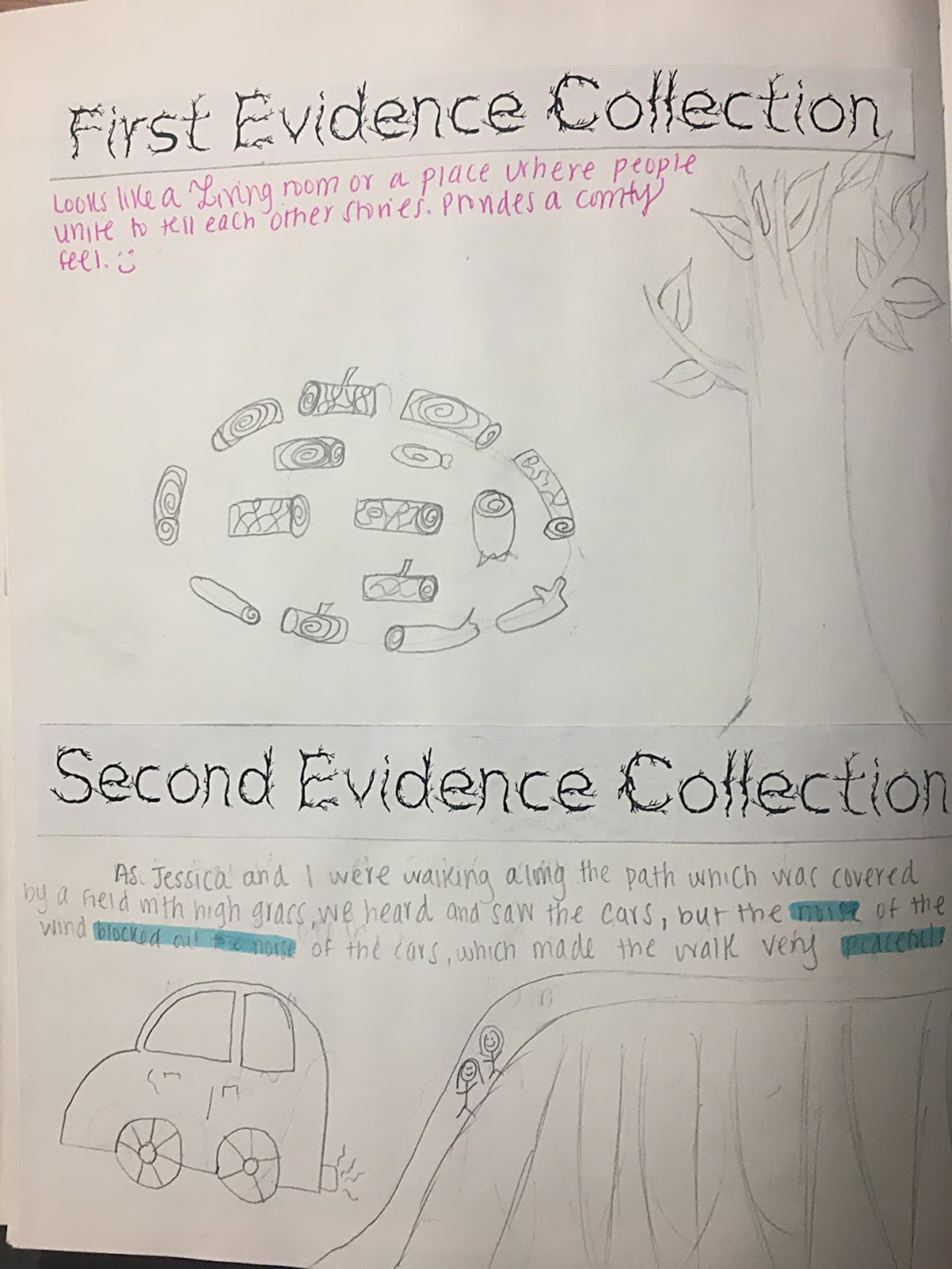

North Park Nature Conservancy Walk

- Guide students on a nature walk at a nearby park. Students create their own graphic organizers focusing on their research questions in their journals.

- Students collect evidence from their physical surroundings and consider the intersections of nature and art. Students connect their walk to the artwork of Ana Mendieta and the literary works of Henry David Thoreau and the concept of living deliberately.

- Back in the classroom, students further connect their experiences in nature to the concept of death, and collaboratively explore questions about life and death using their journals.

PART 5: APPLICATION THROUGH PERSUASIVE WRITING + APPLICATION

- Using the visual and written evidence they have collected in their journal throughout the semester, students write a persuasive research paper answering their research question.

- After writing this research paper, students create pitches for socially-engaged art projects based on their answer to the research question. The project must involve the active participation of the school community in some way.

- Students discuss and respond to pitches created by other students.

- After this step, if time allows, students choose one project as a class and work collaboratively to create it.

- Sample Project: A student created a series of masks for students to wear to shelter emotions, in response to his research question, “How can art help men experience emotions?”.

Materials

- Journals

- Glue sticks

- Color copies

- Markers, colored pencils, etc.

MCA Connections

Visiting the MCA was the highlight for the students near the beginning of the project. By analyzing Amanda Williams’s art in person, students were empowered to create their own art in her style of socially engaged works. It was a highlight of mine to see students point to Williams’ work and exclaim, “I know that!” Amanda Williams’s Color(ed) Theory and Paul Chan’s Little Lower Layer were particularly influential in guiding students’ research in this project. Amanda Williams’s art was the focus of a full week of analysis, and students also created their own “Museum of Value” based on her work. Paul Chan’s work was used at the beginning of class as a thought starter for discussion and analysis.

References + Resources

Education System, Awantha Artigala

The Waiting Room, George Tooker

Elizabeth and Hazel, September 4, 1957, Will Counts

Guernica, Pablo Picasso

Man on a Wire, Philipe Petit

Untitled (Perfect Lovers), Felix Gonzalez Torres

Man at the Crossroads, Diego Rivera

The Obliteration Room, Yayoi Kusama

TM13, Nick Cave

Untitled (2017), Farzad Kohan

Iceman Crucified #4, Ralph Fasanella

Undiscovered Distances, Ilana Emilia

Festival, Daniel Celentano

State Names I, Jaune Quick to See Smith

Money, Mel Bochner

Color Palettes, Amanda Williams

Diary, December 12 1941, Roger Shimomura

Little Lower Layer, Paul Chan

Manifest Destiny, Alexis Rockman

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, Damien Hirst

Body Tracks (1974), Ana Mendieta

Hampshire, 1 November 2013, Andy Goldsworthy

La Venedita (Little Deer), Frida Kahlo

Before I Die, Candy Chang

Untitled , Felix Gonzalez Torres

Hiram Maristany

Beyond Streaming: A Sound Mural for Flint, Jan Tichy

Flint, Ti-Rock Moore

RUSH MORE, Kerry James Marshall

Tank Man, Jeff Widener

Death of Alan Kurdi, Nilüfer Demir

Abi Wilberding

CICS Northtown Academy

About Abi Wilberding

For the past four years, Abi Wilberding has been teaching English and Writing at Northtown Academy in Chicago (specifically student choice classes like “Race and the Criminal Justice System” and “Art into Action”). Abi earned a B.A. in American Studies and Educational Theory from Smith College and a M.Ed from Loyola University. Before Abi taught at Northtown, she taught at a non-profit called GirlForward, working to empower refugee girls, she trained teachers in Cuba through USAID, and she ran an after-school program in New Zealand. Abi is passionate about progressive models of education, responsive instruction, her partner, Brandon, and her two cats, Beans and Tiny.

Abi Reflects on the Project

Throughout the course, art inspired students to share their own stories, and the community in the classroom honored these stories, learned from them, and incorporated them into their own writing and research. The art we studied functioned as a bridge between the classroom and the world outside school. During the “Museum of Value” project inspired by Amanda Williams, students shared jokes, experiences of loss and resilience, and their heritage.

Students became researchers, writers, and potential activists in the school and surrounding community. The most important lesson students learned was to be conscious observers and active researchers in their lives. Creating their own research questions validated student interests and lived experiences. Analyzing art as activism motivated my students to also consider activism through research and consider themselves as powerful activist researchers.

I loved collaborating with other adept and creative educators at the MCA, and I’m excited to continue using journals as a means of engagement and empowerment. Last week, a student approached me in the hall and told me journals would make all of their other classes better. Another student recently came to me to talk about how much they loved analyzing issues that were happening in the world around them through art. While learning about Murakami’s arhats and the tsunami in Japan, one student said, while tearing up, “This is so real”.

My favorite part of teaching is when learning becomes “real.”