Text-Based Paintings

By Joshua N. Hoering

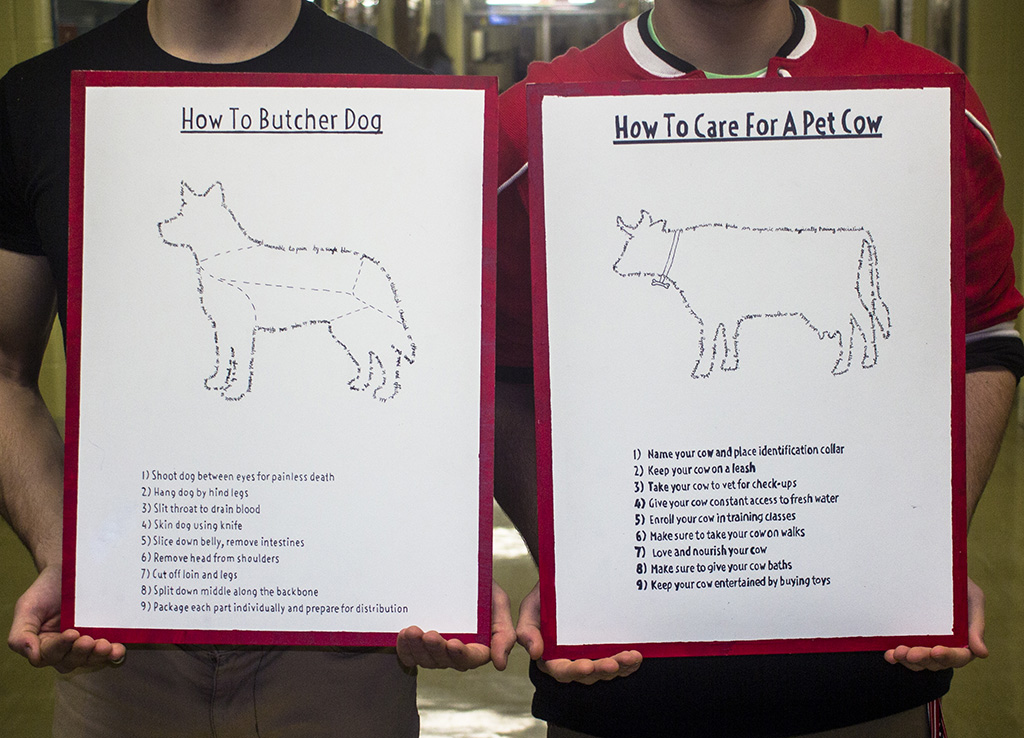

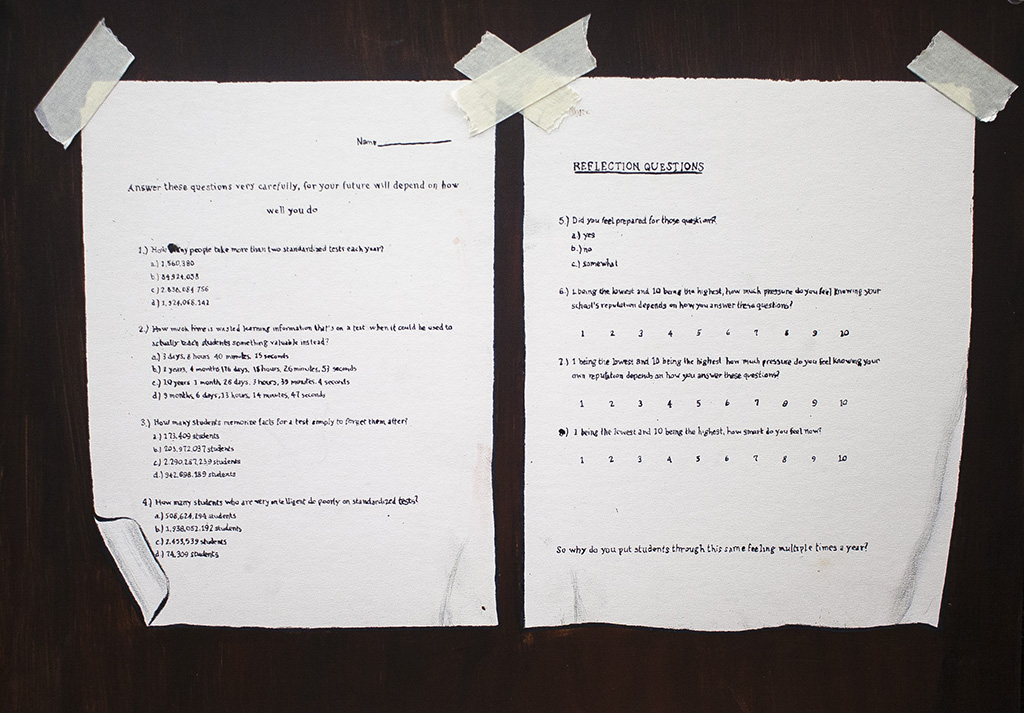

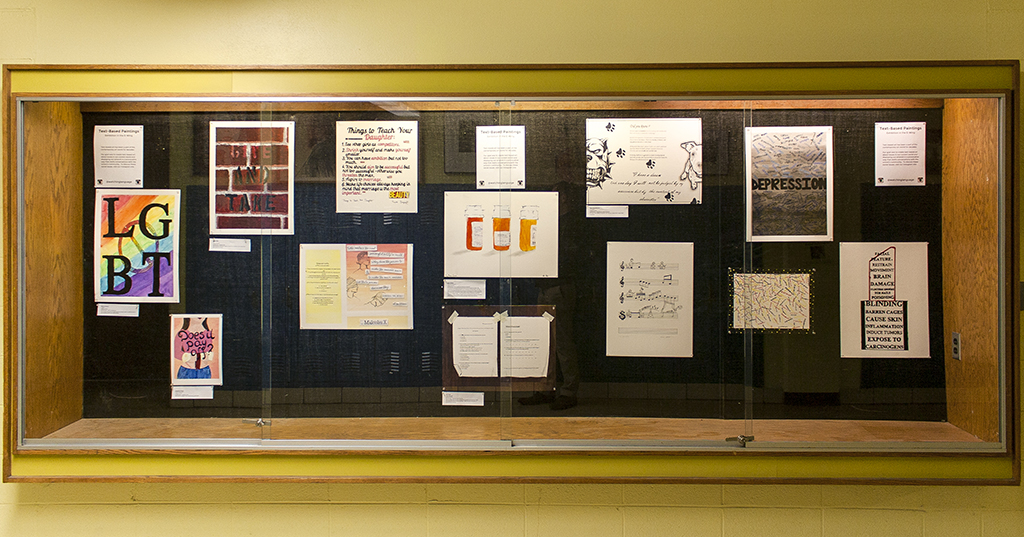

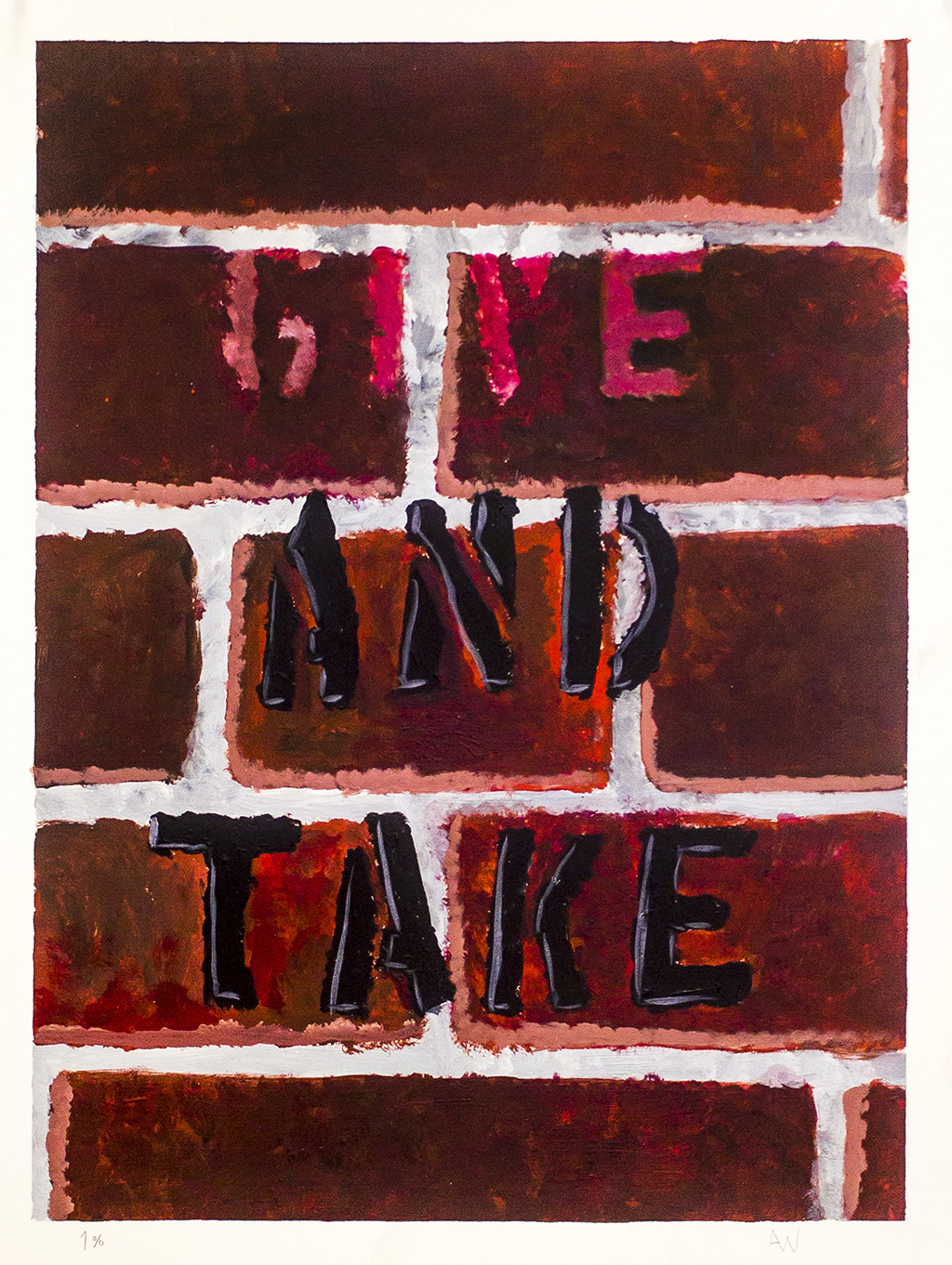

Students studied how text-based artwork has been a part of the contemporary art world for decades and looked at how it has been presented at the MCA Chicago. Our goal was to create text-based art about issues in contemporary society and then display the artwork in our school in a provocative yet accessible way that starts conversations with the school community. Once the artwork was exhibited, an interactive web app facilitated dialogue between student artists and the school community as a means of social engagement.

Goals + Objectives

- Students will explore ways that text in/as art can inspire conversation.

- Students will explore and exploit the possibilities of making text visual and physical.

- Students will reflect on and document their creative process and growth as artists.

- Students will present artwork in the school to start discussions and raise awareness of social issues with the school community.

- Students will utilize or develop an interactive web app to facilitate discussion with the audience.

Guiding Questions

- How does text function in/as art?

- What social issues are we most concerned about in today’s world?

- How can we learn different perspectives of social issues?

- How does presenting and sharing artwork influence and shape ideas, beliefs, and experiences in a community?

Documentation + Assessment

To record the creative process, students developed at least 5 different ideas for their projects, which were shared and discussed during critiques. Critiques were facilitated by the instructor, but were tracked by students using diagrams for analysis. Students were encouraged to take photographs of their artwork throughout the process, for sharing on social media and for personal records, and they photographed their finished artwork and wrote captions for the photographs for the collective project website. Students interacted with the school’s community by corresponding daily with people who left comments about their work online.

To reflect on the creative process, students wrote reflective statements about their experience creating the artwork. Students also had a summative critique to discuss their achievements and failures during the creative process, in the spirit of growth and collective learning.

To assess artwork, students collectively chose criteria for grading their projects at the beginning of the project. They set these criteria by analyzing contemporary text-based artworks and discerning the differences between successful and unsuccessful artworks. These criteria were made into a shareable resource in the form of a grading rubric. The grading rubric was filled out by the artist’s peers, themselves, and the instructor during critiques as a means of measuring feedback and to center the conversation on a common vocabulary. Throughout the project, the grading rubric was a flexible document, meaning that it could be changed based on students’ experiences, reflections, and discussions throughout the length of the project. The art department’s standard grading rubric was referenced throughout this process, as a means of ensuring that the project aligned with the students' and school’s quality expectations.

Timeframe + Learning Activities

Timeframe

- MCA field trip: 1 day

- Field trip reflection and discussions: 1 day

- Idea development and sketching: 2 days

- Formative critique: 1 day

- Project creation: 2 weeks

- Summative critique and reflection: 1 day

- Photographing and preparing artwork for display: 3 days

- Website development: 1 week

- Engagement with school community online: Throughout the duration of the art exhibition

Learning Activities

At the beginning of this project, students brainstormed independently and in groups about raising awareness of key issues, considering different perspectives on those issues in society. A worksheet helped to facilitate this portion of the project.

Students determined an issue for closer focus and sketched out their plans for projects, creating at least 5 sketches in order to practice divergent thinking and build confidence in making final decisions for projects.

To facilitate a formative critique, one student tracked a large group conversation about the proposed content and execution of the projects. This student used drawing to note other students’ behaviors while the teacher asked overarching philosophical questions to the group, literally drawing connections between students and their ideas. The drawing that the student developed while tracking the conversation was then shared with the group to start a conversation about discovered patterns, commonalities, and behaviors from the group’s interactions. Students then shared assumptions about what each student’s artwork intended to communicate, encouraging a collective dialogue about the importance of clarity and its impact on audience interpretation of the artist’s intentions.

Students could use unlimited media to create the visual artwork, an openness that encouraged the possibility for materials to specifically contribute to the artwork’s meaning or message. Small group critiques were facilitated regularly to encourage students to share and build ideas collectively. These critiques were instrumental in refining artworks, but they also offered opportunities to discuss and learn from failures.

As a means of reflection, students wrote one paragraph about the artwork itself, one paragraph about their experience creating the artwork, and finally a caption for the website. Captions included facts, questions, explanations, and experiences related to the student’s chosen social issues to encourage dialogue with the school’s community.

Artwork was photographed and prepared for physical display and then posted to the mobile app with captions, which opened up a gateway for students to discuss artwork and ideas using a smartphone or computer. The exhibit at the school included QR codes, which could be scanned with cell phones for efficient access to the online dialogue about each individual artwork.

After the art exhibition concluded, students utilized the mobile app for the remainder of the year as a tool to engage with the school community about the issues presented in future art exhibitions.

Materials

- Idea creation: Worksheet and pencils

- Drafting materials: Sketchbooks, pencils, rulers, and access to font print-outs

- Painting materials: Illustration board, acrylic paint, brushes

- Exhibition: Mat board, exhibition posters, camera, and website

MCA Connections

Inspiration for this project came from a field trip to the MCA’s Freedom Principle exhibit, which was on view in Fall of 2015. The exhibition featured African American experimental artwork from the 1960s. During the field trip, students reflected mostly on the text-based works by Glenn Ligon, Nari Ward, and William Pope.L. Their concepts were immediately accessible and provoked memorable conversations among students. Those conversations became the starting point for our creative investigations using text to provoke dialogue around social issues.

References + Resources

- Glenn Ligon. Give us a Poem, 2007. Black PVC and white neon. 75 ⅝ × 74 ¼ in. (192.1 × 188.6 cm). The Studio Museum in Harlem, gift of the artist.

- Nari Ward. We The People, 2011. Shoelaces. 96 × 324 in. (243.8 × 823 cm). In collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

- William Pope.L. Another Kind of Love: John Cage’s Silence, By Hand, 2013–14. Yellow legal paper and dyed wood lattice. 220 sheets, each: 8 ½ × 11 in. (21.6 × 27.9 cm); overall dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash.

Joshua N. Hoering

Maine Township High School District 207

Joshua N. Hoering has been an arts educator for over ten years and is based in Chicago, where he teaches at Maine Township High School District. He directs community projects, hosts professional development seminars, organizes art exhibitions, and is a visual artist. He holds a Master of Science in Education and a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Indiana University.

Before becoming a classroom teacher, Joshua worked with the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP) to research the results and effects of arts education on alumni of high school, undergraduate, and graduate level programs. Along with being a teacher, Joshua is the Portfolio Coordinator for the Illinois High School Art Exhibition (IHSAE), which has connected students in Illinois to over 55 million dollars in scholarship offers. He also serves as a Visual Arts Advisor for the Illinois Arts Learning Standards Initiative to produce recommended standards that reflect best practices in arts education.

Joshua reflects on his process:

The key to success in this project was putting students at the center of the creative process from the beginning and having them guide the creation of the project while I supported their ideas. When we visited the Museum of Contemporary Art, I didn’t know what kind of artwork would be made or how students would respond to the Freedom Principle exhibition. A central idea in the exhibition was improvisation, as it related to jazz and experimentation in art and music. I decided to take the improvisation approach with my students by learning which artwork drew students’ attention and inspired their favorite conversations to find the best starting point to develop a project together.