Dear Future Educators,

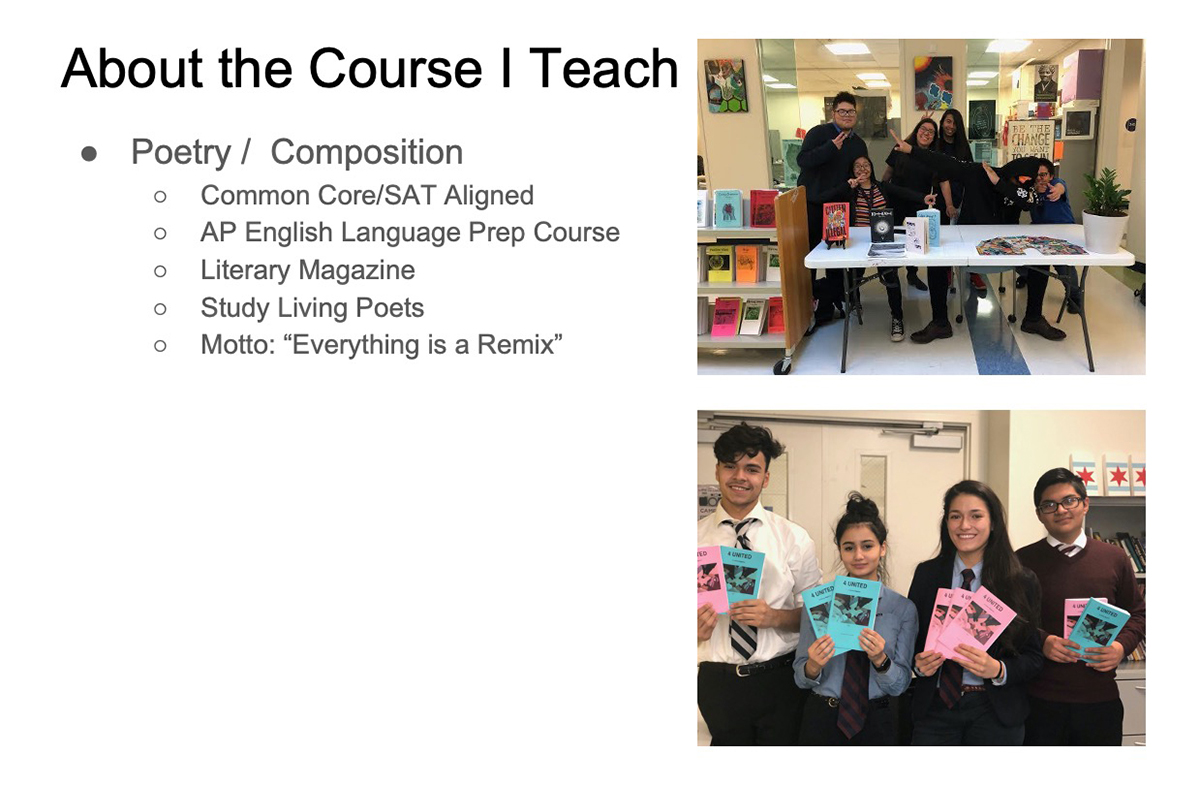

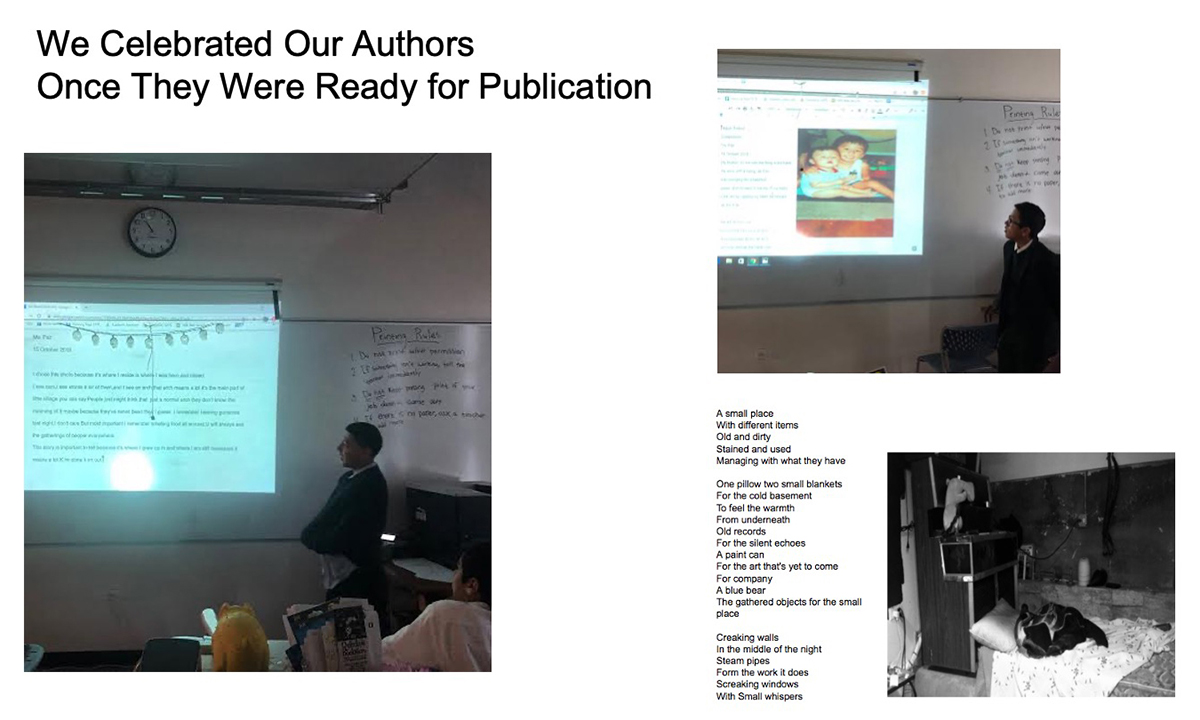

One of my goals has always been to get my students to see themselves as authors. The writing scene in Chicago will one day be taught in textbooks, and I truly believe this movement is spurred by the artistic talent of the city’s youth. I am astounded by the talent I witness day to day in this city, especially in my school. My students are an essential part of the greater conversation about their city. What they have to say is worth hearing; I want them to figure out how these thoughts and messages could be heard—but more importantly—I want them to be proud of what they have to say as authors, artists, and creators.

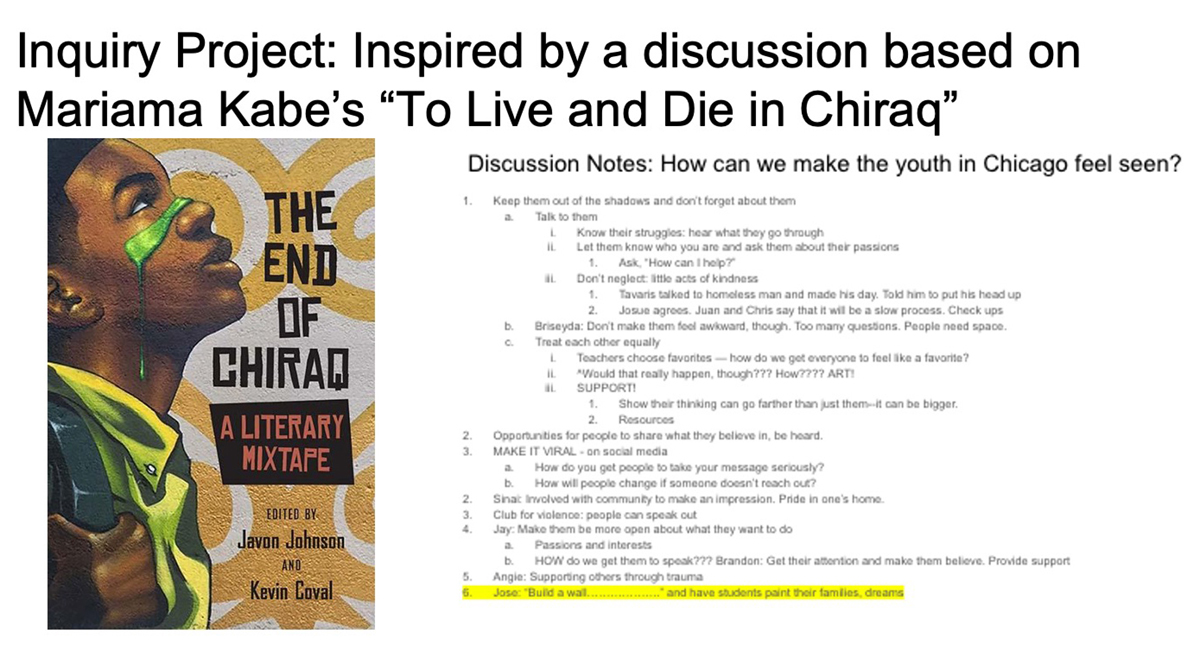

We were inspired by editor Javon Johnson’s anthology The End of Chiraq: A Literary Mixtape. Johnson states, “Whether it was the courtyard kids of Big Red finding joyful ways to transform the otherwise unfriendly space, 'doubling up' families in single units to cut the cost of rent, or other modes of kinship and caring, Conquergood informs us that people, especially those who have been and are disenfranchised by those in power, will always find ways to create for themselves a more livable world” (Johnson, xvii). This idea of creating and bringing together different voices resonated with me and reminded me of my classroom: each student has their own unique perspective belonging to a larger community of voices.

Process

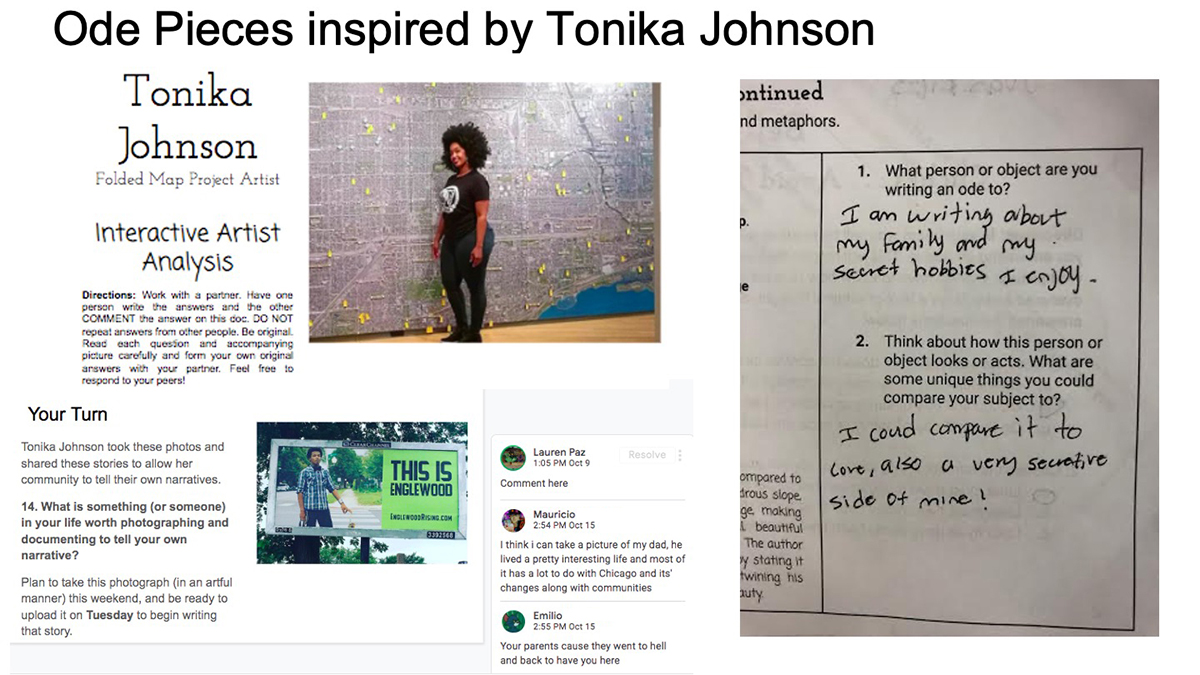

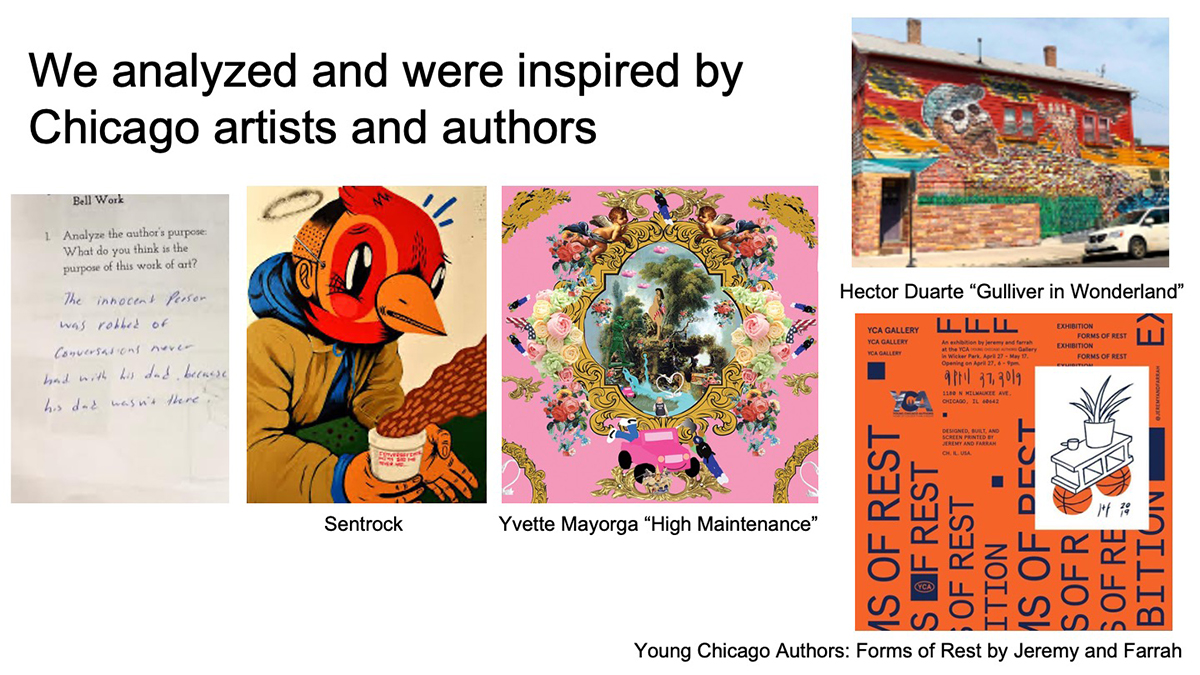

We set out to respond to the question, “If Chicago was a mixtape and you were invited to add a track, what would your verse be?” We studied, analyzed and assessed different authors, artists and thinkers in our Chicago community (those well-known and those we know well) and gave ourselves permission to enter the conversation, as authors and artists. Kirby Ferguson theorizes that everything is a remix: Music, writing, art and even we as people are remixes. We embraced his suggestion for creating new content through copying, combining, and transforming existing sources. We gave credit to those who inspired us and allowed ourselves to borrow and “try on” different styles, transforming them into something that was more our own. We talked about what we liked, what we didn’t like, what we were inspired by, and what we wanted to “try on” and transform. Inspired by Hanif Abdurraqib, we analyzed and borrowed the idea of creating meaning out of the form, craft and structure of a poem. We borrowed the idea of images as poetry in the works of artists like Tonika Johnson, Yvette Mayorga, Sentrock, and Gabriel Villa. We borrowed the literary techniques of Gwendolyn Brooks, Jose Olivarez, Eve L. Ewing, Nate Marshall, previous Garcia H.S. students, and, most importantly, the authors within the room.

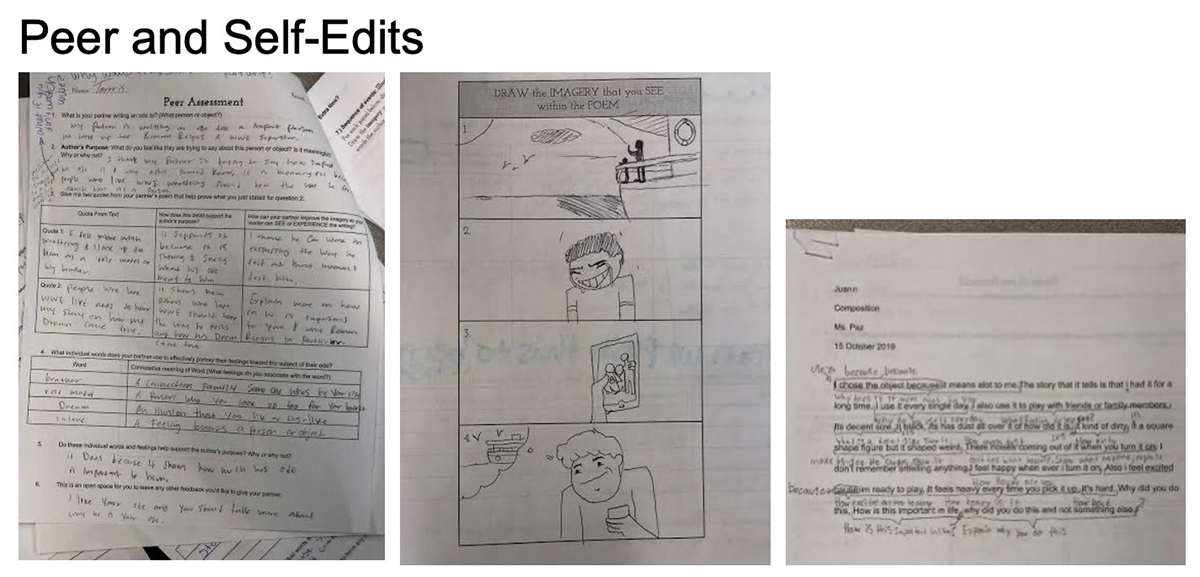

Allowing students to guide the conversation of what they liked and what they wanted to try transformed the classroom. Giving students time to have these conversations was invaluable. I witnessed more effort in their work because they knew there was an authentic audience on the other end of the assignment – their peers, not just me. Giving students time, space, and some structures to guide the conversations fueled their ideas. The best strategy (which sounds really cringy writing it now) was a lesson called poem speed dating. Students sat at a long table in the hallway and were given two minutes to read and write down notes about their partner's poem, followed by three minutes to talk about it. Authors at the same table taught each other, and they also taught me. There were many times we all said, “Dang, I wish I wrote that,” which gave us permission to “try on” each other’s ideas. One student compared the city to their teacher and explained what lessons it was teaching her: Lessons that she enjoyed and lessons that were harder to endure. This inspired others to create their own poems using the prompt, “Chicago as my teacher.” Another student wrote about how he used to read Harry Potter and believe in magic, “I used to believe in magic / I used to think that I was harry potter / I used to wear my glasses,” which inspired others to recall their childhood and talk about the magic they still believe in and the magic they don’t believe in any longer.

Conclusion

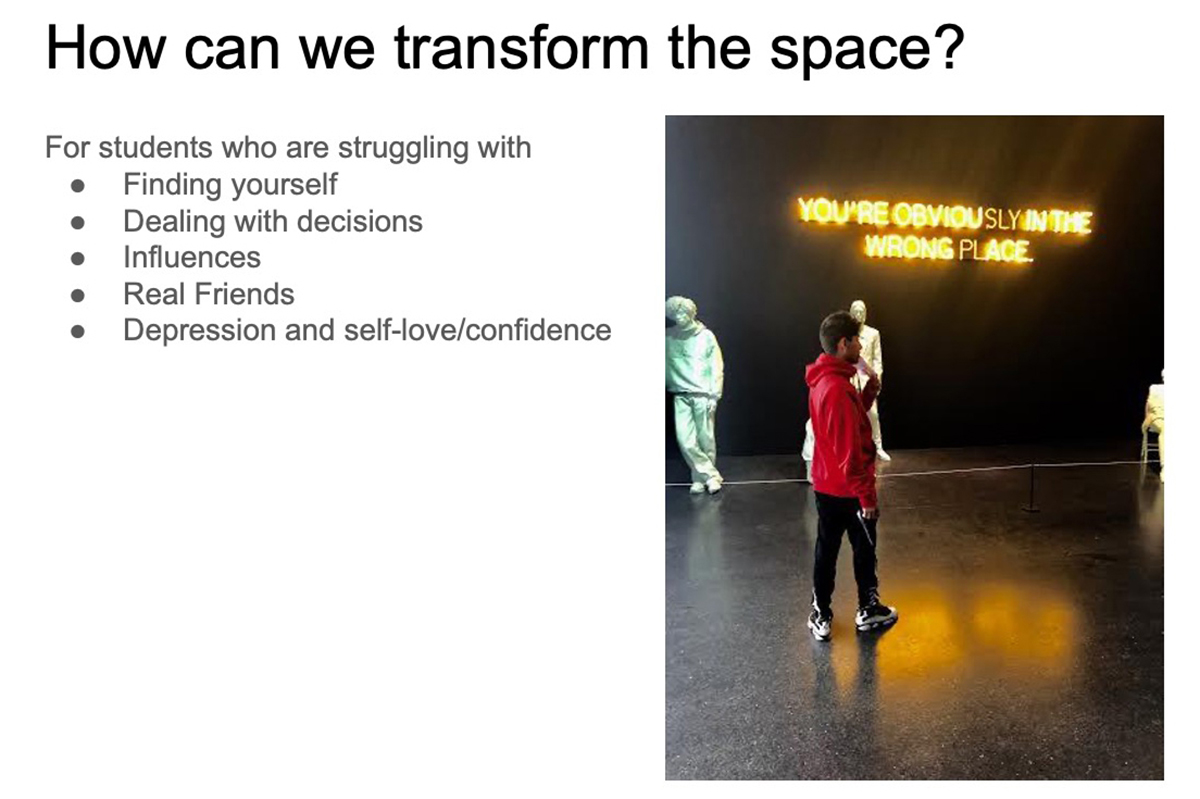

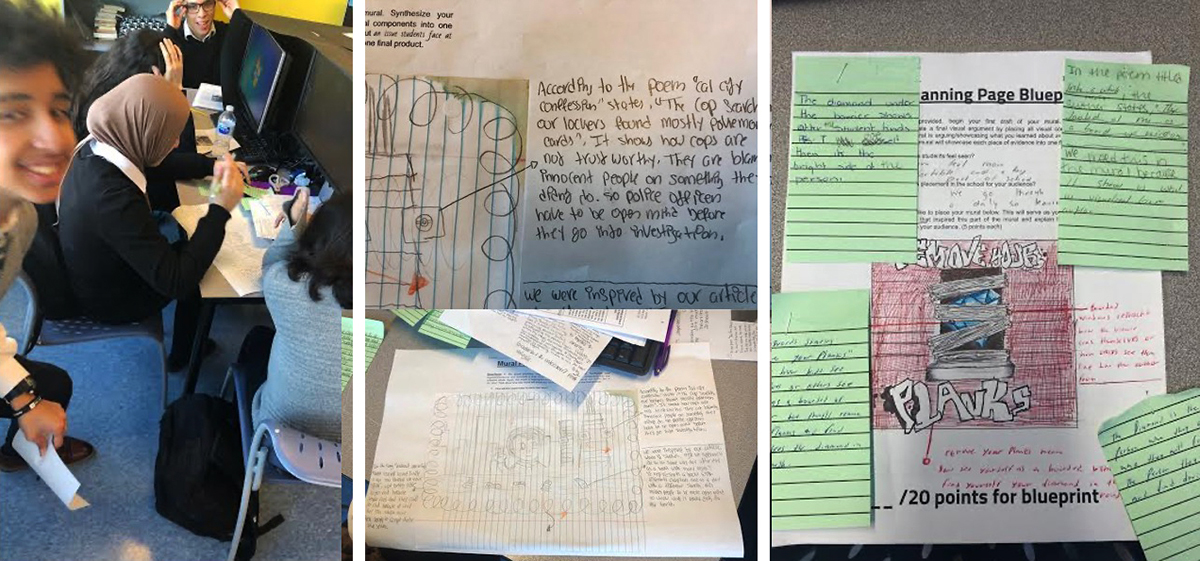

Students’ honest conversations sometimes led to roadblocks in their work, especially when they collaborated in groups in a space-transforming mural project. Some of the artists would disagree with each other, unable to see each other’s viewpoints or compromise. Students often felt pressure knowing their work would be shown publicly, with their reputation on the line for work they were not necessarily proud of producing. Some students were misunderstood and were deemed “hard to work with,” which pushed and tested their limits—and mine. Conversations that needed to occur beyond the classroom were productive, as deadlines were extended and extra time was spent after school. When asked what was important when collaborating with other artists, my students concluded it was how to listen and respond: “What are others saying? How are you entering the conversation? How can you remix your viewpoints into the community in which you currently exist?” We took these insights with us into our next projects.

Upon reflecting on this year, I’ve learned how to better collaborate with my students as authors and artists. Giving them the time, space and authority to act as masters of their craft is truly the best thing I have learned as a teacher. Although I am so proud of the work they have created this year, I am sincerely disappointed we weren’t able to remix, transform and create in other ways, such as in digital and group performances, due to the COVID-19 stay at home order. There is so much more I wanted to still show them, and I find myself asking, “How would they respond? What would they create? What would they teach each other and myself?” Despite the climate we are currently in, I am hopeful because of my students’ willingness to connect to each other and their ability to still be creative despite the hardships I know they are facing.

—Lauren

POEM SPEED DATING

Create a fun way for students to teach one another. Give students two minutes to read and write down notes on a partner’s poem. Then, give them three minutes to talk about it. Super-short time formats balance the high stakes of talking about another student’s creative work.

Lauren Paz

ACERO Major Hector P. Garcia High School

Lauren Paz is a reading specialist, living the dream as a high school reading and poetry teacher at ACERO Garcia High School. She enjoys coaching her school's Louder Than a Bomb team and helping her students publish their school's award-winning literary magazine. Education, social justice, literature, art, feminism, comics, and plants are all appealing to her.