“And that’s when things got a bit weird and wonderful.”

A LETTER TO FUTURE EDUCATORS

By Richard Schreiber

Dear Future Educator,

In an attempt to develop my practice as an art educator heading into the 2019–2020 school year, I decided to apply for a spot in the Teacher Institute program at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. I’d received emails notifying me of the program, following a relationship with the museum, fostered through repeated field trips I’d taken with my students in previous years. Additionally, the program came highly recommended by a few friends of mine who were past participants and also work as art teachers in Chicago Public Schools.

The summer, week-long intensive portion of the program quickly illuminated to me how different my teaching conditions are compared to the majority of others participating in the program. For starters, only one other participant was an elementary level visual arts teacher like myself. Most were middle school or high school grade teachers specializing in a variety of disciplines. It became immediately apparent to me some of the concerns and objectives these teachers had for their students and teaching practice were, in many ways, quite dissimilar to what I experience at my school. This realization made me question whether or not more serious student issues are being concealed at my school and in my classroom, or whether such issues are much more common for students from under-served communities. The answer to that question, like the answer to most complex questions, is nuanced.

Process

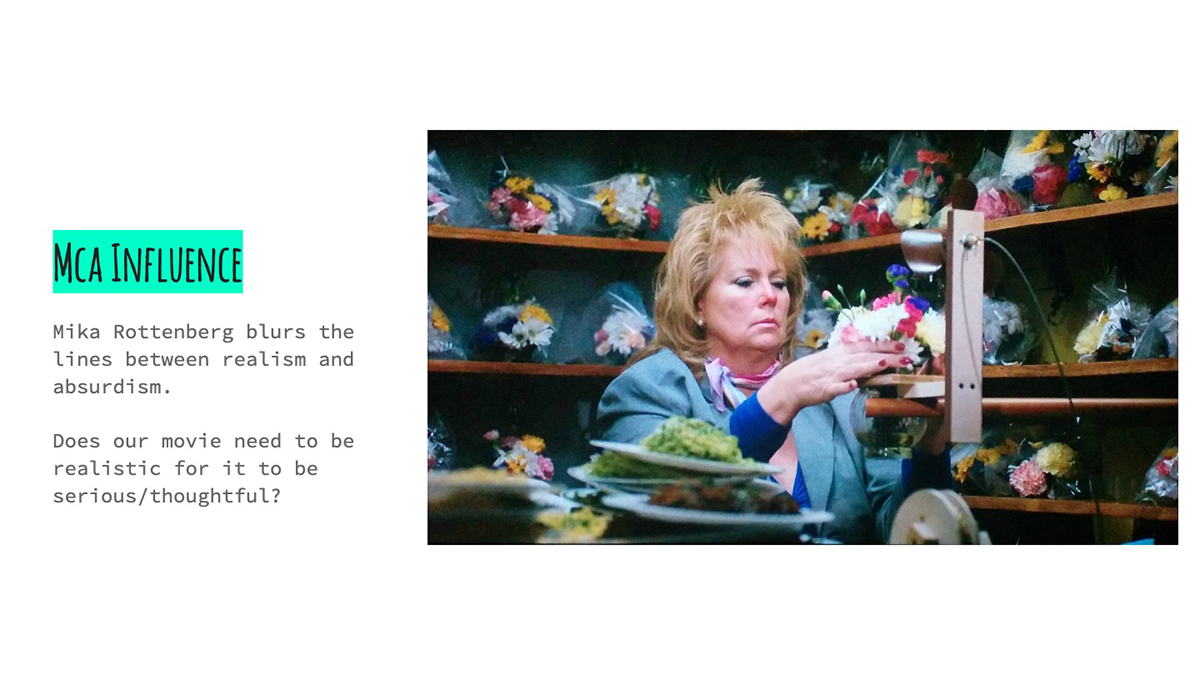

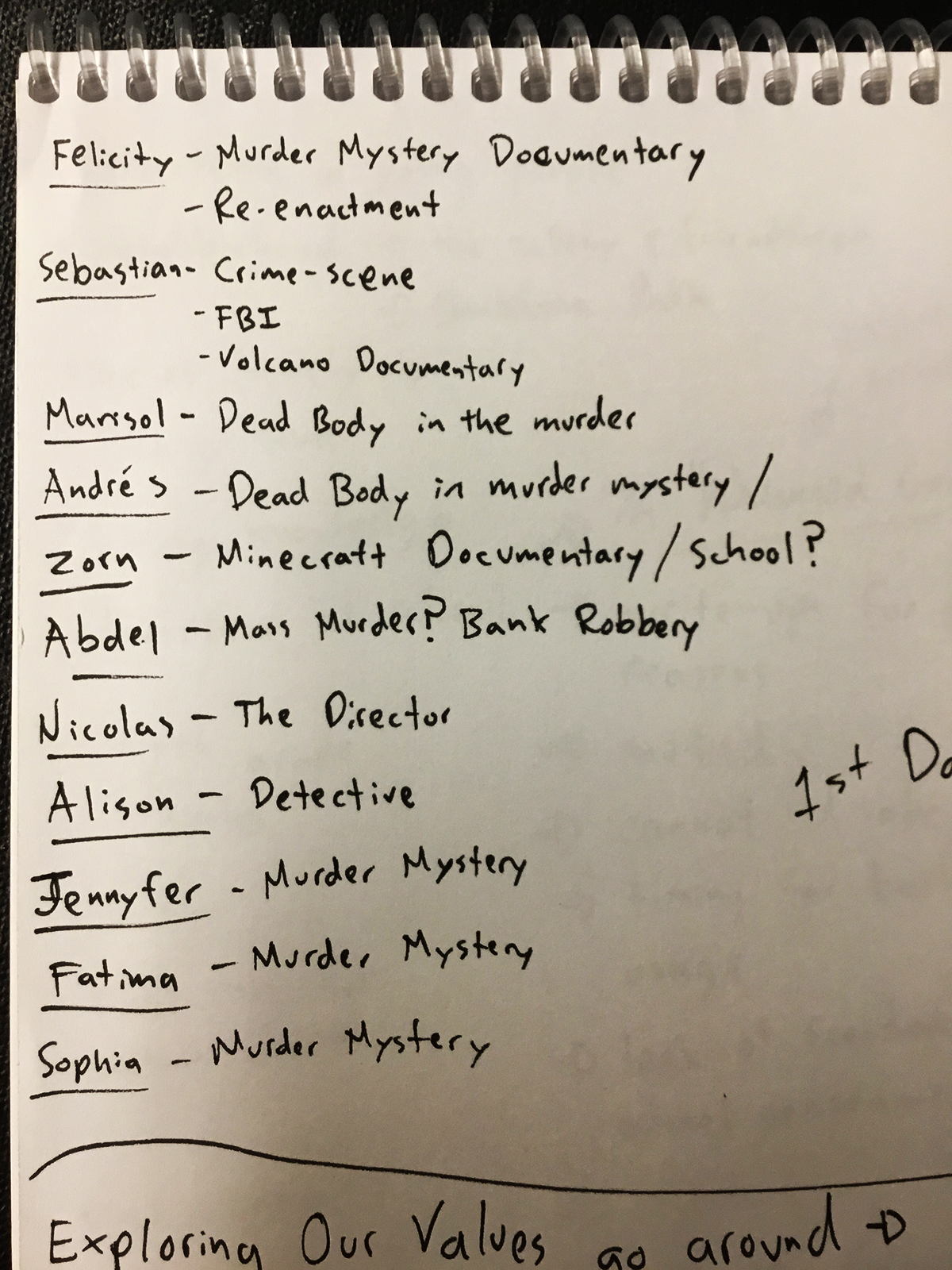

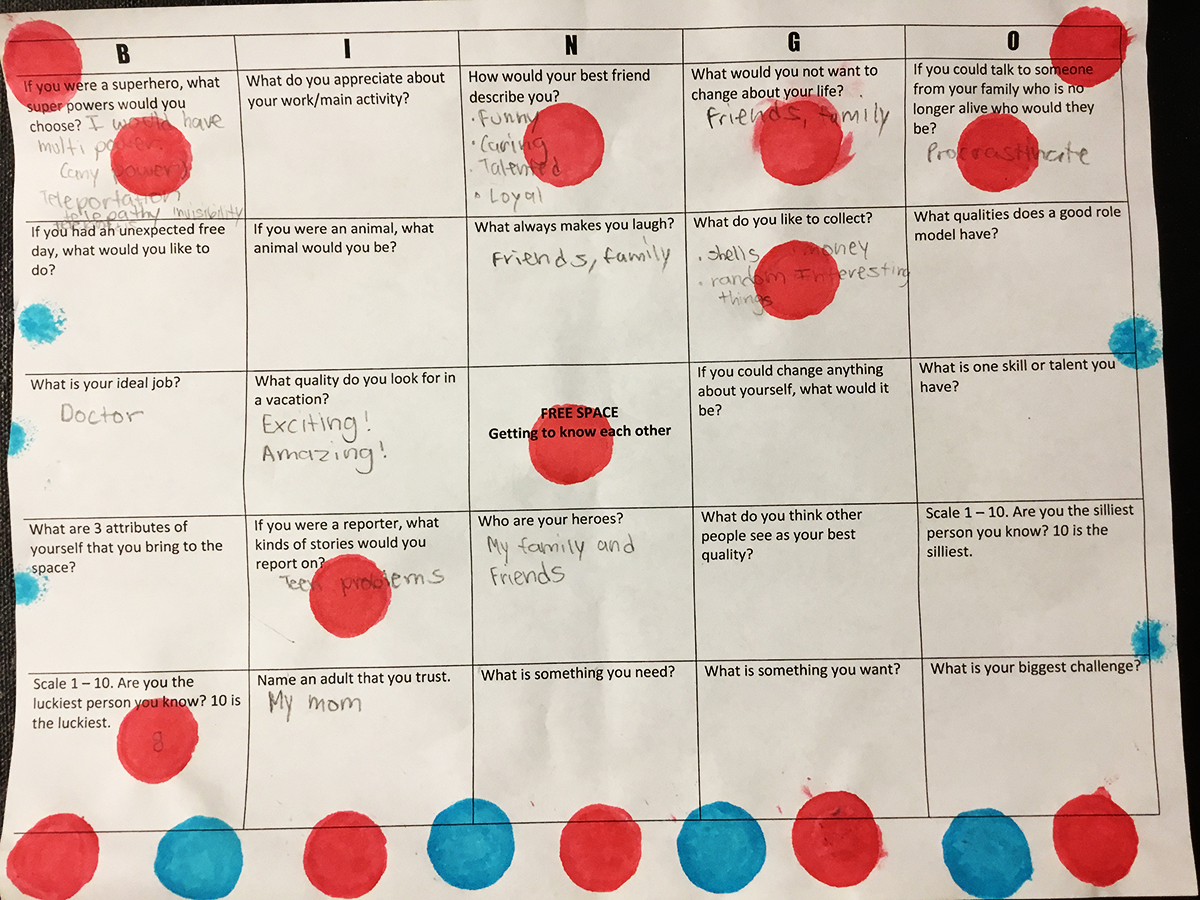

My initial project proposal suggested an attempt at bridging the divide of students separated by our two campuses (elementary: PreK-4 and middle: 5-8), in an effort to create a more cohesive school community and shared identity. Influenced in part by some of the “heavier” and more mature projects proposed by colleagues in the Teacher Institute, I decided instead to carry out the project with an after-school MovieMaker club I organize for 7th and 8th grade students, rather than with the elementary level students whom I see in the classroom daily. I thought this older student cohort would be able to confront more “serious” issues relevant to them and their community. This year’s club rendition became MovieMakers: Documentary Edition, to set the tone for a reality-based objective in our filmmaking.

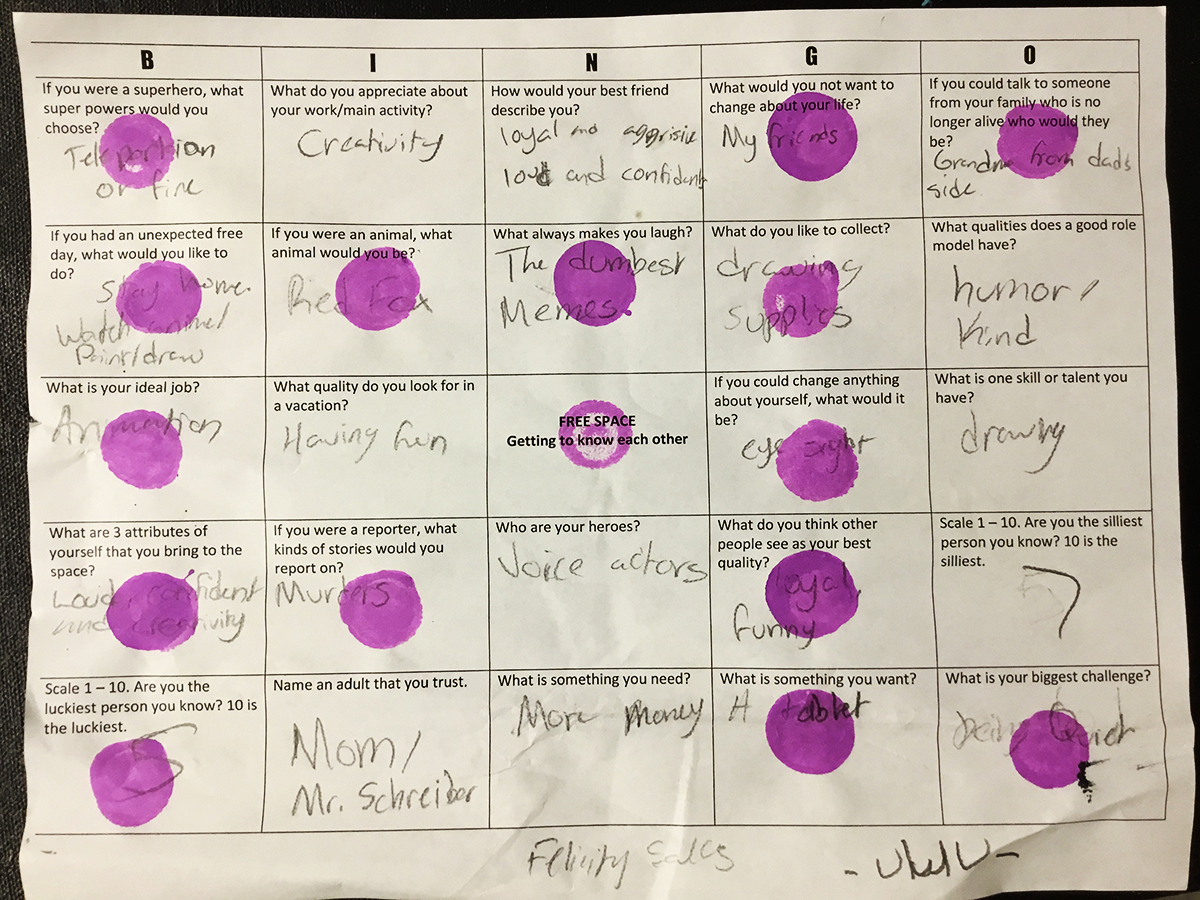

The goal of the project naturally became to create a documentary-style film exploring a topic relevant to club members. It seemed simple in theory: Determine common themes important to each student, decide on one common subject, and develop our film from there. And that’s precisely what we did, more or less, but somehow without the momentum and enthusiasm that had been so fun and infectious throughout the making of our previous year’s film.

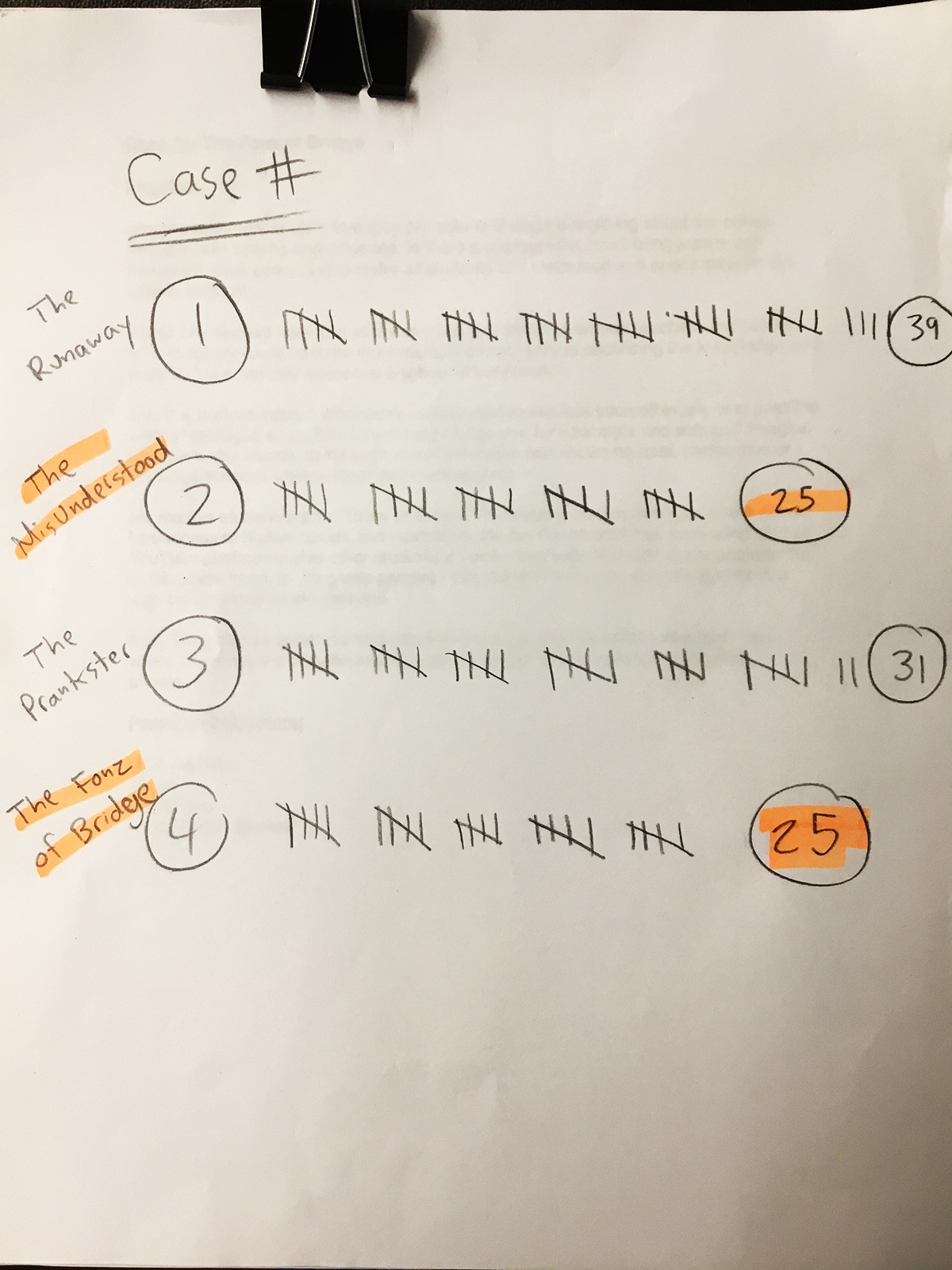

Our initial concept for the fictional documentary, which was voted on from a number of different scenarios I developed based on student requests, involved a student who had the ability to remedy a toxic school community through their Buddha-like nature. The premise was initially titled, “The Fonz of Bridge Elementary,” with a protagonist who, like Arthur Fonzarelli from Happy Days, was a cooler-than-cool character who stood up to bullies and always fought for the underdog. We brainstormed what traits such an individual would possess in a contemporary school environment and began filming scenes (Act 1) of different students’ first impressions of this enigmatic character, whom the club members decided must be a new student at the school in order to have such influence. I believe this requirement by the students for our film’s protagonist to be an outsider to the school community is quite telling. It suggests my MovieMaker students assume change is more likely to come from somewhere else—that, for whatever reason, change from within is too unrealistic.

This idea of whether or not change can come from within is extremely interesting to me, and I find it relevant across many avenues of life. As a fan of sports, it’s emblematic of the trend of firing coaches and managers after a string of losses. On a geopolitical level, it makes me think of authoritarian regimes and climate change and the real/perceived agency of the people under these forces to enact change. Do students have the agency to enact change? Do students believe they have agency to enact change? Are students waiting for somebody else to enact change?

After several weeks of shooting scenes based around our outsider-student-change-agent, it was apparent that my students weren’t fully invested in the concept and the premise felt both dull and abstract. As a voluntary after-school program, the students increasingly appeared to be carrying out an assignment, rather than creating a project in which they had real emotional investment. I needed to reevaluate my intentions with the project. First and foremost, I needed to engage the students and generate interest in the project that would then translate into increased motivation and a sense of ownership.

There seemed almost to be a semblance of resentment or mistrust over our Fonzie-like protagonist – a sort of “who’s this person coming in here and acting as savior of our school” type of sentiment. I didn’t realize it initially, but in hindsight I see that it was quite apparent. For us to imagine a character that could come in and be the solution to all things wrong with our school was to write off our own students’ ability to do this themselves. They wanted to be the heroes in their own movie; they didn’t want to develop a fictional character to play the role.

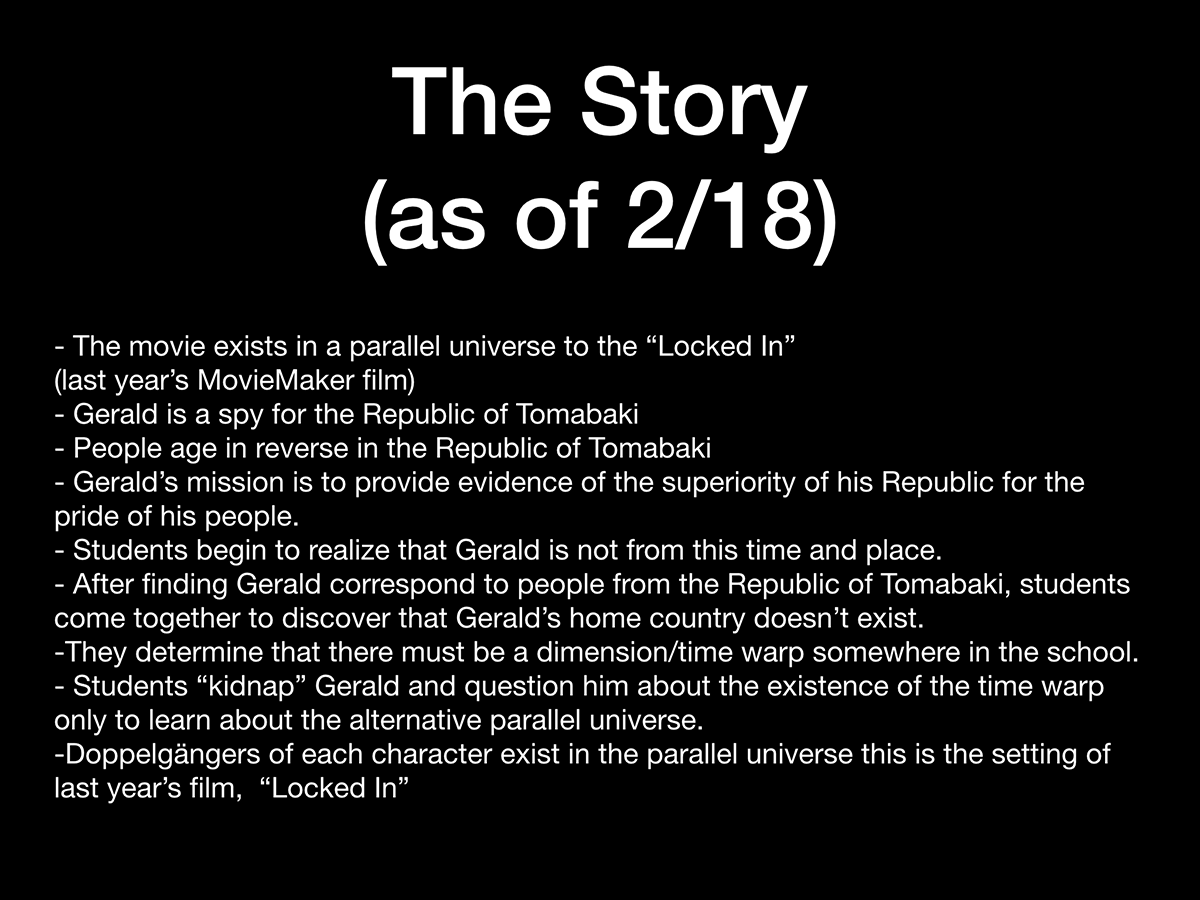

And that’s when things started to get a bit weird and wonderful. Together, we confronted the fact that the movie was feeling a bit dull and cliché and decided to make our Fonzie character, named Gerald, the antagonist of the film. Rather than an altruistic outsider who would change the school through cool and benevolent behavior, a student suggested we instead make him a spy from a fictional, foreign country. Someone else then shared it’d be interesting if this spy came from a country in which all people have the “Benjamin Button disease” that causes people to age in reverse. This brought up a series of fun, hypothetical questions of how a 70-something year-old individual from a (unanimously) communist country would act in a contemporary American middle school setting. So, for Act 2 of our movie, we created scenes in which the same characters featured in Act 1 start to become suspicious of Gerald, as he shows signs of being from a very different time and place. Immediately following these changes in creative direction, students showed more interest in the filming and the creative process. MovieMakers became fun once more.

Conclusion

We have plans for what Act 3 might involve, as things only get stranger and more convoluted in the story we’re telling. Many of the club members want to tie in this year’s film with our “Locked In” film from last year (which, fittingly, also included a time-distortion element). Much like the Marvel and DC movies club participants are fans of, students want our film to tell a story full of fantastical concepts and multiple universes. It’s not at all the type of storytelling I’m used to telling, but through their enthusiasm, I find myself energized by the prospect of making a lighthearted and absurd film with them. We may not be producing a film directly confronting pressing issues in our school community, but the creative process has certainly been in the hands of the students and, for that reason, I feel confident about the integrity and value of our film.

I’d like to think that if I had the opportunity to join a MovieMaker club when I was in junior high that I would have done so. I can only imagine what kind of movie I would have been compelled to create if given any form of creative control over the film-making process. I hope I have allowed, and will continue to allow, space for my students to exhibit their own creative control because, ultimately, creative control is closely related to agency: it is the ability to hold influence in matters that extend beyond yourself. It is the feeling that you have the ability to make a difference, whether that be in the trajectory of a film or the culture of a school.

—Richard

CHANGE IT UP

When things become stale or boring, take a step back and discuss the work you’re creating together. Reintroduce opportunities for creative changes. Consider not only reinvigorating the work with a new attitude, but also subverting or sabotaging problematic elements in the second act.

Richard Schreiber

Norman A. Bridge Elementary School

Richard Schreiber had an unlikely path in becoming a PreK-4 Visual Arts teacher. Though his Northern Californian childhood included a mother and two older siblings who went on to earn Fine Arts degrees, he himself took just one Arts course in high school before studying Economics and Creative Writing at Santa Clara University. Following graduation, Richard moved to Vietnam for two years to teach ESL at a college on the outskirts of Ho Chi Minh City, until eventually moving to Chicago to attend the School of the Art Institute's masters program for Writing. After one unmotivated semester Richard transferred into the Masters of Arts in Teaching program offered at SAIC, unknowing that his degree would only qualify him for jobs Arts-related teaching positions in years to follow. Fortunately, the program proved spectacular and, although it has taken some time for Mr. Schreiber to convince himself he's passionate enough about Visual Arts to make a career out of teaching it to young people, he's currently quite content in his position at CPS' Bridge Elementary School on the far, northwest side of Chicago. Having spent four years as the school's 5–8th grade Art teacher, Richard moved to the elementary level two years back due to cutbacks in the Arts at his school. Outside of the classroom, Richard spends the bulk of his time, biking, playing soccer, singing karaoke, studying German, listening to professional wrestling podcasts, and lounging about his lovely Lincoln Square condo with wife, Anna, and cats, Bob and Barbara.