Contemporary Questioning

By Jequeline Salinas

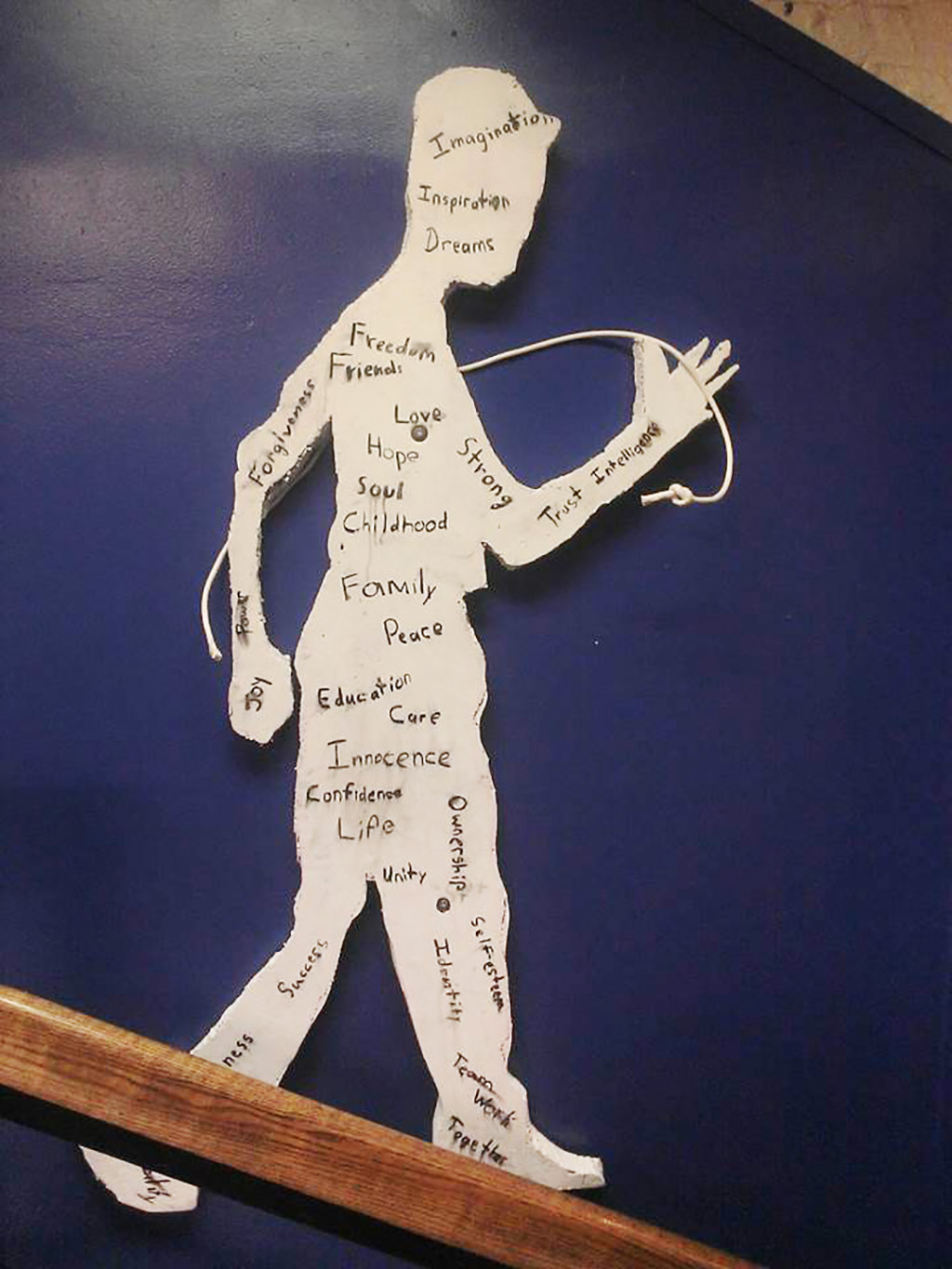

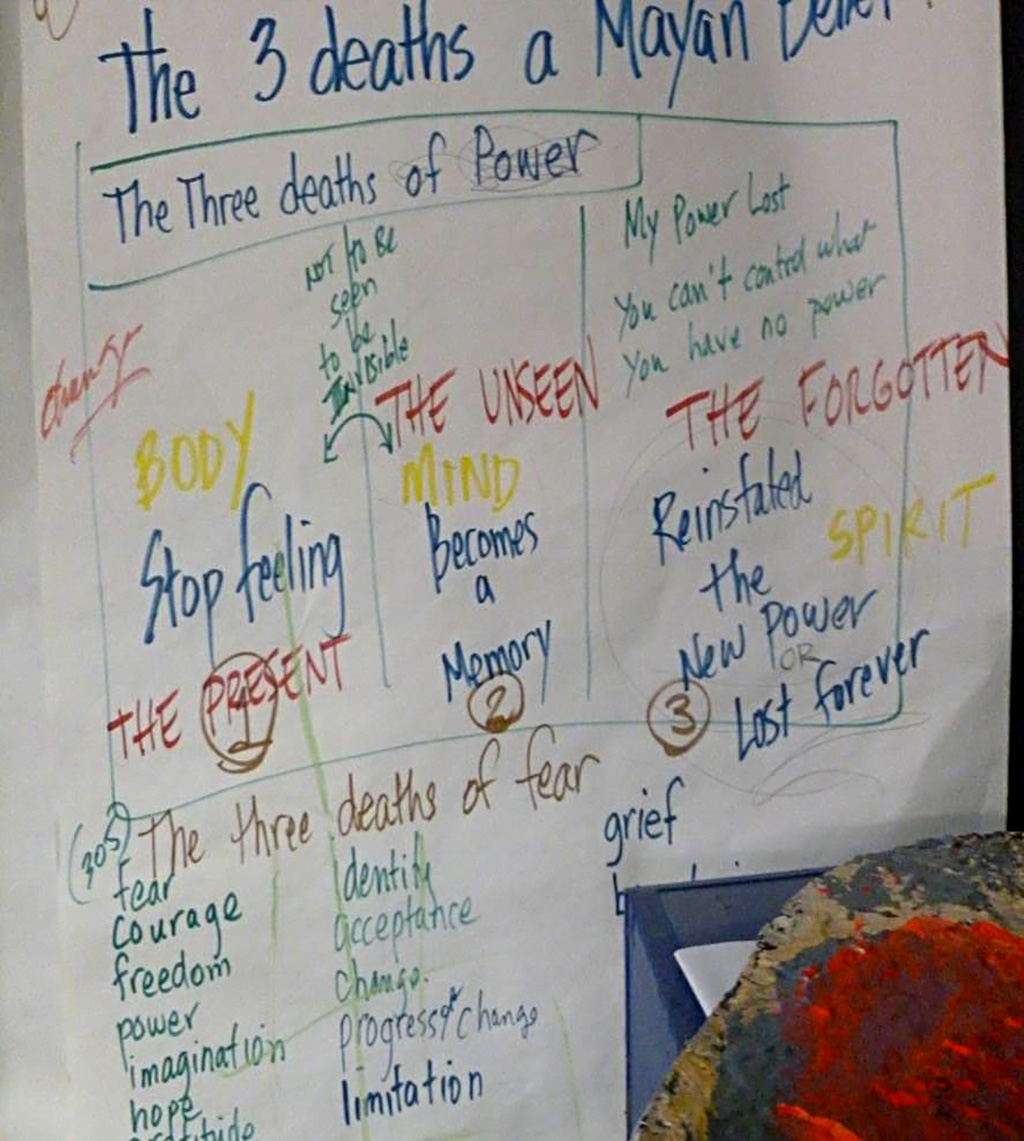

The students used the ancient Mayan belief in three deaths as a springboard to create a teacher/student dialogue about the way one can creatively frame death. The students discussed their own cultural understandings of death and drafted new concepts of the stages of death that paralleled the three deaths, generating big ideas to bridge these cultural connections while igniting inquiry about contemporary society, personal perspectives, and narrative.

Goals + Objectives

- Students will explore how art can communicate a story through discussions, while using a variety of references that lead to creative thinking, writing, and storytelling.

- Students will learn to develop big ideas as they reflect on cultural beliefs and imagine and interpret meaning for contemporary issues.

- Students will discover how student voice can be honored, and understand that their lived experiences, curiosities, and views on societal problems can become the platform for the research and investigation of art themes.

- Students will utilize space to create art installations strategically.

- Art students will learn to observe and listen to the audience responses. Art students will document and reflect on how well the art Installations affect the individual or the community as intended.

- Students will analyze how art can shape the understanding of social issues.

Guiding Questions

- If you could visualize each one of the three Mayan stages of death, what would each look like?

- Can you now take one stage and make a comparison to a feeling you might have experienced? What word can best describe that feeling?

- If you could re-imagine the stages based on these feelings, how would you develop a new meaning or concept for each stage while maintaining the parallel connection, thought, or feeling? Develop a story based on this re-imagined meaning or big idea.

- What in your story or big idea connects with your life? Is it a lived experience? Is the story true to your personal life?

- How can you explain the use of the materials, objects, or imagery with the story? Describe the connection.

- Does the space that your art team selected for the installation enhance the meaning you intend to communicate?

- What scale is appropriate for the space?

- In what way do you want the audience to interact with your installation? Do you need the audience to interact with your artwork? Are you comfortable with this happening?

- How will we know if other students and audiences are reacting to the artwork?

- How do artists use a cultural belief such as the Mayan three deaths to inspire contemporary art?

Documentation + Assessment

What did the students do to record their process?

The students generated a brainstorming chart to recreate meaning for the Mayan cultural belief that served as the springboard. The students drafted stories using their own lived experiences. They created sketches to plan the artwork, took pictures of the process, and participated in video interviews about their projects.

What did the students do to reflect on/assess their process?

The students allotted time to interact, discuss, and participate in ongoing critiques during the process. Students asked for clarity and assistance from their peers, made observations of the audience reactions to their work, and modified their work based on audience and peer feedback.

Timeframe + Learning Activities

Timeframe

Each day equates to a 60-minute session.

- Day 1 — Introduction

- Day 2 — Generating Student Voice

- Day 3 — Collaborative Discussions

- Day 4 — Field Trip

- Day 5 — Selecting a concept

- Day 6 — Contemporary artists

- Day 7 — Art Installations

- Day 8–9 — Preparing Art Gallery

- Day 10–12 — Engaging the Public

- Day 13 — Audience Response

- Day 14 — Reflect and Move Forward

Learning Activities

- Introduce students to a cultural belief and create the springboard for generating new concepts and big ideas. Provide students with time to dialogue, analyze, and respond to this cultural belief. Present and discuss the meaning of contemporary art. Create an anchor chart to graph the original three stages of Mayan death. Start the ME/WE Experiment, inspired by Glenn Ligon’s ME/WE piece (Give Us a Poem) in the MCA Chicago’s Freedom Principle exhibition. In this experiment, students intervene on campus by cutting out text and taping it to the walls around the school building in unusual places, while also keeping this action secret. Create an assignment for students to record the reaction from their peers.

- Generate student voice, ideas, and the project format along with correlations to the Freedom Principle exhibition at the MCA Chicago. Students take a field trip to the MCA Chicago and are inspired by Give Us a Poem by Glenn Ligon.

- Collaborative Discussions: Students dissect the original stages of the cultural belief and re-imagine the stages into three categories, developing new concepts based on these categories.

Students select a concept and a big idea, and then draft a story. Students have conferences with the teacher for feedback and guiding questions. - Review other contemporary artists focused on socially engaged themes. Revisit and revise story-writing, construct collaboration teams, and create material lists and sketches to plan art installations. Take videos and photos to document this process.

- Students participate in hands-on activities and reach a consensus about art installations.

Prepare the Art Gallery for the installation by recruiting parent and student volunteers. Students continue creation and construction of artwork. - Draft a plan to implement ME/WE school-wide presence in the learning environment. Embed the ME/WE concept into school-wide expectations and Art Studio Rules. Create a classroom ME/WE wall, which is a collaborative art installation that reflects the private identity and public identity of each student. Students finish art installations.

- Capture audience responses through dialogue and an open invitation to modify art installations if needed. Write artist statements for gallery labels.

- Reflect on audience response. Use the feedback to generate new project ideas for the next project, focusing on Socially Engaged Public Art.

Materials

- Rigid 1.5- and 2-inch thick insulation

- Acrylic paint, markers

- Found objects

- Gesso, primer

- Scissors

- Brushes

- Masking tape, duct tape

- Vast variety of found objects

- Sand

- Fabric

- Plastic tubing

- Nails and a hammer

- Colored sheets of paper

- Camera

- Lettering templates

- String

MCA Connections

Thirty-five students participated in a field trip to the MCA Chicago to see The Freedom Principle. The students participated in a guided tour and learned about the exhibit. The ME/WE artwork by Glenn Ligon (Give Us a Poem) became a focal point for students to analyze and explore the concept of individuals in relationship to the community. Other works that inspired their thinking perspective were We the People by Nari Ward and Speak Louder by Nick Cave.

References + Resources

- Naomi Beckwith and Dieter Roelstraete, eds., The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

- Speak Louder (2011) — Nick Cave

- We The People (2011) — Nari Ward

- Give Us A Poem (2007) — Glenn Ligon

- Project Excerpts, 96 Acres — Maria Gaspar

- JR Art

Jequeline Salinas

Hedges Fine and Performing Arts School

Jequeline Salinas is the visual arts teacher at Hedges Fine and Performing Arts School, a PreK-8th Grade Chicago Public School located in the Back of the Yards Neighborhood. She earned her B.A. in Art Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1995. Jequeline was born and raised in the Pilsen Neighborhood in Chicago. She has been the recipient of many grant awards throughout her career, from the Chicago Foundation for Education, Illinois Arts Council, Oppenheimer Family Foundation, and more. At her core lies a deep passion to help young students learn the language of the arts, while instilling the realization the power of this language to problem-solve, create change, and build logic and reasoning across subject areas. She strives to awaken the consciousness and sensibility of her young learners through their own personal journeys in learning about life, society, and the complexities of growing up in a bicultural setting. Embedded in her practice is the presence of community-building and honoring cultural perspectives. Her reflections and knowledge about her students' everyday lives and challenges provide her with ongoing opportunities to explore and expand on identity, personal perspectives, society, and culture through critical inquiry.

Jequeline reflects on her process:

This project honored student voices, and their interest in telling their story became a platform for understanding how artists can shape the understanding of social issues and student perspectives. All of the art installations considered how the audience would develop an understanding of the topics, make connections, and ask questions. Participation in the project was school-wide: both the adults and the students interacted with the work. Student voice, their stories, their feedback, and their creativity were honored.

Each art installation created buzz for the student artists. Parents supported the LGBTQ-topic pieces in spite of initial worries about parent objections. The parents became enthusiastic about the culminating art exhibit, and invested their time in painting the gallery walls. It was amazing to witness how students created new ways to think, produce art, and explore concepts.

One major obstacle was an abrupt change in administration at my school. I questioned whether I could continue with the scale of the project and maintain autonomy to create my curriculum. I addressed it, and found that the opportunity to partner with the MCA Chicago was a positive force to sustain this project.