Art as an Agent of Community Healing

Students confront internalized violence through storytelling and performance.

By Mauricio Pineda

This project was born from need. After listening as a 5th grade student shared with me a story of a crime committed in front of him—his reaction: take a picture and post it on Facebook, and his definition of this crime as a “clean one” (no blood was seen around the location, in comparison to some others he has encountered)—I realized that in this neighborhood, violence has been internalized. Therefore, there is nothing like an art project to bring awareness about the way students see their lives within these environments.

Reilly Elementary School, where I teach, is located in the heart of a troubled neighborhood and its community is made up of low-income members. The idea behind the project is to have students confront these issues directly, rather than having them continue to be the background to their everyday lives as the “norm.” By default, this also affects the community at large by helping bring to light this dichotomy—embedded acceptance of violence and conflict, versus empowerment to seek out proactive solutions.

In order to guide this encounter of reality with introspection and honest expression, my students and I explored these questions:

- What is the role of art in our community/society?

- How can we recognize the need for action?

- What is worth knowing?

The project must grow organically as we gather information, do research, collect testimonials, take pictures, sketch ideas, collect objects, etc. around the issue of violence in our community. Once we have gathered all this information, students work in groups to create a series of artworks that address their take on the problem of violence. Students then take charge of their own projects, developing their art pieces in a way that is most relevant to their observations and allowing them to best communicate their ideas. These artworks might include video, sound, found objects, painting, drawings, collage, etc. Throughout this experience, scaffolding is put in place in earlier lessons through learning about contemporary art and artists, as well as exploration of different material and media to learn what each of these elements can express, thus arming students with enough prior knowledge to address the theme of this project successfully as artists and thinkers.

- Transforming the community from within rather than from outside—no use of prescribed solutions that aren’t relevant to this community.

- *Use contemporary practices and artistic approaches as a tool for reflection and action, oriented to change.

- Objectify a situation: Treating facts/situations as malleable objects that can be subject to change.

Documentation + Assessment Suggestions

Most of the assessment had to do with keeping up with the timeline and the active participation of students. There was a lot of communication between me and the groups to discuss projects, as well as to identify the roles of each student in the making of the work. Finally, students wrote a statement explaining their process and work along with self-assessments that were formally handed into me—prior to this, students had a conversation about what they valued in each group member and came to a consensus in terms of the final grade. We documented most of the process with videos and photographs—in retrospect, I wish I would have had the opportunity to have students journal.

Learning Activities

Engage in talking circles to recognize violence, its meaning and implications:

- Students and teacher gather in a circle, everyone seated at the same level.

- Teacher introduces an object that will be used as the “talking piece.” The object must contain personal significance to the teacher/circle keeper.

- Teacher/circle keeper must share the story of the object, why is it important to him/her?

- Rules of the circle are set: whoever holds the talking piece has the power of sharing, the ones without it have the power of listening.

- The talking piece must be passed around the circle in order. If a student chooses not share it is OK, all he/she has to do is pass to the next person.

- The first question must be an icebreaker to try out the system (for example: If you could have a superpower what would it be? What is an animal that represents you? What is your favorite home meal?)

- Now we can dive into deeper questions using the same system. In our case we ask: How is life around the neighborhood? Have you experienced or seen an act of violence? What is violence? How often have you witnessed it, or how often does it occur? How do people respond to it?

- After everyone shares and has listened to their stories, and it is evident that we became closer, the circle finishes with a check-out question. (i.e. How are you leaving this circle? In one word describe how are you feeling right now? What did you learn from today’s activity?

Record interviews with one another to learn about our personal experiences:

- Students turn to share stories in small groups. There are designated recorders who navigate from group to group, collecting these conversations on a sound recorder.

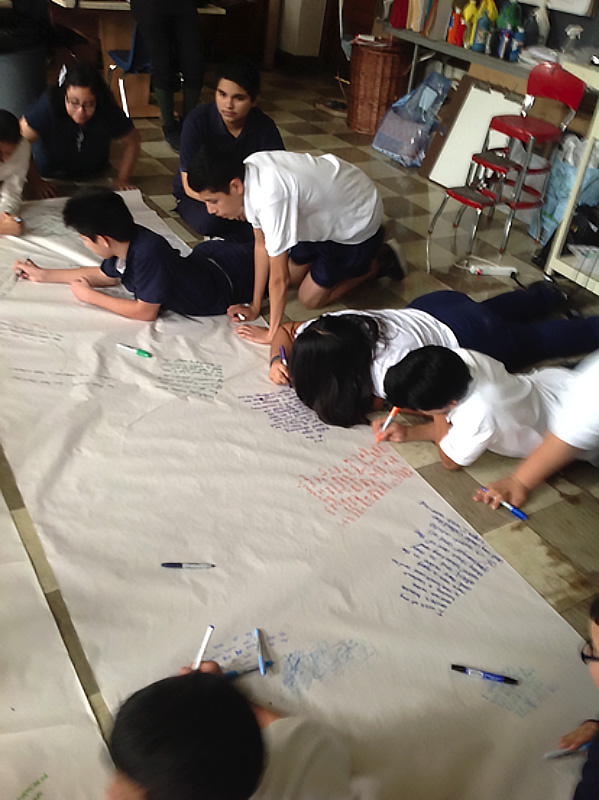

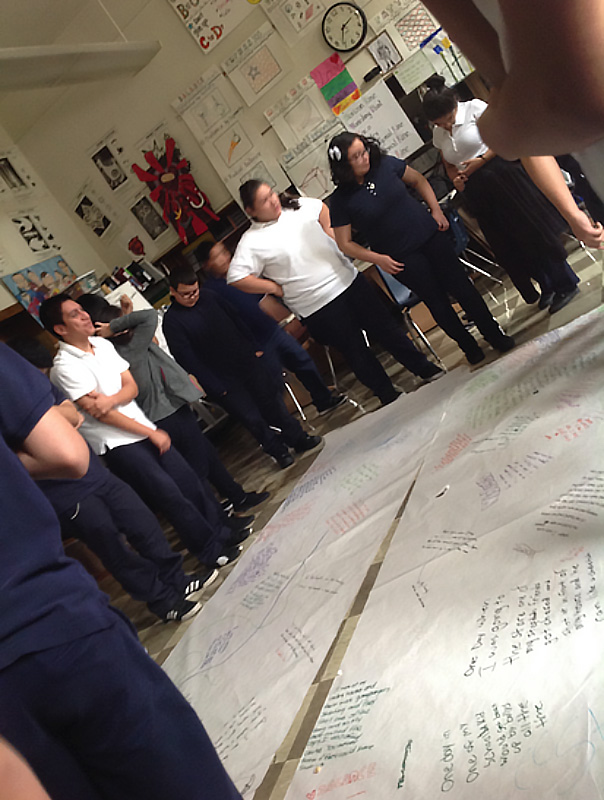

Write down all stories on paper board to then identify and connect similarities among them:

- Students walk around the paper reading and making connections among stories using markers.

Use Theatre of the Oppressed techniques to explore the effects of violence in our overall energy, body language, mindset, etc. One example of an activity:

- Students impersonate stories as they were written, silently, but making body language extreme.

- Students must move backwards from the moment where stories took place to the past. If you were the aggressor or victim, what happened to you before and after the scene?

- Students debrief: Why did you think that happened before or after?

How did you feel your body reacted: tension, muscle contraction, breathing? - Replaying scenes in slow motion with a positive outcome (not the same as a happy outcome).

Plan a Field trip to the MCA focused on expressing ideas in non-literal forms.

- In my case, we were able to come to MCA to see Simon Starling’s exhibit, Metamorphology. His work inspired students to redirect their efforts toward more introspection, toward more analysis of how to tell stories through their work in a way that differs from sensationalism and literalism. We were able to talk about staying away from the obvious paths, pushing ideas a bit further, and most importantly, trying to connect with their personal experiences on a deeper level.

Choose a story to explore through artistic practice.

Envision what violence is, through colors, textures, objects.

- Photograph textures, colors, and objects that speak about violence to students. Why them, what do they have in common?

Plan for final art pieces

- Choose media, prepare materials, work on a timeline for completion, and set details for execution.

- Assign or delegate roles within groups for work duties.

Work on artwork as groups, with classroom critiques incorporated.

- Every other week, students analyze their own and one another’s process, using informal presentations and discussions: How is it going? What are your goals? How are we going to get there?

Post artwork throughout our community to get other people involved in this dialogue.

Materials + Supplies

Audio recording equipment

Digital Cameras

Journals

Poster board paper

Variety of art supplies, as available

MCA Connections

Coming to the MCA was a very powerful and positive adventure for my students. Thanks to this experience, they were able to widen their vision regarding what art is, how it is produced, and how to explore subjects in non-traditional ways. Thanks to our visit, students realized that in order to explore a topic such as violence, they didn’t have to use literal or explicit images or objects. Rather, non-explicit elements were found to be more powerful. We viewed the Simon Starling exhibition, which inspired us back in the classroom.

Resources

Artists:

Texts and strategies:

- Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed

- Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed and Games for Actors and Non-Actors

Mauricio Pineda

Reilly Elementary

Mauricio Pineda, originally from Ecuador, is an educator with Chicago Public Schools, teaching visual art at Reilly School to Kindergarten through 8th grade students. He has volunteered for Project NIA, illustrating pamphlets, posters, and various works of art, and has participated in panels and art shows supporting the ending of youth incarceration in favor of community-based means of accountability for violence and crime.

Mauricio is an Adjunct Professor for the Peace, Justice, and Conflict studies at DePaul University. Additionally, he is the Arts Liaison and Chair of the Arts Department at Reilly School and serves as the head of the school’s Restorative Practices initiative, trying to find alternatives to the suspension and detention of students. This program has been highly recognized by CPS’s Office of Social Emotional Learning, granting Mauricio the opportunity to present workshops for teachers, community organizations, and a roundtable discussion with Chicago’s Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Chicago’s Chief of Police, and community leaders regarding Restorative Practices in Chicago Public Schools.

Mauricio reflects on his creative process:

Developing the project was an organic experience that evolved after a student shared a personal story with me at the end of 2013-14 school year. This story described the state of internalized violence that my school community and its neighborhood had slowly and silently assimilated, and the way my students were growing up believing that this construction was normal, unchangeable, and furthermore something that was not supposed to be talked about; thus, the conception of this project became neccessary in order to give my students the opportunity to talk openly about how their lives and the lives of their families were affected by violence.

Knowing that Reilly school was growing in the use of Restorative Practices such as Talking Circles and Peer Counseling, I decided that Art could meet with these practices to develop a creative environment of artistic investigation, human connectivity and empathy. Additionally, I realized the need for tools that could help us analyze the state of our reality at a very profound level; hence, I utilized Theatre of the Oppressed and popular education strategies and exercises to help establish a physical, emotional, and analytical connection between my students, their communities and the subject of our investigation.

At this point, I had the central idea and the means to approach it; however, I was still uncertain of what the end result would look like.

Partnering with the MCA through its Teaching Institute was essential to elevate this experience to a more meaningful state; it was the final component to amalgamate this project. In exploring Contemporary Art and Contemporary Art Pedagogy, I was inspired to transform my role in the class from that of a teacher to that of a facilitator. Thanks to my personal experience at the Institute, I concluded that I needed to provide diverse experiences for my students—hence the role of facilitator, so they could have a variety of alternatives to develop their work in a way that was meaningful to them.

In conclusion, the development of the project was mostly given by students’ personal choices and input, after undergoing different experiences where the only struggle was not having more time to explore, with beautiful and insightful pieces of artwork in the end that helped our community to see itself through the lens of my students.