(In)visible: A Project on Equity

By Michael Ho

(In)visible, A Project on Equity, was an art project done by the 69 fourth grade students at Willard Elementary, a small neighborhood school serving 300+ students located in the community of River Forest. The impetus for this project comes from my lived experience as a Vietnamese American educator working in a predominantly white (non-Hispanic) work environment and how one navigates and makes their voice visible in such an environment, one that at times can seem familiar yet foreign. From my experience as a working artist and educator, I understood that one way that my students and I can make our voices and thoughts visible is through the production of art. Since my hiring, District 90 and Willard school have made educating our students, staff, and community about the importance of equity a priority. However, it seems that student voices were not a part of this conversation. Thus (In)visible, A Project on Equity, was born.

(In)Visible is a conceptually oriented art project that had students engage with the concept of question of equity, explore how it affects their lives, and create an artistic response to their question. The three primary objectives of this project are:

- To invite students to explore the concept of equity through their own interests.

- To create works of art that focused on an idea or concept rather than aesthetics.

- To facilitate an opportunity for the students to become aware of how their art can interact with their school community.

To guide my students and myself through this process, a few key questions were devised. When writing out these questions, an effort as made to avoid questions that would result in a quick yes/no response. Instead, the questions devised for this project resulted in some interesting and insightful conversations. The questions which guided this project were

- How have you felt inequity in your life?

- How does it feel to be treated with inequity?

- What are some potential ways we can talk about the inequities you have experienced?

- How do we reveal them and/or address them?

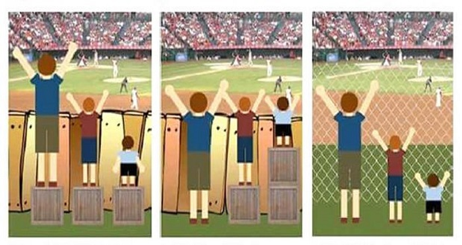

(In)Visible was done with 3 4th grade classes, with about 23 students in each, over the course of a month and a half or 4-6 one hour art sessions. This could vary depending on the size of the classes and the equity topic they choose to explore. We began the project by having a group discussion about equity and what the word meant. Afterwards, the knowledge gained through conversation was then used to analyze graphics, culled from the internet, about equity.

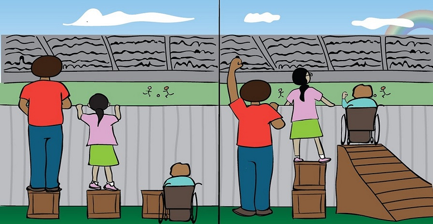

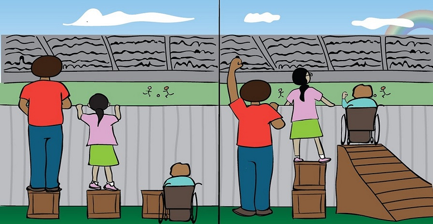

As an individual with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 3, a neuromuscular disease, I leaned more towards the second graphic you see here, since it is something I could speak to. I would suggest finding an image that your students and you could speak to. After analyzing the image, it felt important to provide opportunities to have students share anecdotal stories about an inequity they have felt in their lives. I offered to go first and shared my childhood experiences of feeling inequity. I did this not only to model the behavior and respect I would like to see with my students, I did this to allow myself to be vulnerable to my students. I ask students if they would like to volunteer but never require them to share if they do not want to or are uncomfortable.

Following this discussion, I asked students: How do you think art could be used to talk about inequity, and what would that product/action look like? After a brief discussion, I then showed my students the work of William Estrada, Maria Gaspar, and Mel Chin. It’s important to also note to the students that William Estrada and Maria Gaspar are Chicago-based contemporary artists to spark inspiration. Afterwards, the students, working independently or in groups, spent the rest of the day to plan their projects. Teachers can choose artist exemplars within their community who are also working with the concept of inequity.

Throughout the next few days I encouraged my students continue to work on their projects. Prior to letting them work on their projects, I would introduce them to other artists working with the concept of inequity to prompt conversation and to model how different artists address inequity. This was done in response to the type of work that each class was producing. The artists used during these mini-discussion were Olafur Eliasson and Doris Salcedo. Throughout the next few days, students continued to experiment with different ideas and the limitation of their chosen art materials. While the students were experimenting with their ideas and materials, I was experimenting with finding a flow or harmony between providing enough guidance without coercing the students into making something I would make. During this period of the project, the concept of “Energy, Yes. Quality, No.” (often uttered by the artist Thomas Hirschhorn) became a constant reminder that these are the students’ projects, and that I should be careful to not exert my own aesthetic sensibilities onto them because they appear to “child-like” to me.

Following the students’ completion of their projects. I allowed students to explore different ways of presenting their work. Some students, whose work were more 2D in nature, were allowed to scout locations for their pieces to be displayed. While other students, those who had more participatory pieces, explored different ways of presenting their work that might or might not use the wall. An example of this is a bound book composed of responses to a form which asked students how they could treat each other nicely. The project officially concluded after 5 art sessions with a group discussion and presentation of work. Later in the year, after some coordination with the 4th grade team and their schedule, we took 3 sections of 4th grade students to the MCA.

Striving for a Student-Led Experience

In the previous section, I outlined the bigger gestures that guided the project. The following section will explore how I allowed In(Visible) to be student led. Since many of us struggle to achieve a genuinely collaborative environment at the elementary level, I offer these insights into our processes, including the challenges of finding harmony between student led projects and teacher guidance.

Which issues matter to our community?

After the project’s introduction and discussion, I allowed the students to split up into groups and discuss what issue, framed by the concept of equity, they wanted to explore. Prior to allowing the students to begin work on their projects, I asked them questions such as, “how does your project explore equity?” as a way to quickly assess their progress and to see if they were stuck. When the students were able to articulate what they were doing, I would then provide them with the materials they needed to execute their ideas.

Listening, watching, responding

When the students were planning and sketching their projects, I tried to notice what each class was doing and how they fed off each other. I adjusted the week’s activities based off of my informal assessment. An example of this is the introduction of artists Olafur Eliasson and Doris Salcedo in mini-discussions responsing to elements I saw in their works in progress. In addition to providing my students with more exemplars, the inclusion of these artists also worked to encourage Willard students to consider other approaches to meaning-making.

Their art: traditional and socially-engaged

Willard students made a variety of projects. Some artworks functioned as a traditional 2D piece, while others, such as the Tree of Strong Women and Willard Students do the Golden Rule require students and community participation in order to be activated. In the case of the latter, the piece could only function by 1) having the school community complete a questionnaire about how to treat one another, and 2) having the forms submitted, compiled, and bound into a book that is now on view in our school library.

The realities of documentation

Since last year, Willard began making a push to use Seesaw to document their working process. We are still trying to experiment with different workflows to see what works best. The students have been pretty good about reminding me that they want to take pictures of and talk about their work. However, a challenge has been managing student portfolios as a co-teacher. With the amount of work that gets completed in art, I found it difficult to find the time to authorize all the students’ posts in SeeSaw (Willard’s learning portfolio management system). When I didn’t go through on a routine and daily basis to click “accept” on the student’s posts the resulting backlog of posts waiting to be approved became overwhelming for the co-teachers who also used SeeSaw to document their students work. I am now exploring other options of maintaining student portfolios separate them from their homeroom class SeeSaw portfolios.

Rethinking authentic assessment together

I wanted to have the students discuss how clear their message was and whether they felt the project accomplished the goal of sharing this message. Since this project focused more on the concept rather than the aesthetic, it would have seemed counterproductive to grade the work on a criteria such as craftsmanship. Since every project is different in some capacity, the students and I felt it would not be “fair” to grade the projects based on that criteria. So instead we assessed how well the project communicated their message and whether the project unfolded the way they intended. Much like previous parts of this project, Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Energy, Yes. Quality No.” functioned as its touchstone and as a reminder of what the purpose of this project was.

Materials + Supplies

- A variety of art materials, responsive to student interest: pencils, color pencils, markers, permanent marker, tempera paint, watercolor paint.

- A variety of paper. 12x18 90# sulfite, 18x24 90# sulfite, and watercolor paper.

MCA Connections

The MCA served as a great resource for Willard students and the field trip left a lasting impact on them. I will mention that the logistics of coordinating 3 grade level teachers and finding a good date for all 3 teachers for their trip to the MCA was a valuable learning experience. I can see how this might be discouraging for elementary teachers who may teach several sections of 1 grade level. If given the opportunity again, I would have preferred having the students go to the MCA at the beginning of the year to set the tone.

Even though I did not use much of the artwork from the current exhibitions at the MCA as exemplars, I did incorporate previous MCA exhibitions, such as Doris Salcedo, through our group discussions. Furthermore, without the MCA as a resource I may not have become aware of the work of William Estrada and Maria Gaspar, two Chicago-based artists I used as exemplars in (In)Visible.

References + Resources

- Thomas Hirschorn - Energy, Yes. Quality, No.

- Olivia Gude — Principles of Possibility

- Olivia Gude — New Art School Styles: The Project of Art Education

Michael Ho

Willard Elementary

About Michael Ho

Michael Ho is first and foremost a human being filled with hope, ambition, curiosity, and a healthy amount of reservation and suspicion. His personal characteristics possibly stem from his upbringing as a child of immigrants who fled their home country of Vietnam in 1975. Growing up in the early 1980s, Michael never felt like he socially fit in with his peers. He tried many things to fit in, but they just didn’t feel right for him at the time. Then in 1998, a chance encounter with a friend in high school and a stint at a summer pre-college art program at RISD helped Michael rediscover and reignite his passion for art. For Michael, art would become a lifelong outlet for him to explore and rediscover his identity.

Just when Michael felt everything was in its right place, his physical health began to change. Around 2003, he was diagnosed with SMA (Spinal Muscular Atrophy) III. Working as an art installer, a field of work that requires a bit of physical strength, Michael realized he had to find a better way to sustain himself. Therefore in 2005 Michael started his teaching journey. Since then, teaching has allowed Michael to live a fairly happy life and it has allowed him to travel to Oaxaca, Mexico, and throughout Vietnam. Teaching has also provided him with a reason to go back to graduate school in 2014 for a Masters in Art Education at the University of Illinois. Currently, Michael is striving to find work/life harmony rather than balance. He wants his work and life, teaching art and making art, to become integrated rather than two parts of his life that struggle for his attention.

Michael Reflects on the Project

Prior to the MCA Teacher Institute, I have often thought about facilitating a project such as this, but was afraid to because of a lack of resources and support. Through the support of the MCA and the Teacher Institute fellows, I was able enact the project I proposed, learn from it, and now through the next few paragraphs reflect on it. Even though the project went off without a major hitch, there were a few lessons I’ve learned throughout the course of this project. However, before I explore some of my hallelujah moments, I first want to reflect upon some of the obstacles that I encountered during the course of this project.

The first challenge I encountered was that of culture and time. Coming into a new school, I first had to grapple with a different artmaking culture. After working at Willard for a year, I thought that by the second year the school would have experienced a more significant shift in its artmaking culture. This project reminded me that even two years is not enough time to experience a radical change. For example, I realized that my students had some difficulty generating ideas for their (In)Visible possibly because they were still used to doing projects that are teacher-led and where ideas/solutions are teacher generated rather then student generated. In response to this, for the following year, I want to restructure the curriculum for my classes so that there is a greater emphasis on understanding the different ways artists can generate ideas for their projects. By doing this next year I hope to model to my students how artist are inspired while also providing them with a possible framework for thinking and creating.

Another challenge of (In)Visible was acknowledging and checking my assumptions about power and privilege. As an art teacher of 13+ years, I have become more aware of the power I hold as the arbiter over what is deemed as quality work. With each passing school year I have become more sensitive to how my words and interactions can affect students’ perception of their own work. In a way, I have as much power as a museum curator, if not more, in determining what works hold cultural weight and power. It is my goal as an educator to help my students develop their own aesthetic sensibilities and courage as makers. Therefore, I had to “tap the brakes” with regards to my own perceptions of what constitutes as quality work. When I allowed myself to let go and allowed the students to explore meaning making, I really enjoyed the work my students were making and the student’s as a result enjoyed what they made. The challenge for me is finding harmony between providing enough freedom and choice without burdening my students with too many choices. However, I feel that a good reread of Olivia Gude’s New Art School Styles and Principles of Possibilities will help me along this journey.

At the same time, many beautiful moments that came out of this project. One beautiful moment happened a month or two after the projects were displayed in our school. Inspired by, what I presume, is the participatory nature of (In)Visible’s projects, I began seeing poster made by students from other grade levels, who did not participate in this project, appear outside of several classrooms. Witnessing the “viral” power that participatory artwork had on my student, I have become interested in designing projects or experiences that allow my students to engage with this form of meaning making. Other moments that arose—which were neither aha’s nor challenges—were:

- Noticing the level of student engagement when students lead their own projects.

- Understanding that student led projects ask the educator to be nimble and flexible.

- Time is a slippery thing, and the pressure of working in blocks can sometimes feel a bit overwhelming.

- Each class needed different resources and/or scaffolding.

- Projects that are more participatory in nature needed more explicit instructions for student participation, and other, more durational projects can rely on the student for maintenance.