Inviting Student-Artists to Define Art in Our Society

By Rita Crocker Obelleiro

This project is a complete course curriculum for a new class called Art and Society, made up of four diverse student-artists. All students shared a desire to explore art’s influence on society. In a survey at the beginning of the school year, student-artists wrote that they enrolled in the class because they wanted to create art “with purpose,” to “create change,” or to “impact others.” The projects made in this course both question and define the role of art in contemporary society through student-selected themes and socially-engaged, student-directed projects. Activities took place in the classroom, within the school, in community art spaces, in museums, and outdoors. Depending on the project and proposal of each student-artist, project participants included other students in the school, museum employees, and youth and adults in the community. The culmination of students’ artworks provide a visual definition of art as they create and experience it.

Goals

- Student-artists will reflectively define the functions of art and artists in society as a group and with outside participants using readings, media, museums, alternative spaces, and artist and community member interviews.

- Student-artists will research artists, explore how audiences are impacted by art, and teach themselves new technical skills and art processes so that they become proficient in their practice.

- Students will gain confidence and take ownership of their work by learning how to document, present, write, and speak about their work with members of their communities.

- Student-artists and the artist-teacher will work together to examine the ethics of artistic production to guide choices and foster connections between student-artists and their communities using socially engaged artworks.

Guiding Questions

- How is art defined and how are artists defined in society by the youth we collaborate with/teach?

- Why and how do societal perceptions of art and artists influence the role that art has in society?

- How can we create works of art that help facilitate audience engagement and encourage critical citizenship?

Documentation + Assessment Strategies

Student-artists were responsible for documenting a range of their work from different perspectives and with other students, faculty, staff, family and community members. Student-artists were also asked to document their work in progress using audio, video, photo, and/or social media. If the project was ephemeral, documentation also provided evidence of the project’s existence.

We assessed the projects as a group during verbal critiques and based on rubrics that student-artists wrote and used to self-evaluate. We also discussed the testimonies of participants and talked about how viewers, the audience, or active participants determine the success of a project.

Learning Activities

Timeframe

17 weeks, 2-3 class meetings per week for 75-minute periods

SETTING THE STAGE

Begin the first class by surveying student-artists about why they chose the course. Provide an icebreaker that allows students to articulate their ideas about creative agency. The survey may take anywhere from 20-30 minutes to complete, especially if students are asked to produce a visual response. Discuss some of the responses. Afterwards, work together to collectively list the purposes of art in society and the roles of artists in society (such answers can be generated through the icebreaker exercise). Keep the compiled list, which will be reintroduced after Project 1. After completing Project 1, revisit the questions about the purpose of art and artists in society. Compile a second list before comparing it to the first. Student-artists and the artist-teacher reflect on the overlaps and conflicts between these two lists, using this information to identify issues with arts funding, support for art education, support for artists, and the role of arts in different socio-economic communities. Student-artists may also note what has shifted about their perceptions of art or artists after completing Project 1. This second list will be the backbone of the course and can be used to identify the principal themes students will explore.

TRANSITIONING FROM THEME TO THEME

How does one project theme connect/spiral to another?

As we transition from one project to the next, we review how the approaches student-artists have used may become an integral part of current project themes. They may also discover, as we have, that the final collection project involves an amalgam of themes and approaches. As projects progress, students document all phases of the work to be used in a culminating online exhibition that serves to help visually define the function of art in society according to this group of students.

PROJECT 1

What is Art, Who are Artists?

Student-artists identify issues in our community and select a concern to address through artmaking. The artist-teacher guides students in drafting their first project proposal, and provides a generous imaginary budget that student-artists have to ‘spend’ to better serve their/a community. Student-artists review their proposals, while the artist-teacher guides discussion of the ethical considerations in their projects using multiple prompts.

For example: Does the community want this project? If so, how do you determine community members’ participation or collaboration? How do you create dialogue around the community’s values? In what ways have you assessed the needs and desires of this community? Following the discussion, student-artists rewrite project proposals to align with the communities they intended to serve. Student-artists maintain sketchbooks about their reflections and the daily prompts throughout the semester.

PROJECT 2

Intro to Social Practice

Student-artists read a series of articles from Education for Socially Engaged Art and Beginner’s Guide to Community Based Art. They then create written case studies about 13 socially engaged artists using Art21’s Creative Chemistries Playlist. After this, student-artists revisit the lists about art and artists in society that they created during the Icebreaker activity (Setting the Stage) and edit them according to their new insights. The artist-teacher and student-artists collectively distill their ideas about the purposes of art and artists into four themes: 1) Expose/Create Awareness, 2) Create Action, 3) Memorialize, and 4) Collect/Archive/ Sort. These themes will serve as the basis for their projects throughout the semester. Student-artists decide the sequence of investigating each project theme and the due dates for each artwork. They recognize that despite theme structures, artworks often touch on other themes—such as an action being used to expose, or an archive being used to memorialize. Therefore, the theme will not determine the medium, but rather directs the learning and making processes and the inclusion of project participants.

PROJECT 3

Interview with a Museum

Student-artists incorporate the MCA and other museums into their research on social practice and the function of art institutions in society by “interviewing” a museum. Give student-artists a list of activities to complete during their visit, which include collecting an object from the museum (i.e. publication, take-away, gift), interviewing a museum worker (i.e. museum guard, coat check assistant, curator), and documenting how the museum serves the community audience. Back in the classroom, student-artists share their interviews in the form of video, audio, digital slides, and/or photography. The goal is for students to see the museum space as dialogic by sharing their analysis of how their visits and the presence of those who work at the museum activate other elements of an institutional space.

PROJECT 4

Expose/Create Awareness

Student-artists respond to a chosen issue, concern, or idea they want to ‘expose’ to the public. Publics can vary, from the family to a wider audience. Each student-artist writes a proposal for their topic, creates a budget, and discusses their project in small groups. The artist-teacher provides examples of artworks that ‘expose’ by artists such as Amanda Williams, Carrie Mae Weems, and LaToya Ruby Frazier. Student-artists identify and survey project participants. Participation can vary: People can provide written and verbal data, scenarios, photography, or even their body as part of the work. During our class, student-artists created installation projects that included exposing sources of anxiety and stress in our school, the lack of monuments to women, and the difficulty of confronting negative self-imagery.

PROJECT 5

Create Action

Begin by watching the MCA Michael Rakowitz video and looking at artists such as Oliver Herring, John Baldessari, Yoko Ono, and Coco Fusco. Using these artist to model action, student-artists collectively brainstorm ways an action can be the reflexive practice of art-making. Invite student-artists to select action-based performance art videos from ubu.com, and discuss sign, symbol, ritual, and story as starting points for their Create Action projects. Student-artists are assigned other chapters from the Beginner’s Guide to Community Based Art, which provide examples of signs, symbols, stories, and rituals. From the videos and chapters, student-artists formulate guiding questions for their projects.

Examples of these questions are: What kind of rituals do we engage in? What symbols exist that we are so used to we no longer see? What actions repeat in our history? In our families? How do we connect with others? How can a gesture, greeting, or dismissal be reimagined?

Students respond to their questions through actions designed to engage their peers in contemplation of sign, symbol, ritual and/or story. To prompt ideation, the artist-teacher can invite student-artists to physically alter their standard classroom arrangement. In our classroom, it was an opportunity to interrupt the space and any associated rituals. The installation was left up for several days and other students were invited to add or take away from the arrangement. Student-artists documented the space and responses to the space as it evolved, and before deinstallation.

PROJECT 6

Memorialize

Begin this project by looking at the Mural Arts Program Monument Lab to contemplate how our society memorializes objects, people, experiences, places, connections, and the passage of time. Discuss with students how both the creation of and destruction of memorial objects can serve to memorialize. Student-artists can engage in further dialogue about the ‘negative space’ around a memorial, the lack of certain memorials and proliferation of others, such as the addition and erasure of culturally specific memorials. In our class, this project took place during the destruction and removal of confederate monuments. We looked at free curriculum such as the All Monuments Must Fall syllabus to analyze how the public is responding to the erection and destruction of historical monuments.

Student-artists reflect on what they wanted to memorialize through additive or subtractive actions. Collective participation is an important element of public monuments and memorials, so we address the role of the public in creating, destroying, or responding to student-artists’ ideas. In our class, student-artists invited others to dissolve childhood books, seal them in plaster, and then install them publicly. Other projects included capturing images from forgotten archives, and writing dates on found keys to document loss.

PROJECT 7

Collect/Archive/Sort

This project is introduced after Project 1 to provide student-artists adequate time to build their collections and to present them meaningfully. For this project, have student-artists look at Faheem Majeed’s Floating Museum, Tania Bruguera’s Arte Util, Mark Dion’s river collections, and Fred Wilson’s museum rearrangements at the Baltimore Historical Society, as well as the collections from students’ Interview with a Museum project. Student-artists are given time to sort and categorize their collection and then present the collection as an archive, personal collection, or interactive piece. In our class, collections ranged from responding to requests for beautiful photographs, gathering fabric swatches from childhood outfits paired with a test tube full of french toast scent, and developing a fashion brand that counters sexual discrimination.

PROJECT CONTINUATION

Digital Exhibition to Physical Exhibition

All student artworks were added to a public Tumblr page that serves to visually define the function of art in society according to this group of students. Student-artist work made outside of this course has also been added there to document the student-artist-researcher practice. As the course shifts each year, we hope to curate a physical exhibition in a community space that could accompany the course’s digital presence.

STUDENT RESPONSES

Discussions about privilege and power have shifted during the course. I have continued to hand over the decisions about the class structure to the students. In recent feedback surveys student-artists wrote, “[we] are not seen as knowing less than the teacher,” but rather as a source of knowledge and experience. As I allowed them to take more ownership, I found ways to offer individualized support. When they needed an adult to make a project happen, I was able to speak with administration, other adults, parents, or teachers on their behalf.

Materials

Material needs changed according to each student-artist’s project. The budget provided by the MCA was divided by project and issued based on proposals. Materials have included stamps, etching cream, a digital text display, calligraphy pens, a hamster ball, balloons, catalogues, a candy container, 100 old keys, and oranges.

MCA Connections

Student-artists were able to collect ideas, information, and conversations from our guided tour at the MCA. We reviewed images and materials from the visit to reflect on our own making. Student-artists also used the MCA and its resources for the “Interview a Museum” project. The work of Michael Rakowitz, Edra Soto, and Amanda Williams sparked conversation and inspired student-artists’ work.

Throughout the course, I introduced new artists, artworks, visual culture, media, or articles that reflect the intersections of art and society. Using resources provided by the MCA or collected by student-artists from the MCA, I focused on guiding concepts such as art and activism, art and social consciousness, and art and archive.

References + Resources

Books

- Education for Socially Engaged Art, from the Pablo Helguera archives

- Beginner’s Guide to Community Based Art, Mat Schwarzman and Keith Knight

- Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution

- Living As Form, Nato Thompson

- Art and Social Justice Education: Culture as Commons, edited by Therese M. Quinn, John Ploof, and Lisa J. Hochtritt

- Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures, 1960s to Now

Websites

Videos

Prompt Examples

Viral videos, news headlines, or other topics that impact student-artists, introduced at the beginning of each class

Rita Crocker Obelleiro

North Shore Country Day School

About Rita Crocker Obelleiro

Rita Crocker Obelleiro graduated from Maryland Institute College of Art with a BFA in Painting, the University of Pennsylvania with an MFA in Painting and Certificate in Graphic Design, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with an MAT in Art Education. She received a Fulbright grant for Painting and Printmaking in 2012. Rita is the Visual Arts Department Head at North Shore Country Day School and co-teaches the Drawing and Painting Summer Institute at Interlochen Center for the Arts.

Rita Reflects on the Project

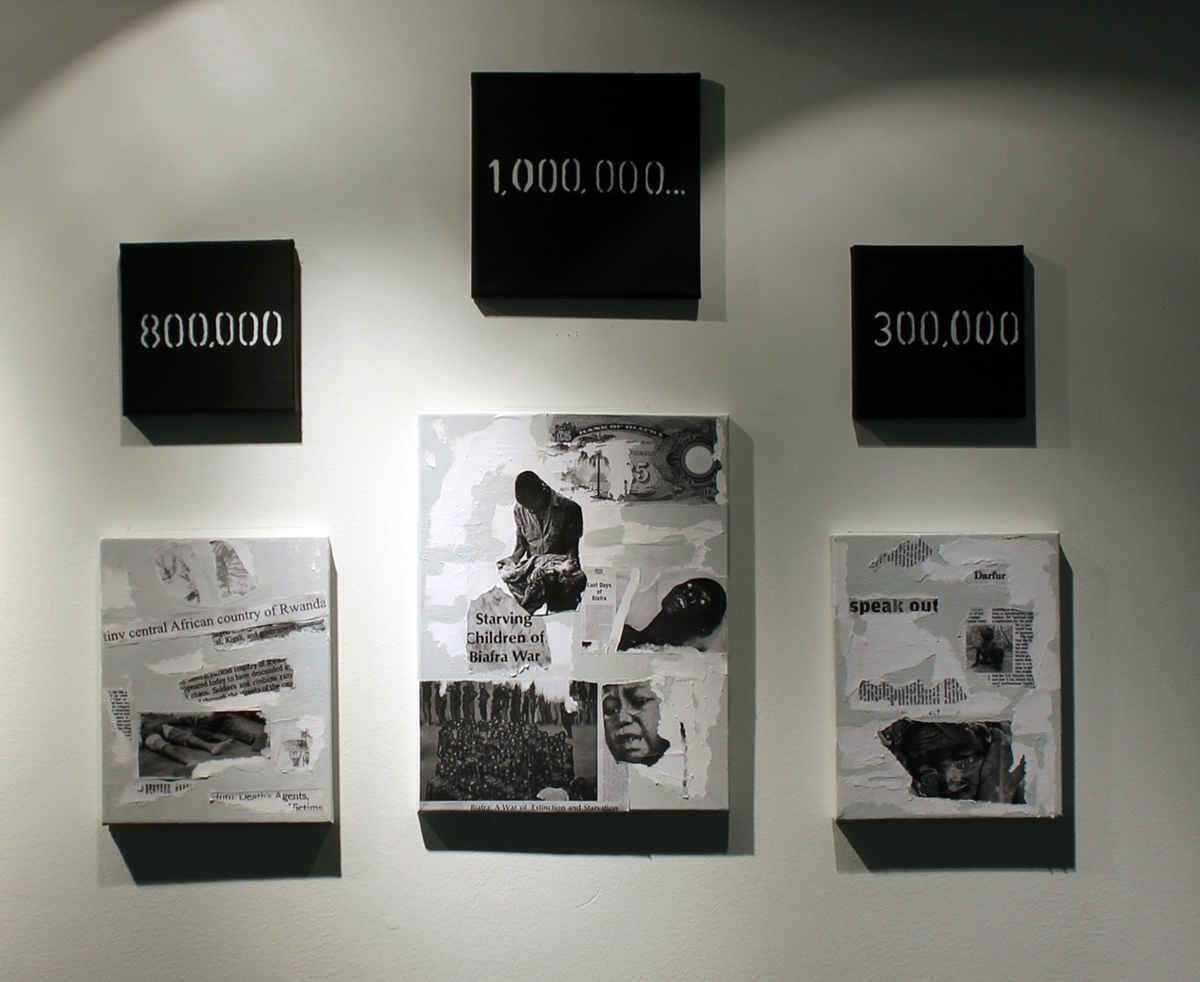

In light of recent events, the class has become a space to discuss controversial cultural issues including the politics of the body, the Biafra war, the treatment of racehorses, celebrity social campaigns, misappropriations by the fashion industry, confederate statues, and vigils for rock stars. The introduction of prompts designed to spark conversation about contemporary issues at the beginning of each class has helped to both initiate conversations and provide artistic references for student-artists.

One challenge I encountered was that despite handing over the power to decide the content, due dates, and structure of the class, the flow of the class that student-artists established started out as overly structured. I noticed that they were modeling our class based on the experiences of their other classes and did not challenge that model, nor did they feel they could challenge it. At that point, I asked them to rearrange the room to connect the walls, floor, and ceiling for incoming classes during our Create Action project. Some were visibly uncomfortable with this, while others were excited to turn chairs upside down, line up self-portrait mirrors, and build structures with yardsticks. Breaking the steady flow and structure of the course by disrupting the space was an important way for us to regain a sense of movement, invite chance, and speak about a fluxus practice.

The remainder of the course became more fluid once we disassembled our construction and revisited the purpose of the space. Upon reflection, one member of the class said she did not recognize her own rigidity until we disrupted the routine of the class. I saw student-artists engage in broader thinking when considering how their work could contribute to and belong in larger social contexts.