de(Construction)

By Jagoda Borkiewicz

How do we decide what is valuable? How can value and ownership be fair or unfair? Third graders in a self-contained cohort for English Language Learners at Horace Greeley Elementary, a Chicago Public School, created a socially-engaged project protesting injustice. Building on extensive study of native peoples of the Chicago area and the Trail of Tears, students visited the Museum of Contemporary Art to engage in critical dialogue about questions of value and ownership, and explored their own gentrifying neighborhood using photography. They engaged their school community by staging a silent protest, writing letters to school leadership, and interactively presenting their documentation in a public gallery.

Goals

- Students will be able to describe aspects of the peoples native to Chicago, and explore injustices that Native Americans and people of lower socioeconomic status have experienced since 1492.

- Students will experience field trips to the MCA to learn about contemporary art and critical dialogue.

- Students will work together to create a socially-engaged artwork responding to their academic study of native peoples.

- Students will be able to demonstrate how concepts of value and community relate to their lives.

Standards

- SS.IS.2.3-5: Create supporting questions to help answer essential questions in an inquiry.

- SS.IS.3.3-5: Determine sources representing multiple points of view that will assist in answering essential questions.

- SS.IS.7.3-5: Identify a range of local problems and some ways in which people are trying to address these problems.

- SS.CV.1.3: Describe ways in which interactions among families, workplaces, voluntary organizations, and government benefit communities.

- SS.H.2.3: Describe how significant people, events, and developments have shaped their own community and region.

- VA:Cn10.1.3 Develop a work of art based on observations of surroundings.

- VA:Re7.2.3 Determine messages communicated by an image.

Guiding Questions

- How do you treat something that is valuable to you?

- Why is it important to think critically?

- How can you use your creativity to speak up about ideas that matter?

Documentation and Assessment Strategies

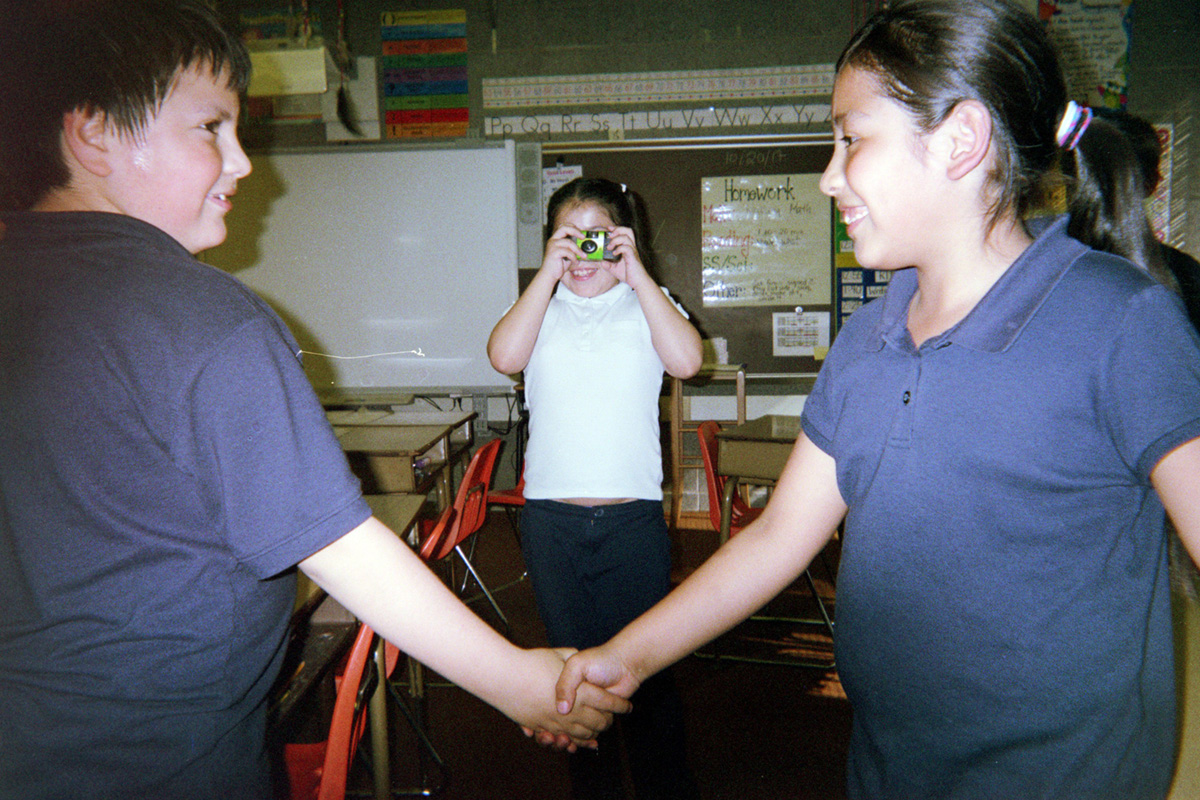

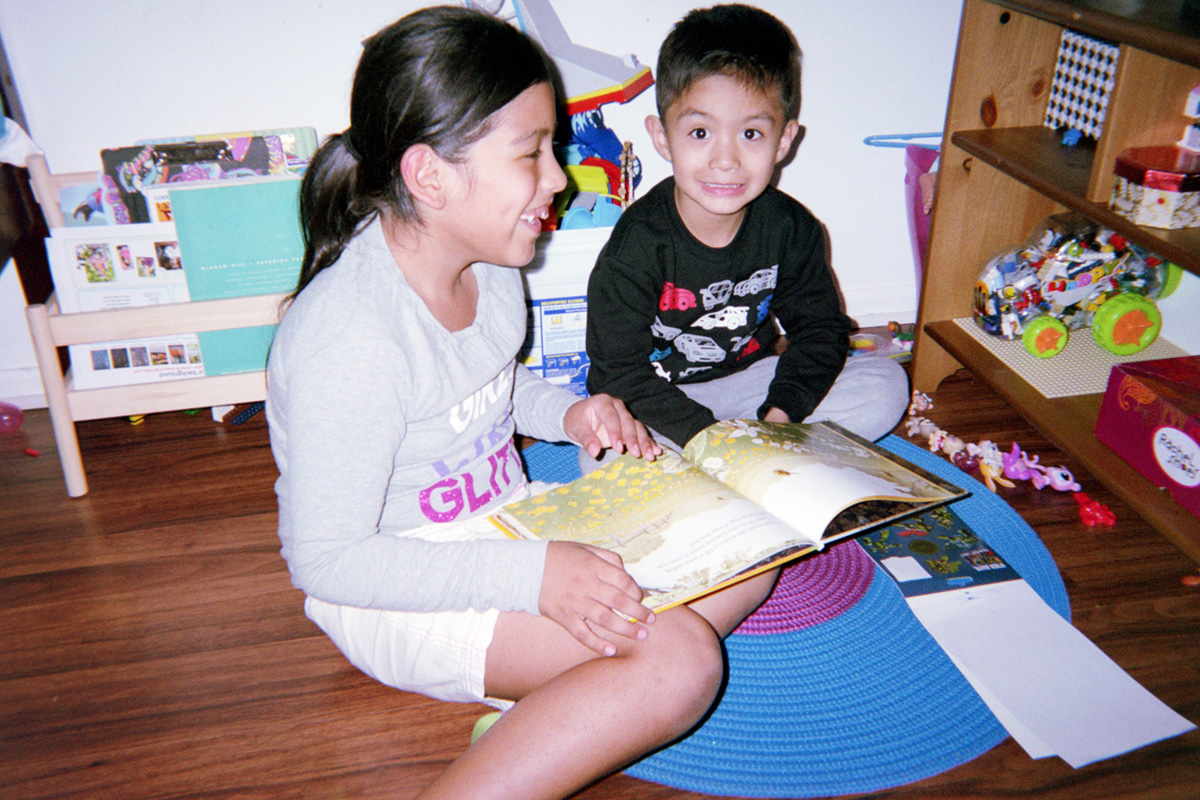

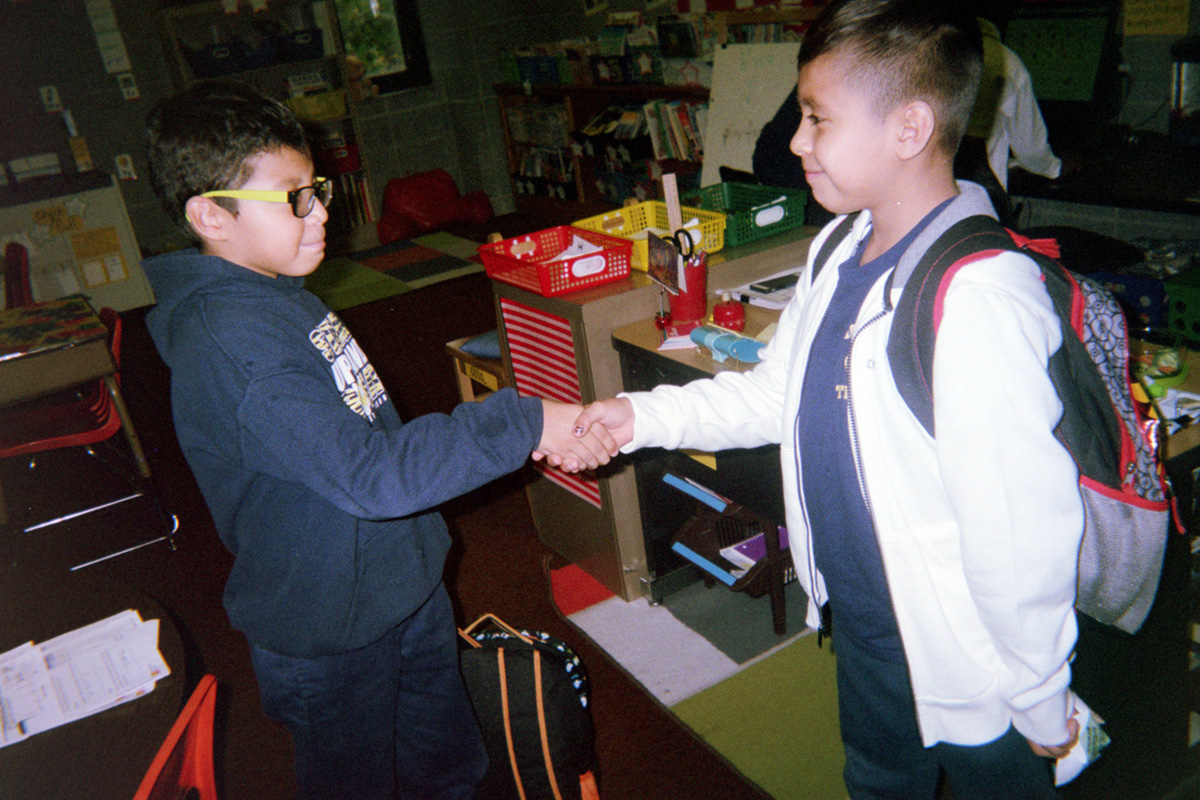

Students were inspired by historical photographs of students protesting and became interested in photography. They were provided with disposable cameras to independently lead their own documentation.

Because the curriculum was driven by the students, assessment was continually used as we were creating, in order to plan for each next phase in our project’s development. Students assessed their work by having frequent verbal reflections about how the project was progressing and whether it was bringing us closer to our goals. Students’ artistic products demonstrated their understanding of large concepts. As students got more support and attention for their work, they were satisfied that their work had felt meaningful and been effective.

Students met their goals set for this investigation. They explored injustices that Native people faced since 1492, experienced field trips to the MCA, created socially-engaged artwork, and displayed their installation in a public space, getting feedback from visitors and viewers eager to join us in sending our message. Students have also deeply internalized the concepts of value and community—when one of my students was being bossy, a classmate asked her to stop acting like Columbus!

Learning Activities

Setting the Stage

In this ongoing unit, 15 of my students in English Language Learning (two in Special Education) began their investigation alongside the 3rd grade Social Studies curriculum, scheduled three times a week for 45 minutes. We needed to dedicate more time to this investigation, and it became the topic of our persuasive writing unit, taking place three times a week for an additional 45 minutes. Instead of writing persuasive essays about which classroom pet they thought was best, students wrote to the mayor asking him to change Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Even though I altered the established prompt, I kept my team’s pace and met the same standards. As students became more invested in the project, they asked for a working lunch and/or recess. They knew that this project required additional time, and they have never lost their drive in the 7 months we have been developing it. To strengthen social-emotional skills and understanding of Indigenous traditions, my students have daily morning meetings and afternoon pow-wows where they hold a communal problem-solving gathering, when the class or a classmate is in ‘disequilibrium.’ We have done this every single day without exception since October, transforming every child into a care-giver and care-seeker when there is a problem.

STEP 1

Knowledge Base: Understanding the Potawatomi People

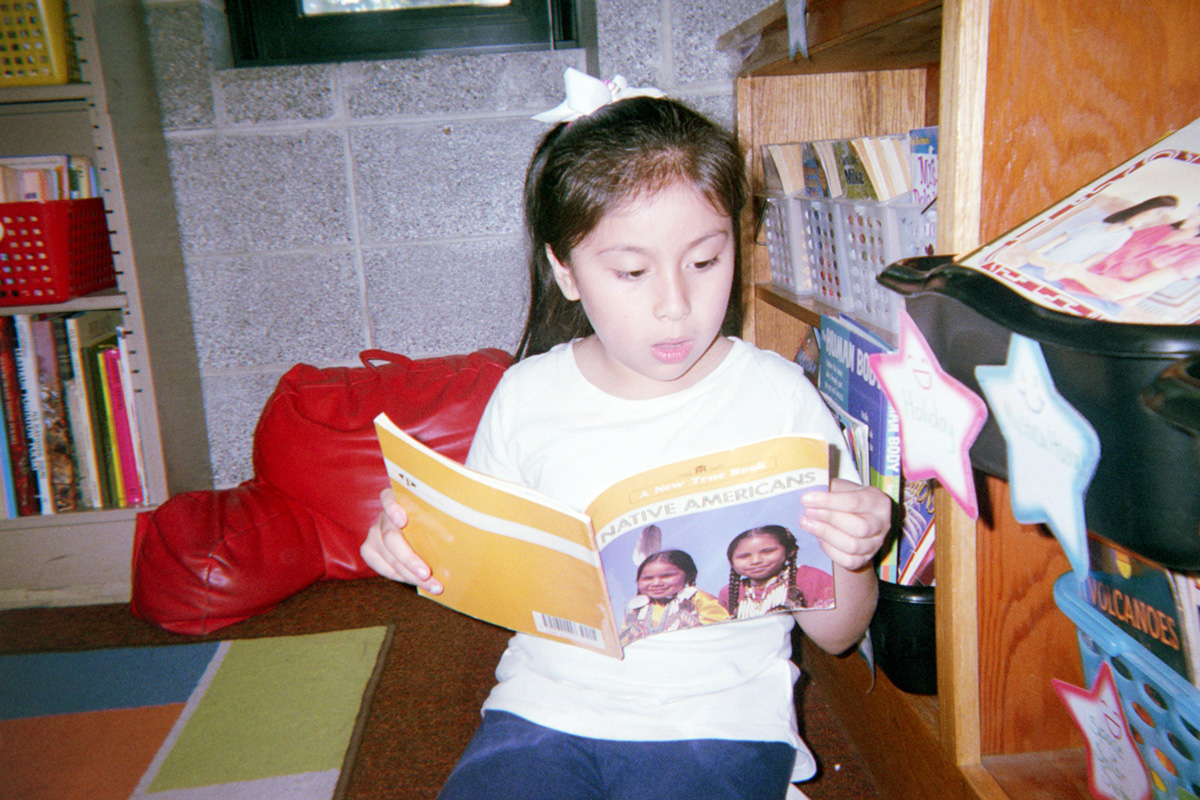

Before beginning to explore socially-engaged art approaches to social issues, students complete a full unit about the first people of Chicago and their ways of living in the past. This unit, created by the 3rd Grade team at Greeley Elementary School, includes a study of art, homes, foods, roles in society, and transportation.

STEP 2

Layering Critical History

Once students demonstrate mastery of the history of local native people, the teacher introduces the concept of injustice, and presents a lesson on 3rd-grade-level examples of ways the native peoples of North and Central America have been treated unfairly since the arrival of Christopher Columbus. Students engage in critical dialogue to explore their thoughts and feelings about native peoples, Columbus, and social injustice.

STEP 3

Introducing Contemporary Art

Students visit the Museum of Contemporary Art to engage in conversations about art objects, with special emphasis on power, value, and ownership.

STEP 4

Anti-Columbus Day Protest

After discussing the ways that art can express ideas that matter to artists, students work as a collective to design a two-part protest to Columbus Day in order to help other students and their teachers understand their collective position that Columbus Day represents unfairness. Specifically, students design t-shirts with slogans and wear them to a pep rally on Columbus Day, and students write letters to their principals and to the mayor requesting to change the name of the holiday.

STEP 5

Reflecting on Socially-engaged Work

The third graders broke out into student-led groups which they picked based on their interests and talents. They wrote and performed a silent skit recreating their interpretation of Columbus’ arrival, created abstract art depicting the struggles of the Potawatomi, and learned phrases and greetings in Algonquin, which they showcased at a performance held for a group of students, teachers, and our principals.

STEP 6

Inquiry into Values

How do we decide what is valuable? Building on content from Amanda Williams’s artwork and The Lorax by Dr. Seuss, students generate a list of things they value more than money. Students compare and contrast themes from The Lorax with their existing knowledge of Columbus and the legacy he left behind. The teacher asks students what they think the Potawatomi value, and collectively decide they probably value nature.

STEP 7

Photography Walks

Sparked by a student idea that the legacy of Columbus is connected to the way gentrification displaces people from the school neighborhood, the teacher leads the class on community walks around the school to look carefully at surroundings, including apparent gentrification. Students use disposable cameras to capture points of interest, they discuss what they see, and they interview a construction worker on the site.

STEP 8

Reviewing our photographs and making an installation

We looked at our photographs—What things of value did we capture and why? What things do we value as a class, compared to the Potawatomi, or even Columbus? We returned to the MCA for a field trip to look at how the artwork was displayed. How do artists display their work to share their messages? What material choices did they make, and what do those choices communicate? We discussed ideas of symbolism too. How could a material be a symbol for something bigger? What might our project look like physically in order to communicate our message? Students wanted to use materials that symbolized value to go along with our images. We decided to use rope and play money because of a connection students found between rope and Mexican ranch culture.

STEP 9

Dollop Display

Students install their works in a local coffee shop that displays community art. In addition to displaying artifacts from their protests, photographs, written reflections, and other documentation, students invite the community to participate in the project by contributing images of things they value to a project Instagram.

Materials

- T-Shirts

- Fabric paint

- Play Money

- Rope

- The Lorax by Doctor Seuss

- Venn Diagram

- Fuji single-use cameras

- Developed photos

MCA Connections

The MCA has inspired both my students and me in various ways. Defining contemporary art and socially engaged art was an important first step in realizing that art is and can be anywhere, and that we are all artists—this was not something we were entirely aware of prior to our visit. I really connected with the artists who presented during our Teacher Institute workshops, and I tried to recreate the passion I felt from them and bring it into my classroom. Once I learned discussion prompting techniques, I was able to utilize them with my students to deepen our learning. Being at the museum also helped us plan and visualize our installation by looking at how artists’ works were displayed.

While at the museum, we focused our attention on Amanda Williams’ work, especially her piece titled It’s a Goldmine/ Is the Gold Mine?. This was a piece we referred back to often, using it as a way to look at value, power, and ownership. Are bricks more valuable when they are painted gold? If a house is determined worthless and is torn down, why are the bricks collected and resold? Who makes these decisions? Is there another motive behind such decisions?

Most of my students had never been in an art museum prior to our visit to the MCA. They were overwhelmed with emotion! We focused on things that grabbed our attention—often the colors and the size of the art. Students engaged in critical dialogue in artist-led tours and discussed the works of Amanda Williams, a large source of inspiration for our installation. Students also participated in a Creation Lab during their second visit, expressing their artistic choices afterwards.

References + Resources

Jagoda Borkiewicz

Horace Greeley Elementary School

About Jagoda Borkiewicz

I was born in Krakow, Poland, and because my parents won a visa lottery to the United States, we moved to Chicago when I was eight years old. It always fascinated and humbled me to know that my parents left their families, credentials, and language behind to potentially provide more for our family. I always connected my experiences as an immigrant with my students and their families. I currently teach the third grade Spanish-Bilingual and Polish Language program at Horace Greeley Elementary School in Lakeview. Prior to that, I taught the third grade Gifted Program and Polish Language at the same school. I moved back to Chicago last year after working in Sydney, Australia for the past two years. Other experiences teaching abroad include work at schools in Spain and China.

Jagoda Reflects on the Project

Initially, this project focused solely on Native Americans. I was not expecting my students to begin making connections to Tent City, and I was surprised that they knew about the removal of the people who lived there. As we continued making connections to various topics and having discussions, issues surrounding homelessness, poverty, race, immigration, and gender became critical in developing our project ideas. After learning about forced assimilation at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and the loss of language and identity that many native people experienced, students began to express their disapproval for certain societal norms. Why did the native boys and men have to cut off their long hair? What was wrong with wearing their traditional clothing? They came to the conclusion that all people should be able to dress and act in a manner that makes them happy. This has inspired us to start making a class music video titled, “Weird is the New Cool” where students shatter expectations, inspiring others to do the same. The biggest obstacle throughout this investigation continues to be finding sufficient time to let students plan and design these projects while keeping pace with the scope and sequence of the established curriculum.